Autumn 2019

Thinking machine

AI: More than Human

Barbican Centre, London. Curated by Suzanne Livingston and Maholo Uchida. Exhibition design by Tonkin Liu. 16 May – 26 August 2019

In the vestibule of Level G at the Barbican a man stands before a large black screen. As he shifts awkwardly from side to side a rudimentary digital stick man pops up in front of him, echoing his movement. The man performs ever more complex choreography, lunging, kicking and flailing his arms while his reflected ‘self’ mirrors every move, becoming increasingly complex as it maps and records movement in real time, eventually filling the screen with twitching blobs and lines. It has evolved. The man moves away and the creature disappears, but the data, the real prize from this encounter, remains. Universal Everything’s Future You signposts visitors to a darkened labyrinthine Curve Gallery where the majority of the works in ‘AI: More than Human’ are situated. The space is made more disorientating by suspended columns of diaphanous fabric, digital screens, glass cases for ‘artefacts’ and audio – lots of it.

Top: Myriad (Tulips) by Anna Ridler, an installation of Polaroid photographs of tulips, part of ‘AI: More than Human’, at London’s Barbican Centre. Photograph: Tristan Fewings / Getty Images.

Anna Ridler’s film Mosaic Virus dreams tulips into life by means of the algorithm used to track and image fluctuations in Bitcoin value. Drawing on a data set of 10,000 Polaroid photographs, the work shows myriad tulips which bloom and close according to the Bitcoin price. The work references the mania for speculative investment that gripped Dutch colonial traders in the seventeenth century, making a correlation with the promise of crypto-currency bonanzas in today’s febrile financial climate. Tulip breaking virus (or mosaic virus) is the degenerative disease that caused stripes and mutations in the tulip, increasing their desirability, value and mortality. Ridler’s work, also displayed as Myriad (Tulips), creates an intriguing intersection between human, machine, machine learning and AI; all 10,000 photographs have been meticulously categorised – a nod to the grinding realities of data collection.

In section one of the show, The Dream of AI, we consider the social and historical context of animism through the dual lenses of the Golem myth and Japanese Shintoism. Stefan Hurtig and Detlef Weitz’s cinematic collage of artificial life forms from film and TV is cleverly unified and helps set the tone. Kode9 (aka Steve Goodman) presents an audio exploration of the Golem, which, he says, opens up ‘a whole series of theological questions in relation to technology’.

Section two, Mind Machines, offers a timeline of significant historical events, people, artefacts from Ada Lovelace to Garry Kasparov, neural networks and machine learning. Mario Klingemann’s generative piece Circuit Training asks participants to contribute to the learning of a machine by identifying what they find interesting in an image. Despite the uninspiring visual results (and the problematic nature of the aspiration) the piece hints at a more profound change in image production. It is possible to imagine bespoke illustrated advertising evolving in real time to meet the needs of increasingly fickle and desperate-to-be-individual consumers. Alexander Mordvintsev’s DeepDream: The Artificial Pareidolia is a bittersweet psychedelic mutation where visual homogeneity reigns supreme. Perhaps more commentary than offer of creative possibility, The Artificial Pareidolia emphatically barks the mantra of algorithmic AI ‘If you like that then you’ll love this’.

Joy Buolamwini’s work, AI, Ain’t I A Woman, stands out as an unambiguous critique of the very human failings of AI and reveals the implicit bias in machine learning. Her spoken word piece, which identifies how AI fails to recognise iconic Black women as women, is arguably the most important piece in the show. Laurence Lek’s 2065 portends a future beyond work, defined by games-based gratification. Ana Cuna and Luis Sanchez’s animated film AI in China is an upbeat but ultimately chilling exploration of how ‘City Brain’ programs are monitoring and surveying behaviour in order to control the urban environment.

‘AI: More than Human’ cuts across the material possibilities of AI in the realms of biomedicine, performance, deepfake media, sustainability, distraction in the form of info /entertainment and terraforming (just in case it all goes horribly wrong!). The central question, that of humanity’s relationship with AI, struggles to resolve itself in this overloaded context. While assertions are made for AI’s burgeoning creativity, the question of consciousness, who owns it and where it comes from, is buried in the dense layers of information and noise (this is a noisy exhibition).

So, what about graphic design, illustration and visual communication in this brave new world of automated creativity? Safe for the time being but there are warning signs. Undoubtedly the sophistication and scope of neural networks and machine learning will provide cost-effective ‘solutions’ to communication problems but the sheer weirdness and unpredictability of the human brain may well prove to be its short-term salvation.

The curators of ‘AI: More than Human’ suggest that AI is ‘everywhere and nowhere’, a phantom-like presence, ominous, benign, liberating and oppressive, all and none of these things. In the end the mania surrounding diseased tulips tanked the Dutch economy; vastly inflated prices coupled with the inherent instability of the product caused an economic crash. With this in mind Anna Ridler’s film may inadvertently guide how we consider AI and its promise of limitless creative possibility.

Darryl Clifton, Illustration programme director at Camberwell College of Arts, London

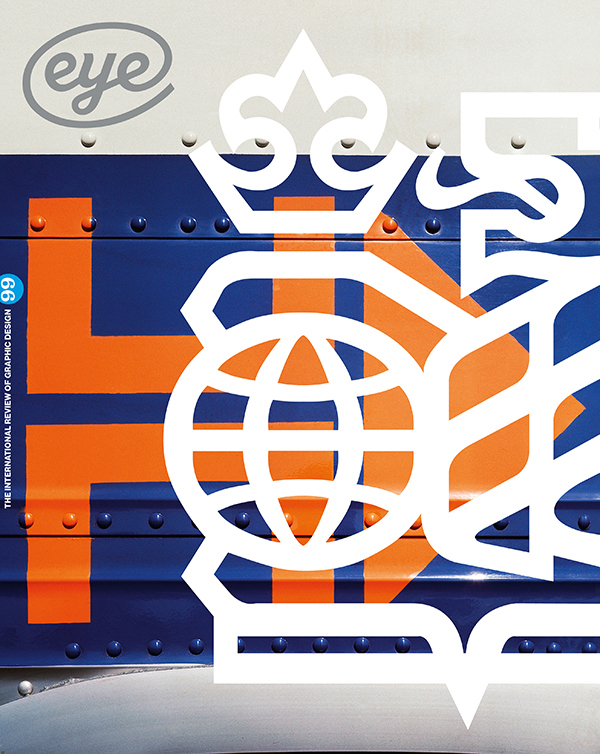

First published in Eye no. 99 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.