Friday, 11:00am

3 February 2017

Out of this world

Flatland Ep1

By Edwin A. Abbott<br> Epilogue Press, Chris Lauritzen, $65<br>Epilogue Press’s Flatland re-interprets the 1884 classic for the age of popular science. Review by Kevin J. Hunt

Flatland is a cult novella by Edwin A. Abbott, first published in 1884, a classic situated somewhere between fringe populism and elite literature. It playfully (and earnestly) combines mathematics and morality in an inspired piece of conceptual storytelling, writes Kevin J. Hunt.

The deceptively simple tale of a square ‘flat’ character living in a two-dimensional world who has to countenance the possibility of a third-dimension of spheres and cubes – as well as other shapes, spaces and forms with depth – neatly clarifies the philosophical quandary of perceiving a world greater than the one currently known.

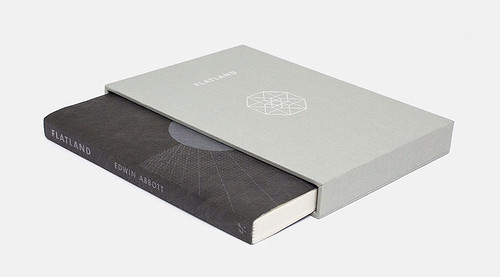

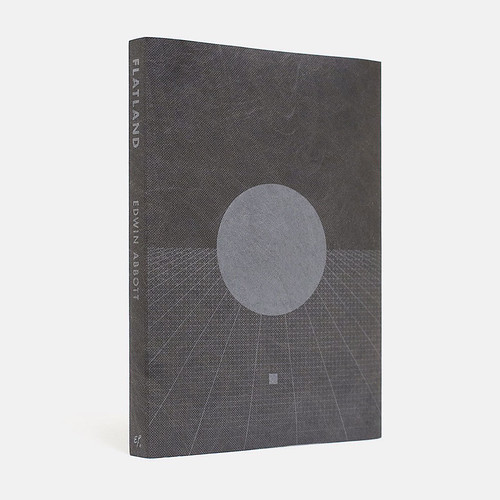

Epilogue Press’s slip-cased edition of Edwin A. Abbott’s classic novella Flatland. Photo: James Han.

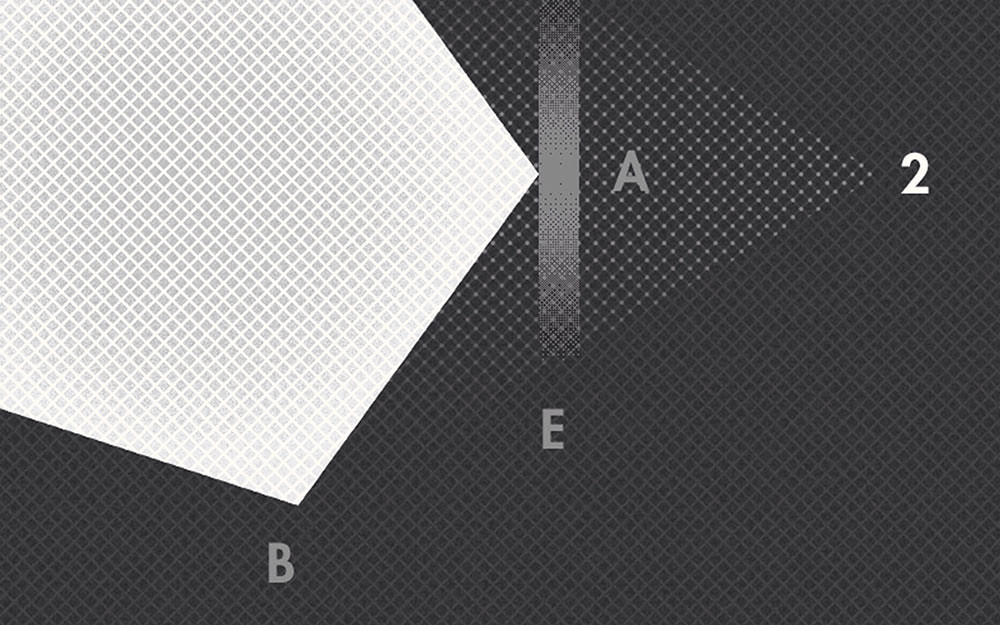

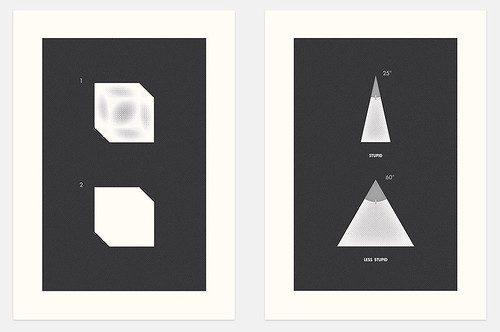

Top: Detail from ‘On the other hand in the case of (2) the Physician…’

