Summer 2006

Instant Tarkovsky

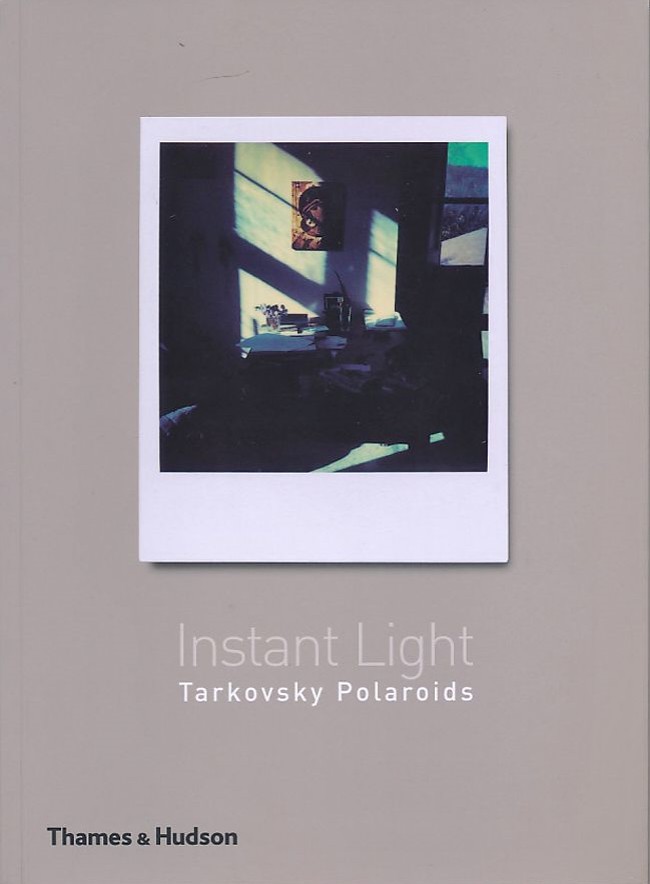

Instant light: Tarkovsky Polaroids

Edited by Giovanni Chiaramonte and Andrey A. Tarkovsky<br>Thames & Hudson, £16.95

Film directors who began their careers as stills photographers are not as common as might be expected. Stanley Kubrick is perhaps the most celebrated example. Larry Clark is another. Considering the epic stillness found in the films of Andrey Tarkovsky (1932-86), and considering his grand obsession with the filmic suspension of time, it is not surprising to discover that the visionary Russian (actually born in Belarus) director was also a gifted snapper.

Tarkovsky is one of the great aesthetic filmmakers. His films are cinematic poetry, suffused with a lambent intensity rarely found in contemporary cinema. He is the antithesis of modern Hollywood filmmakers. Tarkovsky is about introspection and, above all else, slowness, while modern cinema, with its motorised editing and attention-grabbing micro-narratives, is about extroversion and frenetic speed. As Maximilian Le Cain has written: ‘… he (Tarkovsky) proposed a cinema based on the rapt observation of the present moment as opposed to a plot-driven preoccupation with what will happen next.’

The famed Tarkovskian preoccupations with memory, decay, melancholy, nostalgia and the effects of light, can be seen in the 60 Polaroids assembled in this handsome little book. Once you get past the initial shock of finding his distinctive imagery crammed into the square, white-bordered format of the Polaroid – and not the more generous ratios of the cinema screen – you realise that Tarkovsky’s oeuvre is well suited to the static medium of the still photograph.

The Polaroids are reproduced at actual size and form a dreamlike mapping of Tarkovsky’s elegiac sensibility. The images were taken between 1979 and 1984, and document time spent in Russia and in Italy, where, exiled from his native land, the director spent his last years. They show tender scenes of family life, mist-festooned landscapes and Vermeer-like domestic interiors.

In the age of digital photography, Polaroids are a neglected medium. They have their own aesthetic flavour: a sort of nostalgic, almost vulnerable quality that makes them closer to paintings than to photographs. Since paintings cannot be ‘recreated’ by going back to a negative, they share with Polaroids the distinction of being ‘originals’ – a state that makes them vulnerable to both damage and the passing of time, which in turn imparts a quality of preciousness.

For Tarkovsky, as a master of slowness and stillness (he wrote a book of film theory called Sculpting Time), the difference between his photography and his filmmaking is slight. Screen ratios apart, it is almost as if the images in this book are frames from his movies. Yet these poignant glimpses of Tarkovsky’s life away from film-making throw up the difference between shooting photographs and shooting film: in film, every image is part of a sequence of images; the director and cinematographer have to concern themselves with the next image and the one after that, as well as the frames that have gone before. With stills photography, there is only the single moment.