Autumn 2023

Graphic friction

The Graphic Language of Neville Brody/3

Texts by Adrian Shaughnessy, Neville Brody, Steven Heller, Jo-Ann Furniss, Naomi Hirabayashi. Editors: Shaughnessy and Brody. Design: Brody Associates. Thames & Hudson, £50

For the late 1980s / early 90s graphic designer, the two volumes of The Graphic Language of Neville Brody were must-have items on the studio bookshelf, key reference points in establishing your creative credentials. That the books became such symbols, when Brody and collaborator Jon Wozencroft had set a far more intellectual agenda in the texts that accompanied the visuals, echoed the way Brody’s intelligent designs for The Face magazine had quickly become an easy addition to a thousand yuppie mood boards.

The original designs and their instant re-presentation in book form worked at these multiple levels, propelling Brody forward as the poster boy for graphic design. Volume one accompanied a large exhibition at the V&A Museum in 1988; he appeared on the cover of Blueprint the same year. Had any graphic designer ever received such attention?

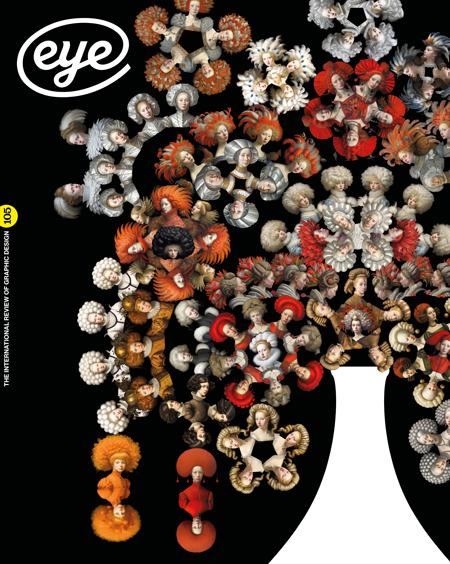

Cover sets the bold tone of The Graphic Language of Neville Brody / 3.

