Winter 2017

Systematic play

Using intuition, research and process, the work of Armin Lindauer and Betina Müller revitalises connections between art, design and science

Graphic designers and educators Armin Lindauer and Betina Müller have a vision for 21st-century design. Passionate about the connections between art and science, they propose a ‘Copernican Revolution’ in the ways we think about creativity, advocating a central role for systematic play that combines rationality with invention.

At the heart of their approach is admiration for the creativity that drives science forward, as well as a recognition that some kind of structure exists within even the most open-ended artistic practice. In other words, scientists are much more creative than they are often given credit for and artists intuitively use some kind of structure within their creative practice. There is more common ground between art and science, in terms of process, than is often acknowledged. Lindauer and Müller share an acute awareness of the expansive meeting point between structured and intuitive thought where scientific and artistic processes become integrated. They see huge potential for experimental design as a means of bridging the perceived gap between art and science, revitalising the fundamental connections between these too often falsely separated worlds.

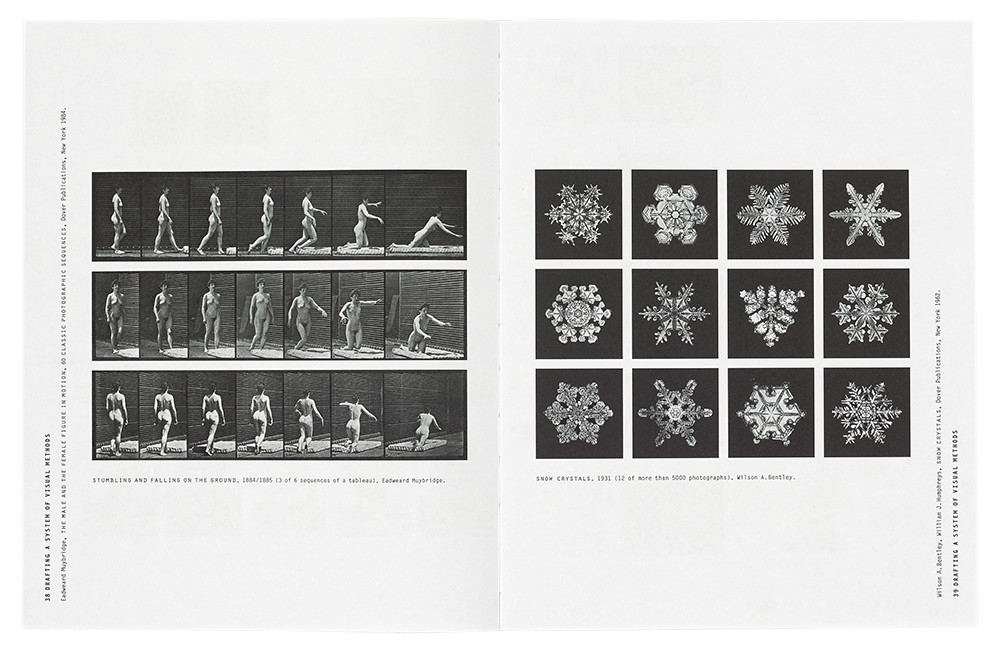

Image above: Photography as a gradual process

On the borderline between art and science, Eadweard Muybridge systematically investigated human and animal sequential movements. Wilson A. Bentley’s photographic portraits of snow crystals catalogue more than 5000 unique structures and forms.

The legacy of Helmut Lortz

What Lindauer and Müller propose is nothing new. As they write in the introduction to their meticulously crafted book, Experimental Design: Visual Methods and Systematic Play (2015), there are ‘more similarities and connections between scientific and artistic work than generally supposed.’ And yet, if their approach were to inspire a re-evaluation of design thinking and arts education the results could be revolutionary, sparking a paradigm shift based around the deceptively simple question: ‘How do you use a system to tap into creativity?’ To understand the implications of Lindauer and Müller’s research it is purposeful to consider where their fascination with scientific process comes from and how this became embedded within their creative practices.

