Autumn 2023

Banquet for a dude

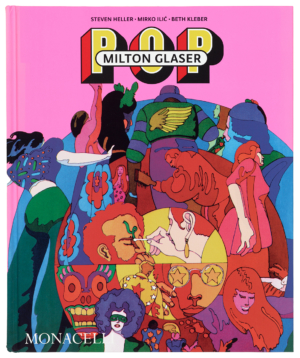

Milton Glaser: Pop

By Steven Heller, Mirko Ilić and Beth Kleber Designed by Mirko Ilić Corp. Monacelli Press, £44.95

The late Milton Glaser occupies a unique position at the pinnacle of Anglo-American graphic design. While other members of the field’s pantheon are renowned for their typographic brilliance and their command of purely graphic form, often rooted in modernist sources, Glaser was a pictorial image-maker whose designs were constructed from and around the drawings he made in a prodigious variety of styles. He was a consummate illustrator, but the force of his presence within graphic design is such that we tend not to think of him that way. Although it may be hard to credit now, there was a moment in the late 1980s when this commitment to drawing led his achievement to be undervalued. ‘Graphic Design in America’, one of the most ambitious survey exhibitions about the subject ever mounted (see Reviews, Eye 1), largely excluded him for being insufficiently modernist. Glaser, until then celebrated as one of the greats, was understandably upset.

Aside from that regrettable blip, Glaser has been well served by international exhibitions, two self-initiated monographs, books devoted to his drawings and posters, and an unmissable survey of The Push Pin Graphic, the superbly inventive periodical he created with his studio partner, Seymour Chwast, an equally gifted graphic artist. Milton Glaser: Pop, completed since his death by a team of close colleagues – writer Steven Heller, designer Mirko Ilić and Glaser archivist Beth Kleber – is a design book of the year in terms of its visual content alone. More than 1000 images from the late 1950s through the 1970s, many unpublished in earlier books, provide a sharper sense than ever of Glaser’s virtuosity, range and accomplishment in these years.