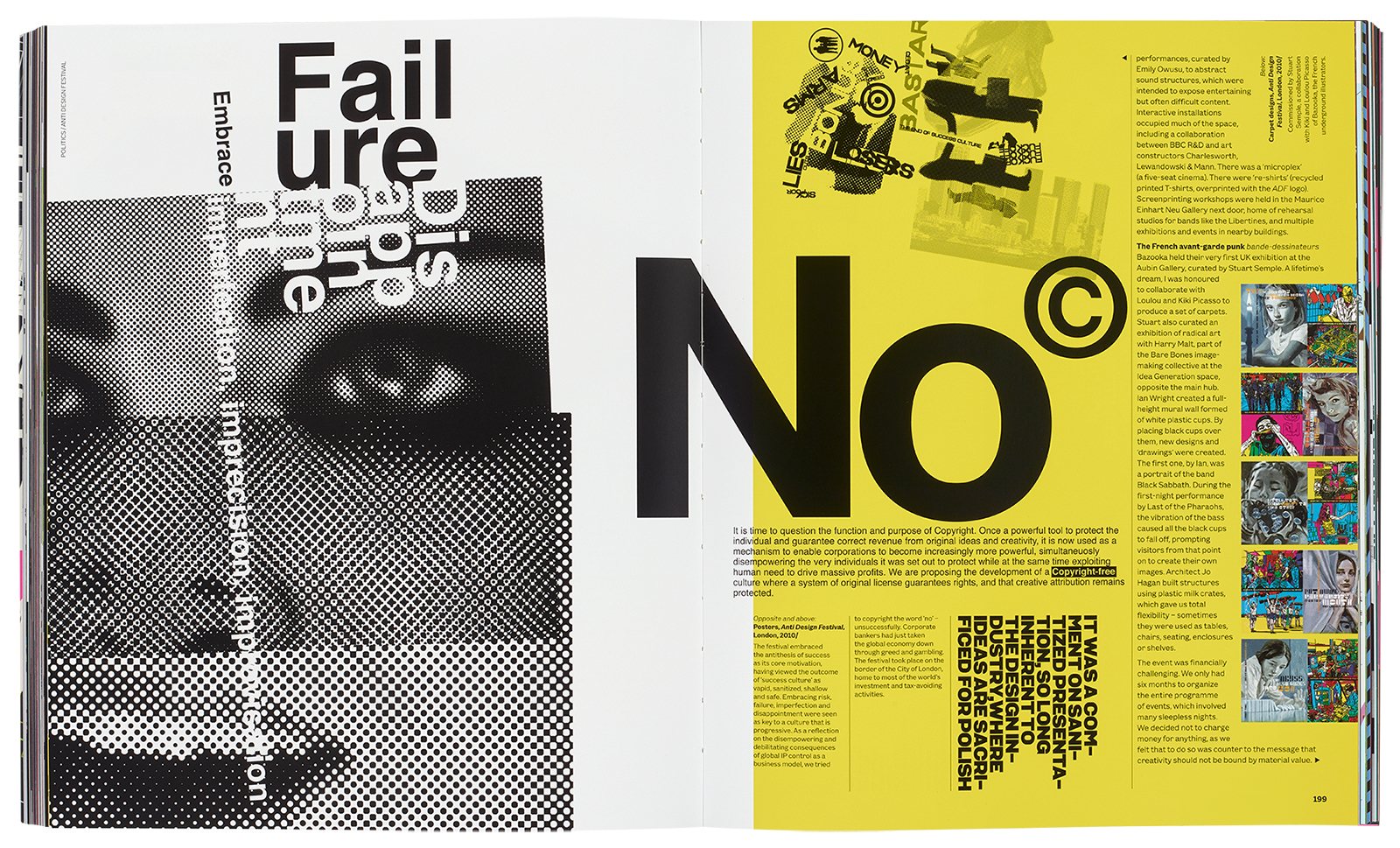

Top. Spread collaging posters for the Anti Design Festival (2010). The design expresses the emotion of the event itself rather than show a series of its posters.

Brody’s fiercely independent approach to the industry was born of the post-punk era. He never gave up his independence, and has continued to lead his own studio, allowing him to combine working for the likes of The Times, Channel 4 and Samsung with campaigning for the soul of visual design – reinventing the Visual Communication MA course at the Royal College of Art, taking charge at D&AD, and organising the ‘Anti Design Festival’ (2010) as an alternative to the ‘London Design Festival’.

The arrival of a third volume of The Graphic Language of Neville Brody this summer maps the 30 years since volume two. It is a fabulous book. At 352 pages, it is significantly heftier than the first two. Packed with text and image, it avoids the preciousness of most design monographs. It emphasises the central role that production technology has always played in his work. His early designs for Fetish records made a feature of coarse halftone dots, and a rare image of him at work in The Face office shows him creating bespoke headlines with pen on graph paper.

His books have also reflected these technological changes. The first was produced using traditional cut and paste artwork, the second used an early version of QuarkXPress, and the new one makes full use of Adobe Creative Cloud – there is barely any white space here (although it is also worth noting that Brody maintains an ancient Apple Mac in his studio specifically to run his preferred Freehand graphics programme).