Lindauer and Müller first met as design students in the Hochschule der Künste Berlin (HDK, later Universität der Künste Berlin, UdK) where they were both taught by Professor Helmut Lortz. Lortz (1920-2007) taught for 29 years as head of the class for Experimental Graphics. As well as being an inspirational teacher, he was a graphic designer and illustrator who produced book covers, illustrations, posters, signs and stamps. He also published books of his distinctive hand-drawn studies. His work systematically and unpredictably explores relationships, structures and the power of visual communication, often showcasing the evolution of an idea from a simple concept or starting point through a complex range of multi-faceted possibilities. Seeing Lortz’s work brings to mind the brilliantly inquisitive line drawings of Saul Steinberg combined with a more analytical methodology. And his personality, work and teaching – promoting experimental play structured by intuition and adaptation – made a significant impression upon his students.

As Lindauer and Müller independently developed their design practices and educational careers, both became aware of Lortz’s profound impact upon their creative processes and pedagogical approaches. In 2004 they began reviewing the archive of Lortz’s work and that of his students, held at UdK. The array of visual processes, catalogued over three decades, developed from the basic principle Lortz was constantly probing: the relationship between innovative design and the boundaries within which experimental development takes place. Any design project, by definition, has boundaries. Such boundaries can be incredibly tight. And, in many cases, tighter restrictions lead to more far-reaching design responses. Examples might include limiting experimentation to a single image or icon; precise restrictions upon the form being explored; working with set geometric forms; or a combination of restricted values across form and content that define the parameters of any given design brief.

Interpretation and intent: The perception of the designer always shapes the message communicated by their work. Each interpretation of the Alfred A. Knopf logo (including drawings by Triboro, see Of Two Minds in Eye 95 and Jonathan Hoefler) investigates expression by means of representational style.

Methodology of play

That limitations can fuel creativity is self-evident as a design principle. But by building upon Lortz’s archive (as well as personal design-led experiences) Lindauer and Müller have pushed further, seeking a deeper understanding of the way open-ended play and structured boundaries are related. Design thinking in a day-to-day sense can be comparatively banal. As Lindauer observes, ‘purely client-orientated design unfortunately does not lead to really major discoveries.’ The parameters of commercial projects, while often producing beautiful work, are usually determined to fulfil pre-existing goals within the marketplace, such as communicating a brand identity or delivering a specific message. Lindauer and Müller’s research focuses instead upon the relationship between creativity and structure at a more fundamental level: challenging unstated rules and approaches to problem solving; deconstructing acculturated practices of creative and analytical thinking; and undermining the presumptions of the Western philosophical tradition – particularly since the Enlightenment – that have generated a false dichotomy between art and science.

‘During the Enlightenment “reason” was accorded primacy,’ says Lindauer. ‘Science was awarded the ideal of objectivity as a result of measurability and art became imbued with everything that was subjective, sensual and emotional.’

Lindauer also notes, with reference to philosopher Paul Feyerabend, that from antiquity to the Enlightenment there was no separation between art and science; every discipline was an ‘art’, such as the art of navigation, the art of healing and the art of rhetoric. Though the processes of learning and practising were similar, the results and applications were significantly different. But in the age of Enlightenment science and art were split apart. Objective reason came to dominate and scientific rationality pushed the experimental qualities of art into the background. Despite increasing discussion of a rapprochement between art and science since the 1980s, breakthroughs and discoveries are now assumed to be driven by science and technology: the result of objective reasoning and empirical research.

But some of the most innovative and progressive advances that influence the way we live are the result of scientific rigour combined with intuitive, lateral and creative leaps of the imagination – the cultural arena primarily associated with art and design.

Richard Feynman, one of the great physicists of the twentieth century, often described how his research interests started with ‘play’. Feynman was instinctively drawn towards playing with ideas, underpinned by his knowledge of theoretical physics, and it was this celebrated and self-acknowledged ‘playfulness’ that led to his Nobel Prize-winning Feynman diagrams. Feynman’s work influenced the development of lasers, transistors, computers, nanotechnology and all manner of telecommunications, profoundly altering our understanding of the subatomic universe.

Objectivity alone did not deliver these breakthroughs and Feynman’s initial investigations often began with personal curiosity; there was no predetermined goal or intended result in mind. Instead, he intuitively applied an experimental methodology that allowed for the evolution of an idea by responding to the outcomes of systematic play. In this manner, Feynman selectively structured the direction of his research as an open-ended process that refined itself towards a conclusion. This is the kind of thinking – blending creativity with structured progress – that Lindauer and Müller see as a model for 21st-century design: experimentation through play in order to test, explore, evolve and develop new ideas, solutions and methodologies.