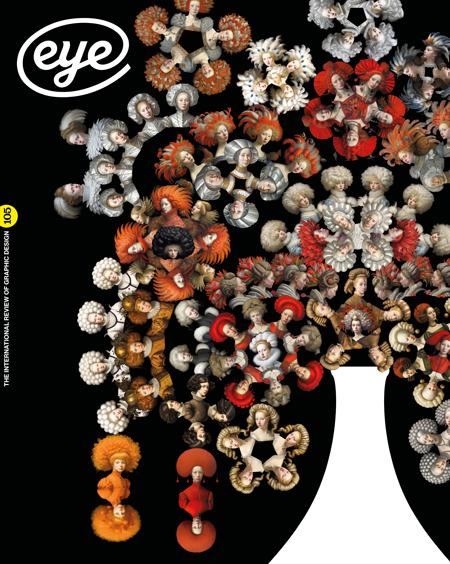

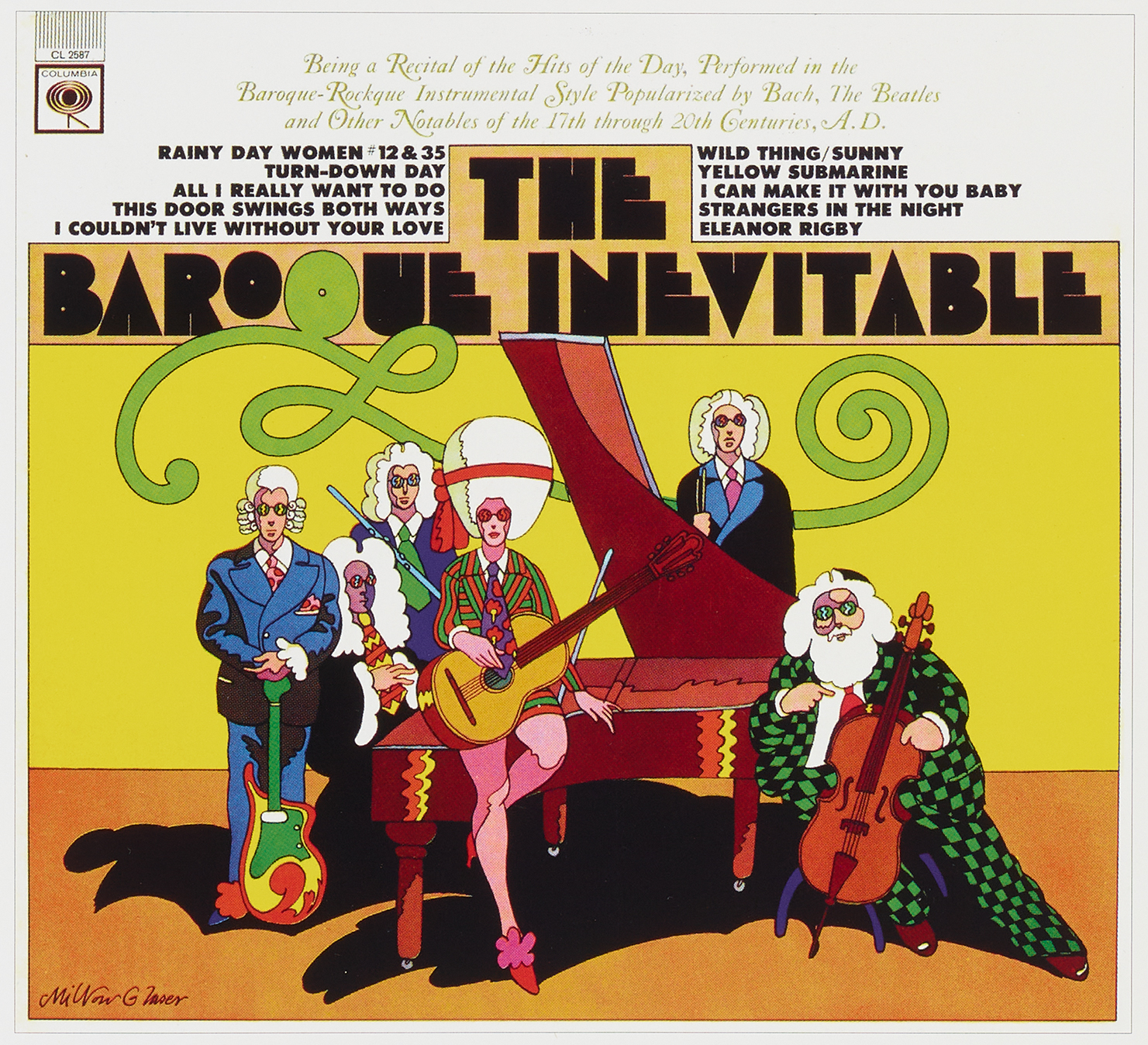

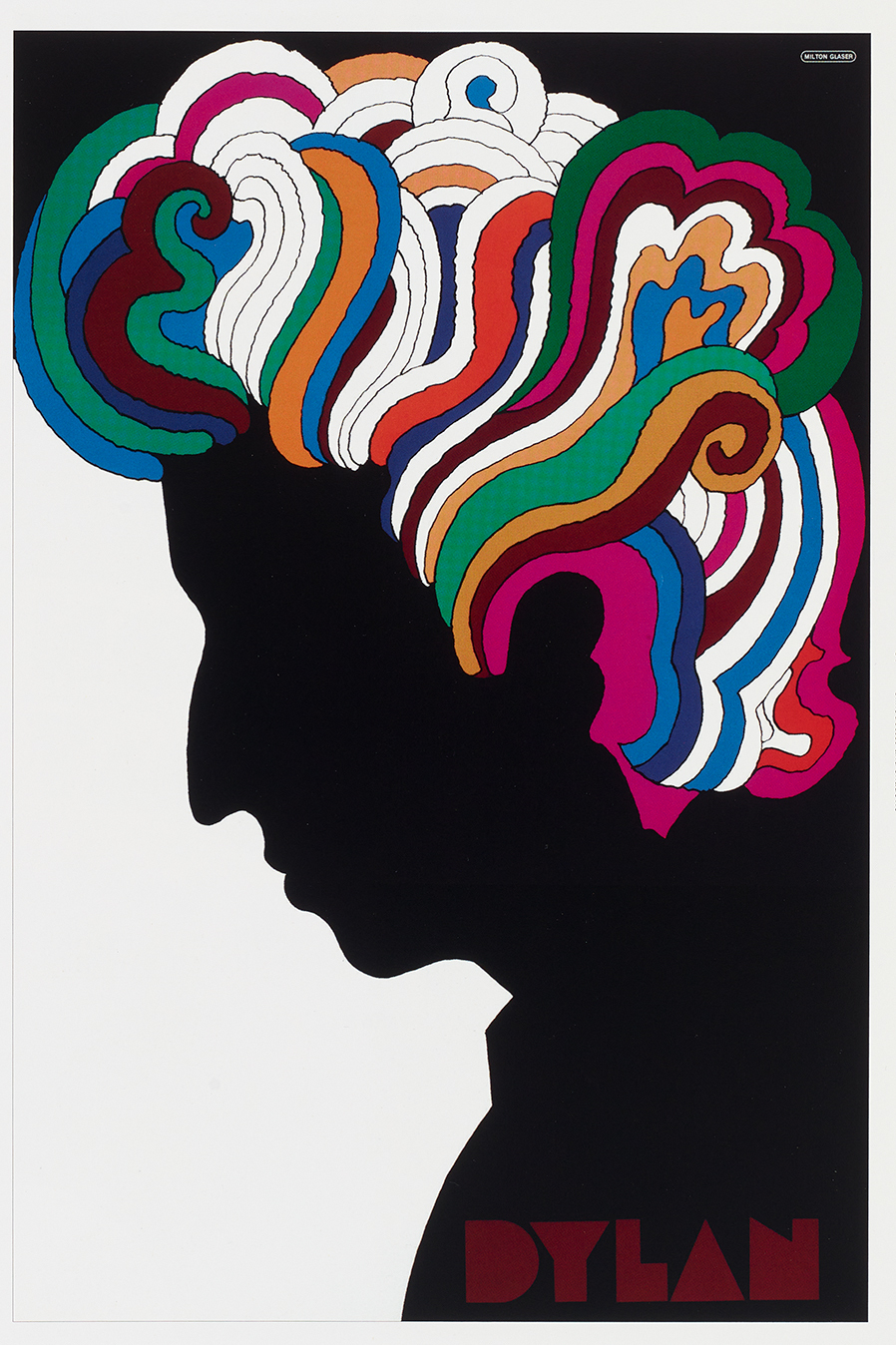

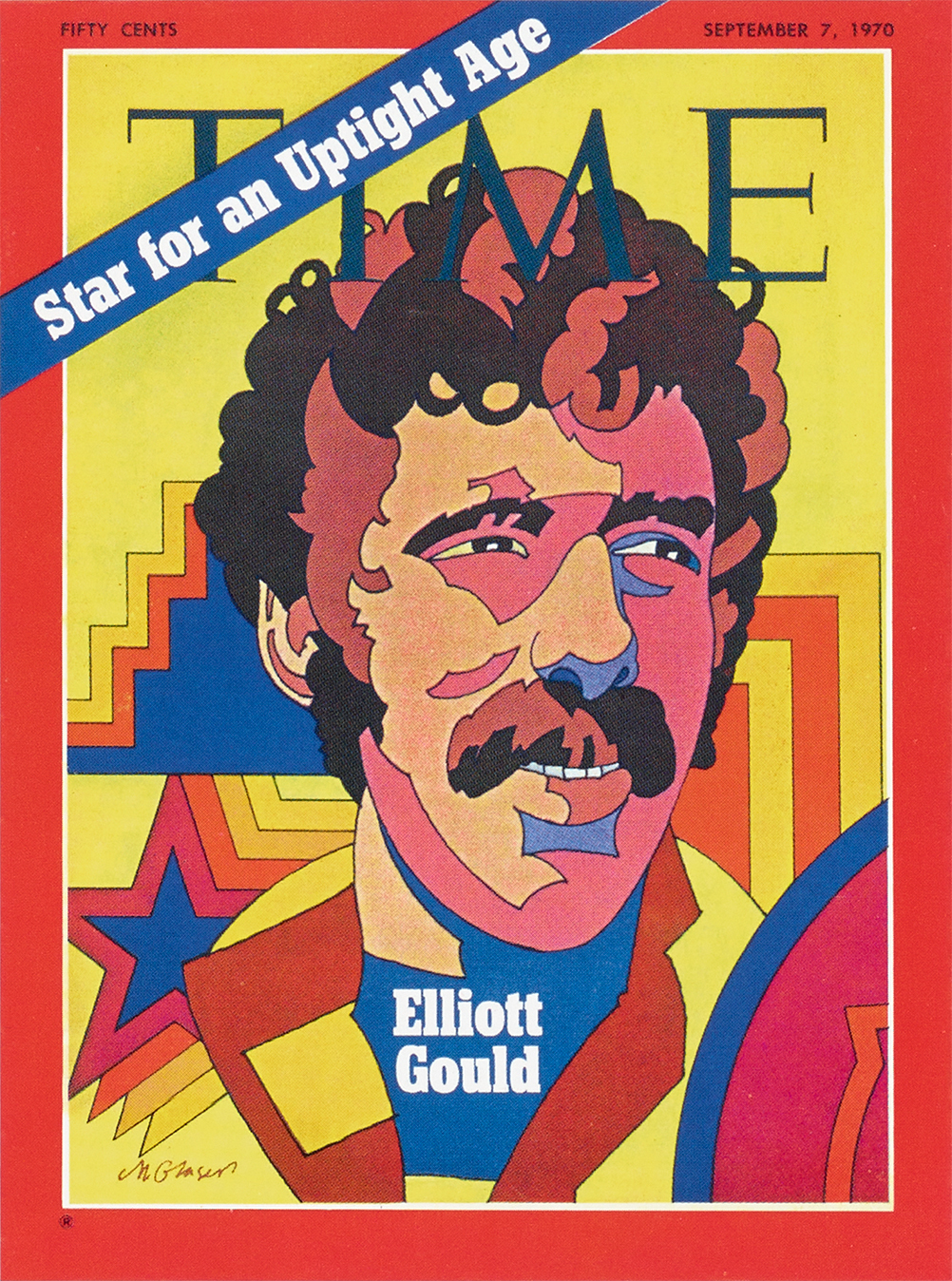

The decision to organise this work under the banner of ‘Pop’ gives the book a compelling premise fully expressed in the high-impact cover, which unites Glaser’s Baby Fat typeface (ca. 1966) with an illustration used on Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), long regarded as a classic of the freewheeling, subjective ‘new journalism’. Glaser’s carnivalesque montage of wild hair, masks, face painting and music immediately locates him – as an artist – at the swirling psychedelic centre of the era. The book has many images like this, from The Baroque Inevitable album cover – baroquely styled hippie dudes! – for Columbia Records in 