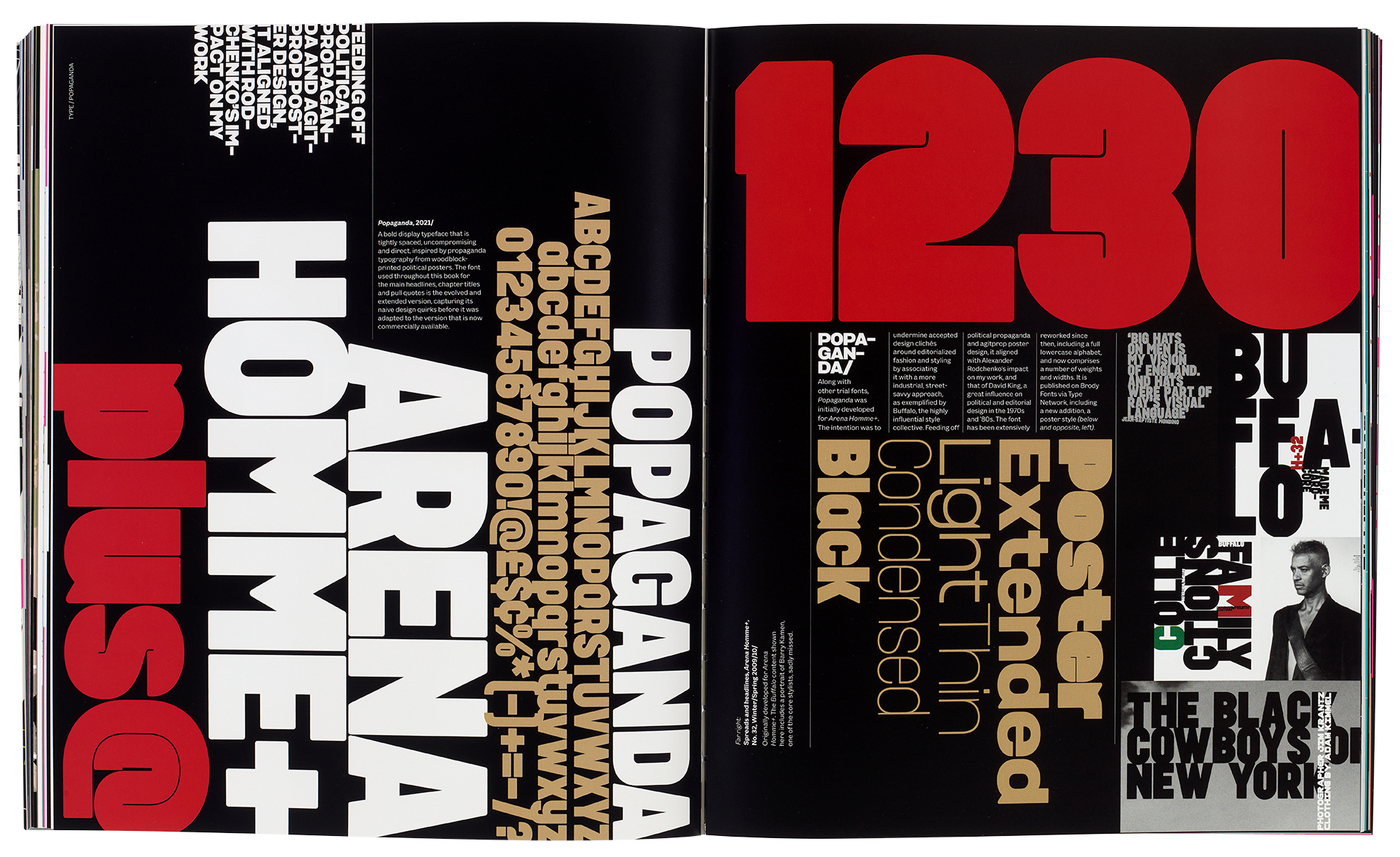

Splitting the content into themed sections (Protest / Protect / Disrupt, Typo / graphism, etc.) breaks up any sense of chronology, and together with a brief opening section backtracking through work from the first two books, makes clear how Brody’s approach has matured without losing its essential Brody-ness. Common visual themes – bold Modernist typography, brushstrokes, graphic icons – recur, whether the work is for Coca-Cola, the England football team, or The Face.