Yet in contemporary art and design, the term ‘experimental’ is used as a metaphor for something intended to be seen as avant-garde or ‘alternative’. Lindauer and Müller feel this terminology, with its implication of something ‘allegedly inexplicable’, is often used to gloss over the shortcomings of work that is merely arbitrary or nonsensical. By contrast, their vision for art and design embraces the ‘experimental concept’ in its more specific sense – the sense currently aligned with science – as an evolving search for knowledge explicitly related to making and doing. In effect, Lindauer and Müller propose a reintegration of artistic and scientific processes at the core of the design process: a unifying of technique and knowledge capable of merging specialisations from across the arts and sciences.

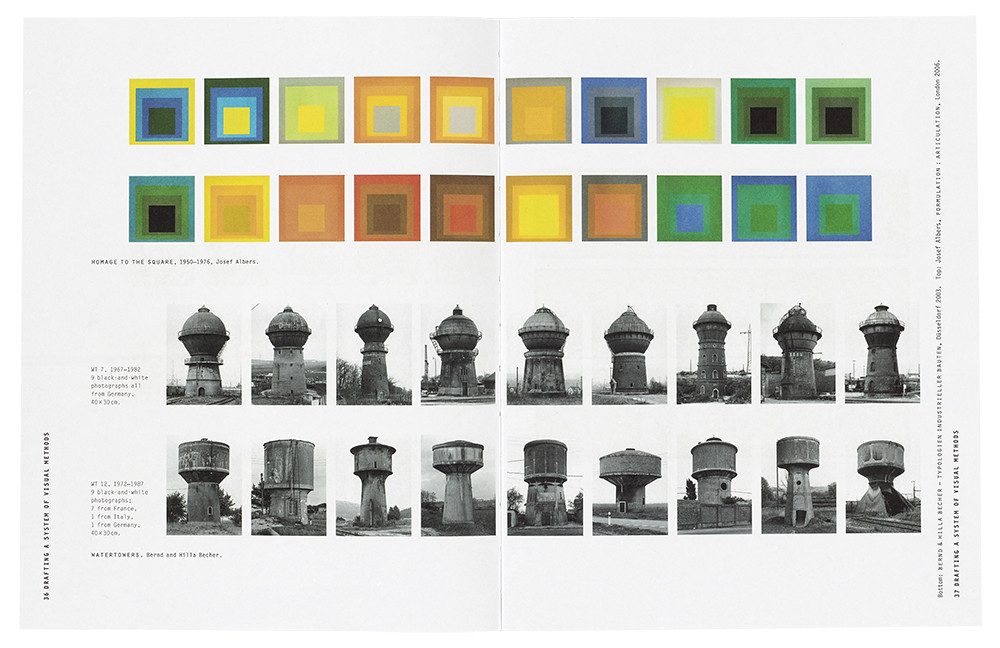

Cultural evolution: Driven by human invention and targeted change, artists and designers select which adaptations and variations enable their work to evolve. Josef Albers’ Homage to the Square series includes more than 1000 explorations of colour perception and colour relationships. Bernd and Hilla Becher’s typologically organised Water Towers show the diversity of their subjects within tightly controlled representational boundaries.

Think laterally

Feynman-like breakthroughs that win Nobel Prizes are rare. But part of the physicist’s success was not just his genius with mathematics, it was his capacity to think laterally. A core element of Lindauer and Müller’s approach requires asking a series of basic questions about a design brief, problem, or area of intrigue. The aim is to understand and explore the constituent elements, but without initially having any specific developmental direction in mind. The process then has to evolve meaningfully as the creative possibilities reveal themselves, leading towards more complex and ingenious responses.

Müller describes the range of possibilities that emerge from the simplest of exercises, such as representing an everyday object like a cup. This can begin by identifying the cup as a form with a body and a handle; then considering a further set of characteristics such as proportions, density, surface, pattern and material; working visually, the options can be explored from different perspectives, using different styles, and the designer can begin to play around with the possibilities. From the array of cups, handles, angles and ideas new questions emerge, such as which representational medium to use: photography, film, drawing, painting, computer modelling and so on. Surveying this wealth of ideas leads to selecting the most interesting, placing the variants next to one another, and making comparisons and choices in order to recognise which ‘solution, idea or image is better, worse or most unconventional.’ By testing, comparing, rejecting and reworking in an open-minded way a remarkable number of variables begins to materialise; each variable can then be explored by imposing tight parameters to test the boundaries of what is possible. Previously unconsidered combinations and unpredictable outcomes develop, pushing the designer to ‘break free from conventions and not get trapped in a comfortable favourite style with which you are merely quoting yourself.’ New prospects might then emerge as the concept of a cup becomes the focus of experimentation. The aim is innovation, even within a basic task, but with the potential for expansive development depending upon how the experiment is set.