1966 to a Time magazine cover about California three years later, which the introduction chastises in passing as ‘excessively stylized’ and ‘trope-ridden’. (Tell us more.) There are no doubts, though, about Glaser’s rendering of Bob Dylan as a rainbow-tressed silhouette, a poster image that can be justly labelled an icon.

Glaser’s poster for Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits, Columbia Records, 1967. Art director: Bob Cato.

Top. Cover of The Baroque Inevitable (Columbia Records, 1966), illustrated and designed by Milton Glaser.

The book’s title raises three interconnected questions. The first concerns Pop itself. What was Pop art? The subject has been exhaustively covered by art critics and art historians, but to understand the ways in which graphic design might be interpreted as a form of Pop some discussion of Pop art is essential. Richard Hamilton’s famous definition would be a good place to start. Pop art, he said, was popular, transient, expendable, low cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous and big business. However, the book makes only the most cursory reference to Pop’s origins, providing no foundation for the second question: is there such a thing as Pop graphic design and, if the genre exists, what did it borrow from Pop art? Histories of graphic design by Meggs, Eskilson and Hollis don’t identify a Pop graphic style under that name, although everyone addresses psychedelia and postmodernism. More surprisingly, Heller and Chwast’s regularly updated Graphic Style also doesn’t single out Pop as a clearly identifiable and nameable category of graphic design.

