Autumn 2021

A ground-breaking survey

A History of Arab Graphic Design

By Bahia Shehab and Haytham Nawar. Designed by Sharah Shebl and Ahmed Helmy. AUC Press, 2020, £39.95, $49.95

As educators of visual communication in the Arab world, we are all too often guilty of slipping into a Eurocentric design pedagogy, partly because our study programmes are built on these principles and partly because of a complete lacuna in terms of ‘other’ references. The ‘other’ in this case refers to our own visual references. The lacuna stems from our own shortcomings – regarding ‘Arab’ design as an archaic, traditional and even religious art form.

A History of Arab Graphic Design is the first reference to provide a holistic overview of the history of graphic image production in the Arab world. It takes the reader on a one hundred-year journey from the debut of the Arabic printing press to late twentieth-century designers.

With unrelenting determination, two authors have come along to prove that Arab graphic design does exist and build this long-awaited history of the subject. For four years, Bahia Shehab and Haytham Nawar, art historians and professors at the American University in Cairo, built an archive of graphic work from a multitude of sources. They did so against a non-existent culture of archiving and preservation. They accessed a considerable portion of the work by travelling across war-torn countries (some of which banned them from entering), collecting material that was often reluctantly and suspiciously shared, interviewing the designers by hearing their stories through the vestiges of conflict and political turmoil, contextualising these stories within the turbulent histories of the region, and documenting their findings into this invaluable volume.

The 384-page book includes 25 per cent of the material the authors discovered. It is an anthology that surveys around 80 designers over a period from the late nineteenth into the twentieth century. The authors attempt to place the designers’ work in context, explaining the political and social atmosphere, their circle of friends, their tutors and their tutors’ tutors, the kind of collectives that were forming at the time, and the reasons for producing the kind of work they did. The reader gets a comprehensive and panoramic view of what it was like to design at different periods, the technologies used, the types of commission and the clients behind them. The driving force behind much of the commissioned work was political. The authors keep a critical lens focused on the Arab world throughout.

Built on a linear timeline, the chapters cover periods of ten and twenty years under themes that draw on broader historical and visual contexts. The book embarks on a very concise overview of the Islamic arts, with Arabic calligraphy as its main proponent to ‘create a link in the minds of the readers to the visual history of a region that is often ignored and elided from history books’ as the authors claim. The second chapter looks at how the foundation of art education in the Arab world produced artists and calligraphers who were dubbed as early designers.

Under the theme of design for the masses, the third chapter explores the rise of newspaper and magazine publishing, such as the development of the Arabic typewriter, and concludes with a glimpse into the booming Egyptian film poster design scene. Spearheaded by Lebanese intellectuals, who found in Cairo a cultural haven and the economic viability for publishing new political ideas and religious interpretations, an emerging cultural movement defied colonial rule in multiple ways.

The fourth chapter sets the scene in the 1940s and 50s for emerging pioneers of Arab modern design in search of visual cues that identify their presence, most prominently Abd al-Salam al-Sherif and Hussein Bicar’s design and illustration for children’s magazine Sindibad.

In the shadow of their colonised history, newly independent Arab states forged a revival of nationalist ideals, some local and some more pan-Arab. The reader is also taken on an anecdotal trip to the Sudanese design school that hatched the first official Arabic type design school, including the influence it left on the Letterist movement.

