Summer 1993

Stamps and the public interest

Neville Brody

Pierre Bernard

Erik Spiekermann

Jan van Toorn

R. D. E. ‘Ootje’ Oxenaar

Design education

Reviews

Visual culture

The Boundaries of the Postage Stamp

Jan van Eyck Academy, Maastricht, 12 March 1993Since Rowland Hill’s introduction of the Penny Black in 1840, the postage stamp has been the easiest, cheapest, and most colourful way of proving pre-payment of postage. But the advent of the telephone, modem, fax, mechanical franking and international courier services has left the postage stamp with a much reduced role. In the Netherlands, letters and parcels bearing a stamp account for only 10 per cent of all mail handled by the PTT. Yet each year the PTT publishes some 12 sets of special stamps commemorating various anniversaries and centenaries, in addition to the standard definitive issues.

That a million Dutch people are prey to an affliction called philately goes some way to explaining this seemingly anachronistic over-production of gummed perforated emphemera. The director of the PTT’s philately business unit, René Kaarsemaker, who is responsible for selecting the themes for commemorative issues, clearly knows which side his bread is buttered on when he says: ‘It is sound business practice to take account of the desires and interests of the philatelists.’ And the PTT appears equally aware of the potential for sales to those similarly afflicted abroad.

So if postage stamps are to remain, if only to satisfy those who would rather stick them in albums than on envelopes, is it not incumbent upon the PTT to preserve its unrivalled tradition of design excellence? Or would it make ‘sound business’ sense to give up its pretence of socially responsible paternalism in order to follow the market? Are the two incompatible? Kaarsemaker, at least, is clear: ‘Dutch stamps have a reputation for unusual [by which I presume he means good] design, although the philatelists are not always charmed by this unconventionality.’

As recently privatised concern with a virtual monopoly over telecommunications, the PTT is faced with many questions. In order that these be more widely debated, and to add a few of their own, the director and staff of the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht recently organised a day-long symposium in conjunction with the PTT entitled ‘The Boundaries of the Postage Stamp.’ The academy was also the venue for an exhibition celebrating 1992’s stamp issues, 11 sets of which were designed by graphic designers or illustrators from other member states of the EC, including such luminaries as Neville Brody, Peret Torrent, Italo Lupi, Pierre Bernard and Erik Speikermann. The last two were invited to speak at the symposium along with Professor Oxenaar, head of the PTT art and design department, and Hugues Boekraad, a writer on design theory and history and a member of the academy faculty.

Veteran stamp designer Jan van Toorn, acting as host for the day in his capacity as academic director set out his expectations for the tone of the discussions in his opening address. He made it clear that the symposium was not an excuse to applaud the PTT’s past achievements, but an opportunity for a searching debate on the impact and responsibilities of graphic design in the public sector. In an uncompromisingly theoretical 30 minutes, he challenged designers to face up to their obligations as co-authors of visual ideology for public consumption – to acknowledge and reflect critically upon their position in order to win back their role as intellectual mediators. In Van Toorn’s opinion, graphic design has been for the most part colonised by the interests of marketing, advertising, and public relations and most designers ‘find themselves incapable of reformulating an attitude related to the public interest.’

That few of those present had much idea of what Van Toorn was talking about became apparent during the open discussion at the end of the afternoon. First, however, we were asked by the head of the academy’s design faculty, Gerard Hadders, to bear in mind a number of questions arising from Van Toorn’s speech. What is the role of designers and their work in society? What is communication in this visually packed world? Why is there a distinction between advertising and other visual output in some places and not in others? What is the difference between the state and private sector?

As if to confirm that none of these questions was of interest to anyone, there followed a vaudevillian succession of one-man shows. First up was Kaarsemakers, who literally explained what a postage stamp is, while being upstaged by a slide projector with a mind of its own. We were then treated to Professor Oxenaar’s rendition of ‘These are a few of my favourite things,’ a thoroughly impressive exposition of the high points of the PTT’s long and admirable advocacy of quality design. It is a shame that since he was performing under the watchful eyes of the powers that be within the PTT, Oxenaar made no mention of the possible threat to that tradition.

After lunch Pierre Bernard and Erik Speikermann lamented the state of design in the public sector in Paris and Berlin respectively and talked warmly of their experience of designing stamps for the PTT. While their descriptions of the design process were fascinating, they did little to sharpen the debate. Finally Hugues Boekraad gave an art-historical survey of the Dutch postage stamp that was too unwieldy and scholarly to keep the attention of most of the audience.

In the discussion that followed, chaired by Hadders, it became obvious that everyone was speaking a different language – though the official one was English. Hadders and Van Toorn proved unable to focus the participants’ attention on the relevant questions, and the witty asides and anecdotes from some of the panellists that earlier in the day had seemed like consummate showmanship became merely trivialising. Much time was wasted trying to find a shared terminology, and the end of the day the symposium suffered from trying to answer too many questions of too wide-ranging a nature with little common intellectual framework.

Among all the confusion, the clearest position, and the simplest, was that of Kaarsemaker, who seemed oblivious to the more cerebral intentions of the day’s discussion. Stamps are, after all, nothing more or less than his business. As he noted in his introduction, ‘Research is currently being conducted to find out what the public wants and requires in this filed. The result may well influence future design.’

Gerard Forde, design writer and exhibition organiser, Rotterdam

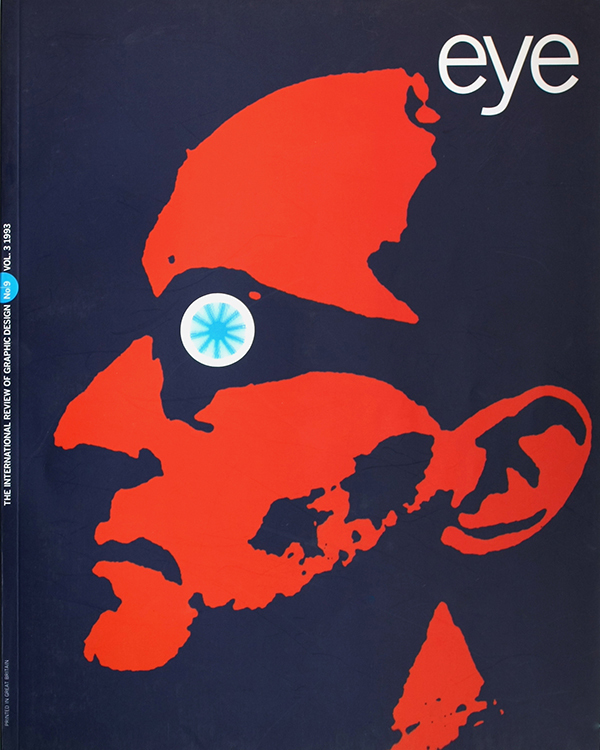

First published in Eye no. 9 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.