Chris Lauritzen’s Epilogue Press has republished Flatland in an edition that elegantly conveys the multi-sensory world described on the page through an enhanced set of complementary drawings and detailed graphic design that ‘feels’ just right. To say this edition ‘feels’ right is not just to comment on the pleasurable touch of the smooth pages and slightly textured cover, the weight and size of this small but powerful book, and the satisfyingly precise and solid slipcase that contains this edition of Abbott’s world. It is to comment on the idea that Flatland is inherently concerned with sensory perception and the physical ‘rules’ of space, and to recognise that Epilogue Press communicates these core ideas through graphic design.

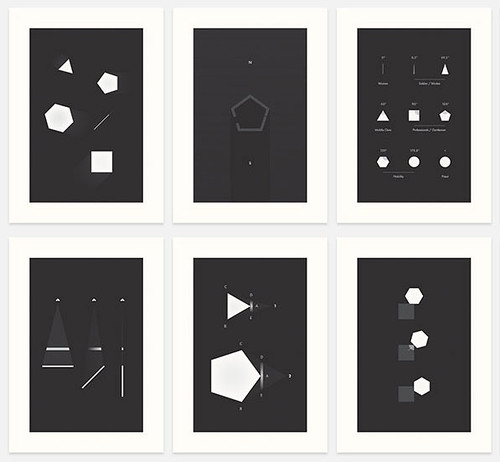

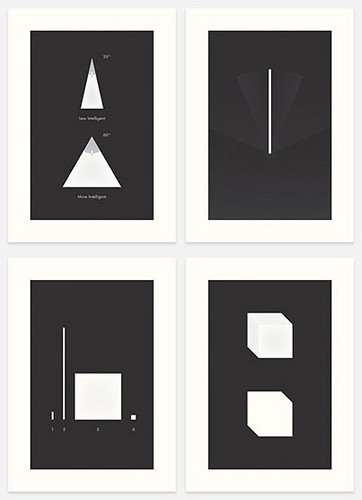

Selection of designs from the Epilogue Press edition visual appendix of new diagrams.

In neurology, the term cross-modal correspondences refers to the way in which an experience in (at least) one sense modality can generate a corresponding response in another sense modality. For example, hearing certain types of music can make us feel high or low; some food or drink can taste sharp or mellow; and some images, including graphic design, can feel energetic or fast-paced whilst other visual experiences feel calm or serene. Such cross-modal correspondences are broadly shared as experiences by a majority of people, assuming the social / cultural context is generally consistent, and crosstalk between the senses is part of how we empathize and communicate with others in a sensory-informed way.

Oliver Sacks discusses the role of mental imagery in The Mind’s Eye, suggesting that both visual and verbal imagery are integral to how most of us think. This can include starting a thought process in one mode in order to transform it into another. In particular, Sacks references Einstein’s reflective observation that he would visualise signs or images as psychical entities in the initial part of his thought process before then converting his (ground-breaking) ideas into conventional words, or other appropriate signs, which he sought for ‘laboriously’ at a secondary stage of interpretation.

Part of what the Epilogue Press edition of Flatland visually communicates is how scientific and mathematical thinking is a highly creative and sensory experience, especially where epistemological questions are being explored. The world Flatland brings to mind shares qualities with Einstein’s visualisation process, and broadly recalls the illustrated version of Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time (1988) as well as the mathematical imagery used in Errol Morris’ engaging 1991 documentary of the same name. Even more familiar is the use of visual explication within numerous sci-fi films, where the theoretical model of a wormhole or the interpretive possibility of time travel is communicated by bending a sheet of paper (representing space and time) and poking a pencil through the two points that subsequently meet.