The earliest attempt to establish the existence of ‘Pop graphic design’ came in the British design historian Nigel Whiteley’s Pop Design: Modernism to Mod (1987) where he usefully pinpoints three phases with reference to the British design scene: ‘Early Pop’, ‘High Pop’ and ‘Late Pop’. The Beatles’ film Yellow Submarine, with psychedelic linear animations by Heinz Edelmann, is an example of Late Pop. Glaser was irritated that viewers sometimes attributed the film’s graphics to him, though the similarities of style are striking.

More recently, Thomas Crow’s book The Long March of Pop (2014) traced the connections between art, music and design, signalling a productive interdisciplinary direction for future research. Crow discusses work by Glaser and Push Pin and shows a Push Pin Monthly Graphic cover. Glaser’s Dylan poster makes an appearance in Pop Art Design (2013), a Vitra Design Museum catalogue, alongside a comic strip illustration by Guy Peellaert in a style similar to Glaser’s and Edelmann’s. There has been some discussion about who introduced this style into the 1960s context – Glaser’s claims on it go back to 1964 – but the clear graphic line containing blocks of flat colour ultimately derives from comic strips, and Glaser wanted to draw comics in his early days. Hergé’s influential version of the style, seen in his Tintin books, is called ligne claire. It’s worth also noting that the historical investigation of Pop’s graphic dimension continues in Anne Massey and Alex Seago’s essay collection Pop Art and Design (2018). There is ample context for a discussion of Pop graphic design.

Cover of Time magazine, 7 September 1970, designed by Glaser. Art director: Lou Glessman.

The third question we need to ask relates to Glaser. As a commercial artist and designer, what was his view of Pop art, was he consciously attempting to apply aspects of Pop in his design, and if so, why? The introduction presents the issue in the briefest terms as one of commercial opportunism. The emergence of Pop art ‘gave Push Pin a brand-new client base that needed their styles’. But Pop art was a response to this dominant commercial culture of ads, supermarket packaging and images of abundance and celebrity, using them as subject matter because this was the reality of capitalist society. The subjects shown, rather than the styles of representation (which were multiple), were the crucial point and, implicitly or explicitly, Pop art is often critical of its sources. Feeding the surface styles of Pop back into commercial media short circuits any critical dimension. In response, the introduction merely notes blandly that ‘Glaser’s work was not intended as cynical or ironic barbs at commerce or commercialism.’

The book proposes that Glaser was creating an ‘alternative’ mass-produced form of Pop art aimed at a broad audience, rather than gallery-goers and collectors of one-off paintings. But this is to confuse effect and intention. Eloquent as Glaser’s images may be on their own terms, his purpose remains ambiguous – no sources are given for the few quotations and there is no bibliography. What did he say in the 1960s? We are told that Glaser described the linear psychedelic style as ‘paint by numbers’ and was glad to leave it behind. When he reluctantly returned to this manner, decades later, it was to create a poster for Mad Men’s final season. According to the authors, it was the high fee that persuaded him.

Milton Glaser: Pop is a banquet of a book and an enormous pleasure to peruse. It contains many superlative images that aren’t obviously Pop, especially from the earlier years – for instance, book covers where the illustrational style is closer to expressionism at a time when Abstract Expressionism was recent history. If the authors see these images as Pop (or proto- Pop) for some reason, then they needed to make the case. Glaser’s huge and protean body of work – ‘Art is work’, he said – provides an opportunity to enlarge our understanding of what Pop graphic design was, with implications for remapping the wider context of design and illustration in those years. A scholarly reappraisal of Glaser’s oeuvre is now pressing.

Cover of Milton Glaser: Pop.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, professor of design and visual culture, University of Reading

First published in Eye no. 105 vol. 27, 2023

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.