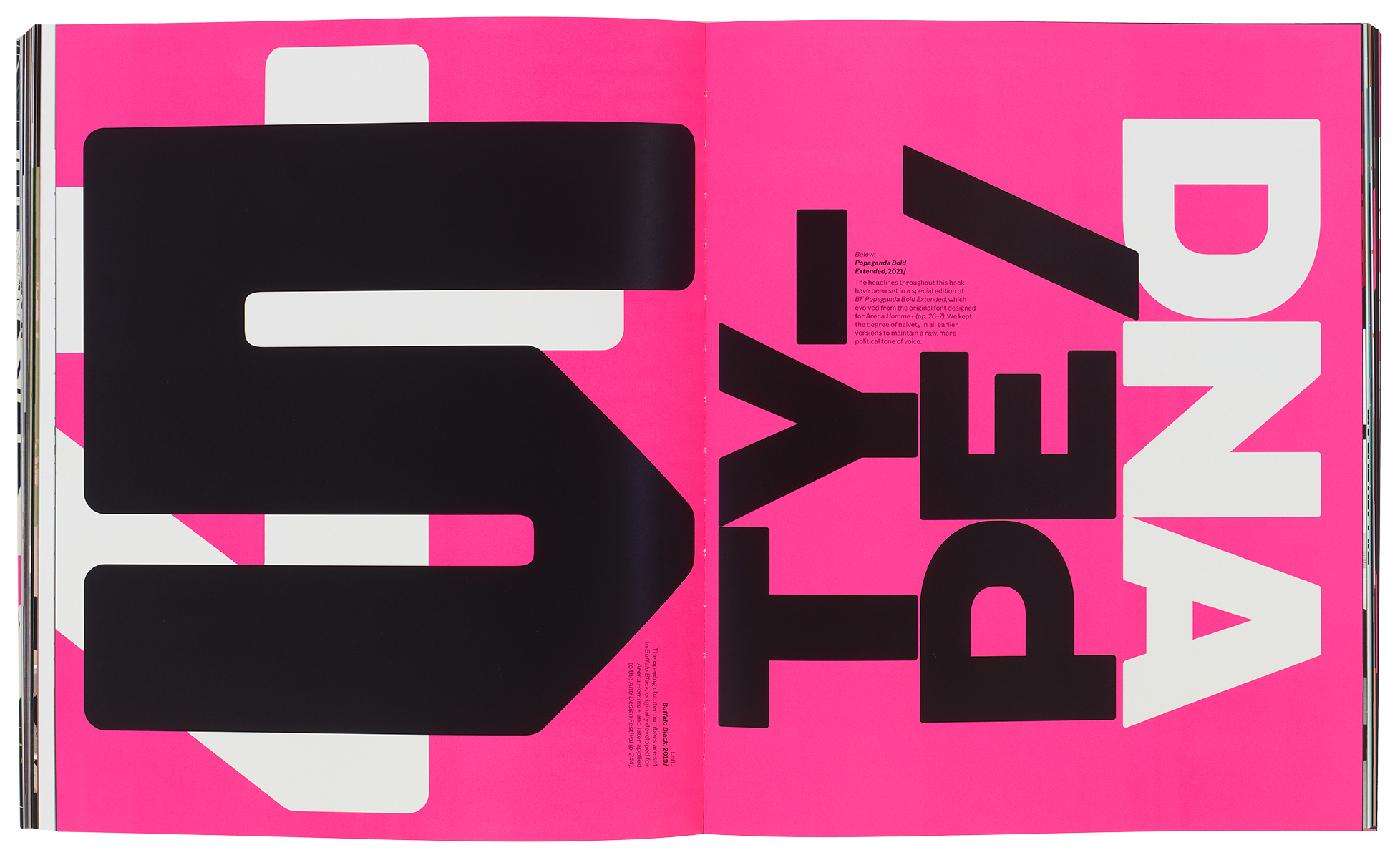

The book contains a huge body of work smashing the most out of three base elements: type, image and colour, which at times blur into single entities. These elements are the starting point for all graphic design of course, but Brody pushes their interaction to the edge of legibility. At last the ‘graphic language’ of the book series’ title is present on the page.

One of the section dividers from The Graphic Language of Neville Brody.

It is no surprise to find an entire section of the new book dedicated to the twenty issues of Brody’s experimental type publication Fuse. Launched in the 1990s alongside a conference series, Fuse was ahead of its time. It still looks so now. Packaged in a slim card box, each issue contained a floppy disc of experimental fonts by various designers, and a set of posters using those fonts. If that sounds quaint now, at the time it caused outrage in the traditional world of typeface creation and distribution. As well as correctly proposing a future for the type industry (that link with production again), the fonts and their packaging can be seen as a template for all Brody’s subsequent work, and in particular the new book, itself a provocative piece of editorial design. (See ‘Postmodern jam session’ in Eye 83.)

Looking back at the earlier two volumes, they are tame and traditional by comparison, every piece of work being given time and space to breath. The graphic language of the title is restricted to the content of the work shown in images, and argued for in the texts. For volume three, Brody repurposes his work archive to establish a genuine graphic language from page to page – this is a book of images, yes, but also the book itself has been conceived as one vast image.

If this makes it difficult to parse, so be it. Brody has always been ready with a provocative soundbite and, during a recent live interview at the magCulture Shop, his definition of graphic design as ‘friction’ hit the mark for me. Graphic design may once have been defined as helping the reader easily access information (hints of our dull obsession with UX design there), but rules are there to be broken – why shouldn’t an expressive form of visual design be difficult instead of easy?

This new book, then, oozes friction. It has been produced to be enjoyed as a visual experience beyond a mere taxonomy of work. Huge projects appear as thumbnails, small projects get spreads. The reader can unpick these pieces and read the texts (by Brody, Adrian Shaughnessy and others), which jump between description, polemic and lecture transcriptions. It works on multiple levels, a unique publication that deserves its place on our studio shelves alongside those earlier volumes.

Spread showing Brody’s type design Popaganda, with text bleeding off, set on the page at opposing angles and thumbnail insets of its use in Arena Homme+, for which it was designed.

Jeremy Leslie, editorial designer, writer, curator, magCulture, London

First published in Eye no. 105 vol. 27, 2023

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.