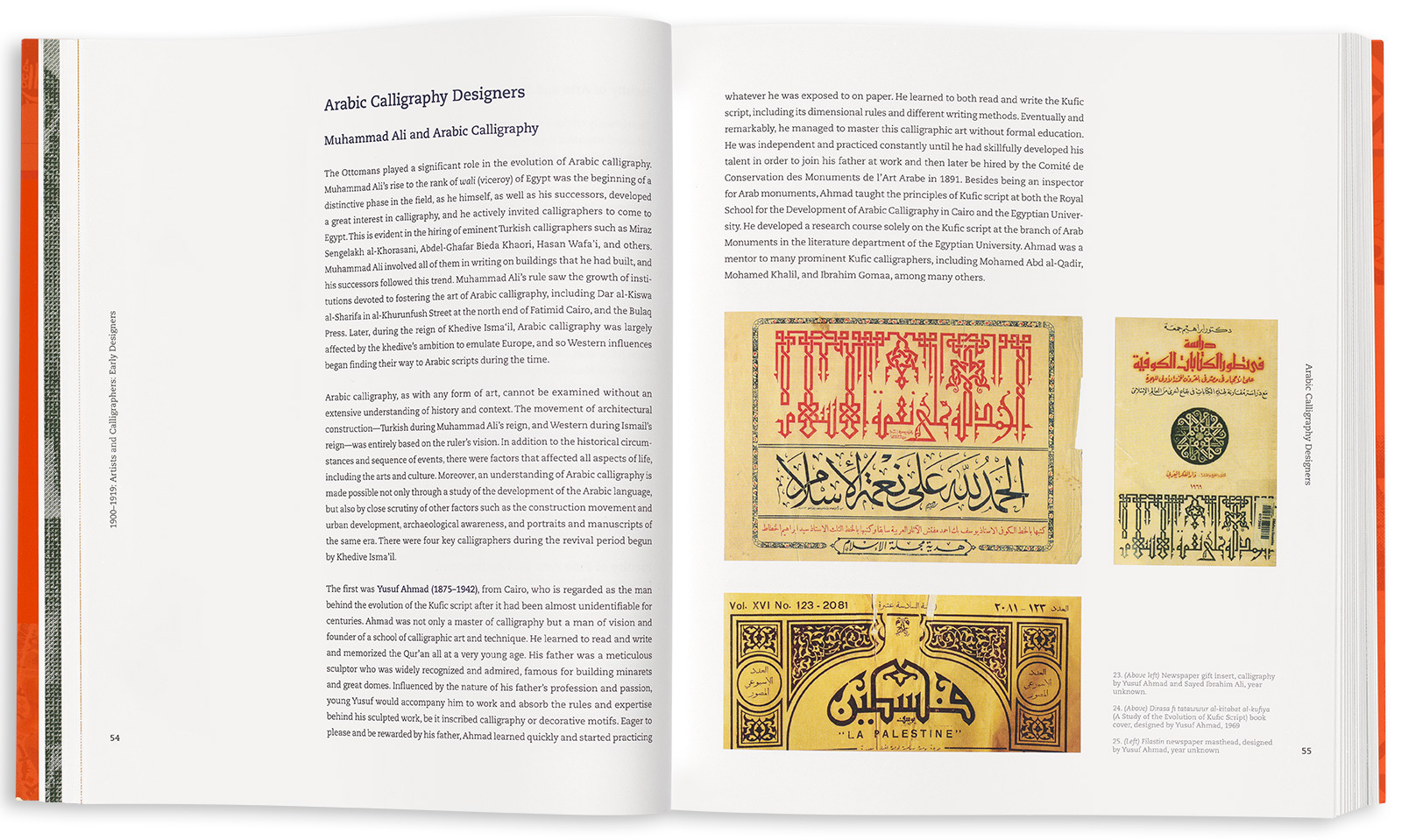

‘Long Live the Unity of Struggle Shared by the Palestinian People and the Peoples of the Soviet Union’, a 1985 poster by Egyptian designer Hilmi al-Touni (b. 1934), shown in A History of Arab Graphic Design. Top. Spread from A History of Arab Graphic Design covering Arabic artists and calligraphers from the early 1900s, with newspaper clippings and book covers in Kufic script by Yusuf Ahmad and Sayed Ibrahim.

The power of the resistance poster in the Palestinian struggle is the main subject of the fifth chapter, with the ‘existential need of the oppressed to be heard’. The protagonists, such as Ismail Shammout, Vladimir Tamari and Burhan Karkutli were part and parcel of the Palestinian resistance who capitalised on their skills to advance the ideologies they were affiliated to. The sixth and seventh chapters shed light on the most important Arab designers who have either fled from political instability and persecution within their home nations or have oscillated between living at home and seeking refuge abroad. Lebanese artist Mouna Bassili Sehnaoui is one of the four female designers featured in the book whose work for the Lebanese government is still in use today. The reader encounters some tragic accounts of persecution: from Iraqi Nadhim Ramzi, who was arrested for designing a progressive typeface that visually mimicked Hebrew; and Mohammad Said Al-Sakkar, whose type design forced him to flee Iraq; to Youssef Abdelké, who faced house arrest in Syria following the start of the war in 2011.

These chapters highlight the works of Burhan Karkutli, Hilmi al-Touni, Abdulkader Arnaout, Dia al-Azzawi, Mohieddine al-Labbad, Kamal Boullata, named as third-generation designers, and Kameel Hawa, Youssef Abdelké, Emile Menhem and Munir al-Sha‘rani, the fourth generation.

The eighth and final chapter largely covers Lebanese postwar design and the ‘rebirth’ of the education scene. Through their design and education practices, Leila Musfi and John Kortbaoui paved the way for a fresh wave of graphic design graduates who were encouraged to embrace and experiment with their own visual culture to counter the fast-crawling tentacles of the commercialised and globalised advertising world. Designers soon forged an organic relationship with calligraphers, using the Arabic script as a proponent of local identity.

Throughout the book, the reader discerns an underlying bias towards the Egyptian design scene – perhaps understandably so because of the authors’ nationality and the readily available broad range of resources within their reach. The reader also occasionally misses seeing artwork that the text details at length. In other instances, reproductions of artworks could have been larger or of better quality; the authors express the difficulties they encountered in collecting some of the artwork from archives that have been neglected, partially destroyed or have gained a detrimental patina of age.

By taking a sweeping overview of the featured artworks, the reader can discern the changing landscape of visual culture where a distinct visual vocabulary starts to slowly emerge for each period (producing its own generative and shifting aesthetic), and where pan-Arab nationalism brushes up against Western Modernism. Moreover, this historic overview ‘professionalises’ the field of graphic design in the Arab world, a claim that has been rejected in the last decades for several reasons.

Cover of Al-Musawwar magazine, issue no. 1680 from 1956.

For one, the informally trained designers producing the work were activists, freedom fighters, writers, artists, typesetters, illustrators and calligraphers. They did not gain the term ‘graphic designer’ until the early 1990s with the development of a formal graphic design curriculum. Secondly, the general perception that disparaged the design of print as a ‘commercial’ level of artistry when compared to the revered Islamic arts, most prominently the calligraphic arts, inherently slackened the specialisation of the profession. With this book, Arab graphic designers, students and researchers should be able to reclaim their history and, in doing so, move forward.

A History of Arab Graphic Design will surely engage students and scholars from various disciplines including (but not limited to) graphic design, visual culture, art history and political science, as well the general reader interested in learning about the emerging aesthetics in times of peace, conflict and political unrest across the Arab world. (Readers will be eagerly awaiting the Arabic version). The book leaves the doors wide open for future scholars and researchers to provide a cohesive and deeper theoretical framework for the work and the designers featured thus far. It also opens space for students of graphic design in the Arab region to have role models and a standard of excellence, adding integrity to their profession while grounding and contextualising the work they will create. Finally, it provides a visual repertoire and a point of departure from the exclusivity of Western design. It is high time that Arab visual and verbal language took centre stage in building an active cultural practice shared by everyone.

Cover of A History of Arab Graphic Design.

Yara Khoury Nammour, assistant professor, American University of Beirut

First published in Eye no. 102 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.