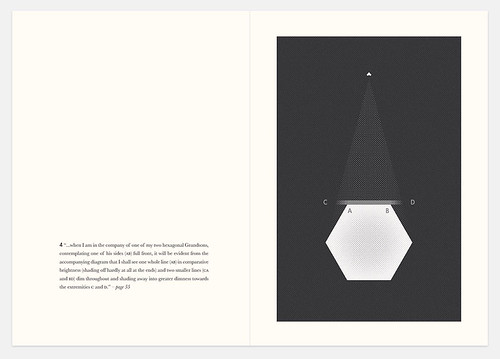

Images are ‘titled’ as the quotation they accompany from within the text … ‘… when I am in the company of one of my two hexagonal Grandsons…’

‘… to my eye the appearance is as of an Irregular Figure whose inside is laid open to view’ and ‘… in that same proportion their acute angle (which makes them physically terrible) shall increase also and approximate to their comparatively harmless angle of the Equilateral Triangle’.

We live in an age where dark matter and black holes; life on other planets; simulated lifeforms and artificial intelligence; variations of string theory, and the theoretical possibility of multiple dimensions, are regularly discussed in popular science programmes and specialist segments of mainstream media. As science, technology and culture increasingly embrace expanded possibilities of space and time, challenging our expectations of the future and what might be achievable, this edition of Flatland feels like it is closely related to this larger picture of emerging and evolving 21st century thought.

In terms of cross-modal correspondences, the reader ‘hears’ the words being read off of the page (albeit silently read or ‘heard’ as an internal process) which can prompt visualisations of Flatland within the mind’s eye as well as potentially triggering a tactile response – neurologically ‘feeling’ the edges of the characters and sides of the world being described. This multi-sensory experience is encouraged, in part, by the inclusion of illustrations by the original author. However, these pictures tend to capture the essence of Abbott as a Cambridge-educated schoolmaster trained in classics, theology and mathematics. They evoke his presence as a nineteenth century scholar using small, descriptive, hand-drawn diagrams to expand his prose, reminding us of the creative intelligence of the author as he conveys the charm of the Flatland tale.

Selection of designs including (bottom left) ‘A Female at birth would be about an inch long [1], while a tall adult Woman might extend to a foot [2]’.

By contrast, the Epilogue Press drawings, appropriately designed using precise computer modelling, evoke the essence of Flatland’s metaphorical engagement with the space-time continuum. The black cover, overlaid with a diagonal grid of fine silver grey lines, projects an expansive sense of space that is exactly halved by the horizon. A regularised grid fills the lower half of the image to create an abstract but distinct geometrical landscape. Reminiscent of graph paper (and also printed in the same silver grey) this grid is given depth by a series of lines that converge on an unseen vanishing point positioned behind a sphere that dominates the centre of the image. Shaded as though lit from behind, the sphere looms above a small, purely shaped, square – capturing the decisive moment when the two-dimensional Flatlander encounters the three-dimensions of Spaceland and beholds the knowledge of ‘a new world’.

Each of the 24 new illustrations follows a similar aesthetic of delicate but distinct silver grey (and occasionally white) on black to convey precise and clear information. These designs are consistent in their minimalistic elegance and specific, mathematical, evocation of the rules and laws that define Flatland and its theoretical boundaries. There is a Modernist beauty to the whole edition that simultaneously evokes the unknown postmodern wonders imagined by theoretical physics. Even the cool silver grey lines with their understated but decisive characteristics hint at the pencil marks of the schoolmaster while pointing towards the calm, unflinching, logic of a simulated (perhaps artificially intelligent) world.

In this new edition, Epilogue’s Flatland projects a strong sense of the value of this book as an epistemological experiment that is potentially more relevant than ever. Epilogue takes the theoretical and sensory world described on the page and, through an instinctive awareness of cross-modal correspondences, gives that world a satisfying and elegant visual form that feels as good as it looks.

Book cover design showing ‘… I looked, and, behold, a new world!’ Photo: James Han.

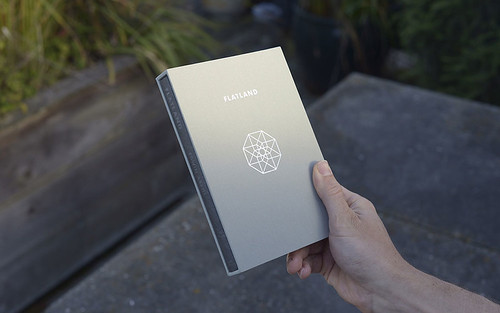

Flatland is the first project to be released by Epilogue, a small design and publishing studio in San Francisco, California. It was funded, in part, through a Kickstarter campaign. Photo: James Han.

Kevin J. Hunt, senior lecturer in the School of Art and Design, Nottingham Trent University

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can also browse visual samples of recent issues at Eye before You Buy.