This process mirrors the principles of evolutionary biology, whereby variations and adaptations occur in response to environmental factors and the suitability of those developments determine which lifeforms, behaviours, mutations and combinations survive and advance. Biological evolution is literally a creative process guided by chance. One of the key differences between biological and cultural evolution, explored by Lindauer and Müller, follows the work of evolution historian Thomas Junker, who argues that cultural evolution is driven by human invention and targeted change. Human creativity has the same diverse benefits as biology in terms of chance and serendipity, but this is combined with the power to control the evolutionary process by selecting which advances to pursue, based upon which inventions appear to be the most advantageous and progressive. As Junker observes, this is why ‘cultural evolution runs at a speed that is a thousand times higher than biological evolution.’

From Albers to the Bechers

The type of process Lindauer and Müller advocate for design is therefore already at work, driving cultural evolution forward. But it is generally only recognised with hindsight, illuminated by switching attention from creative results to the experimental processes that produced them. This shift in focus is presented in the opening section of Lindauer and Müller’s book, Experimental Design, as a lucid but selective overview of the relationship between art and science in western culture. Viewing the similarities between art and science from this shared perspective produces a striking array of high-profile examples where structure and play are intuitively integrated.

Visual artists embrace scientific processes by applying a form of structured methodology to their work, most notably when they create experimental studies in a series. Claude Monet’s 38 tableaux of La cathédrale de Rouen (1892-94) are essentially investigations into the changing effects of light. Gustave Courbet’s numerous versions of La vague (1865-69) revisit and refine the symbolic image of a breaking wave at least 60 times, exploring both formal and conceptual possibilities within a single motif. Picasso painted (or, technically, overpainted) 29 versions of The Painter in gouache and Indian ink within a two-week period in 1964, each beginning from the same reproduction of his own self-portrait in oils – an intense revisiting of identity and visual style. Josef Albers’ 25-year series Homage to the Square (1950-76) produced more than a thousand studies of colour perception and colour relations in a range of media (paintings, drawings, prints and murals). And Bernd and Hilla Becher’s multiple series of black-and-white documentary photographs, such as Water Towers (1972-1987), regularise the impact of composition and light in order to focus upon the history and character of industrial architecture.

Equally, the world of science is full of influential thinkers who embrace artistic processes by adopting creative visualisation, open-ended play and non-linear or lateral reasoning. The mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, renowned for his work on fractal geometry, stated that ‘my whole life long I have dealt not with formulae but pictures in my mind.’ Einstein would visualise signs or images in his mind’s eye before converting conceptual ideas into conventional scientific language at (what he considered) a laborious secondary stage of interpretation. And Arthur Koestler described similar (visually led) processes in scientists such as Max Planck, the father of quantum theory, who wrote about the need for ‘a vivid intuitive imagination’, and Michael Faraday, who would visualise the lines of force within the universe as curves in space ‘as real as if they consisted of solid matter.’ In his book The Act of Creation, Koestler cites a study of leading mathematicians and physicists whose processes are revealed to be visionary in both the metaphorical and literal sense, with a majority defined as ‘visual thinkers’ who would work primarily with images (on paper or in the mind’s eye) to develop ideas.

Drawing upon these and other examples, selectively chosen from an extensive range of reference points, Lindauer and Müller build a compelling case for the power of visual thinking as an essential part of the experiment-led design methodology their work espouses. One of the neatest ways of condensing this dialogue between art and science is through Edward de Bono’s familiar terms ‘vertical thinking’ and ‘horizontal thinking’, which Lindauer and Müller revisit to help conceptualise their fusion of logical and selective progression (a vertical depth of purpose) with lateral and discursive thinking (a horizontal and playful breadth of possibilities). But the heart of the process lies in giving oneself the creative freedom to ‘[do your] thinking with a pencil in your hand.’ Designers must be willing to plunge into the absurd and the unrealisable in order to return surprising results and new directions, and then have the patience to explore the variables until something unpredictable but usable evolves. As Müller says, ‘you don’t judge anything initially, but permit every single idea, after which you make a selection.’

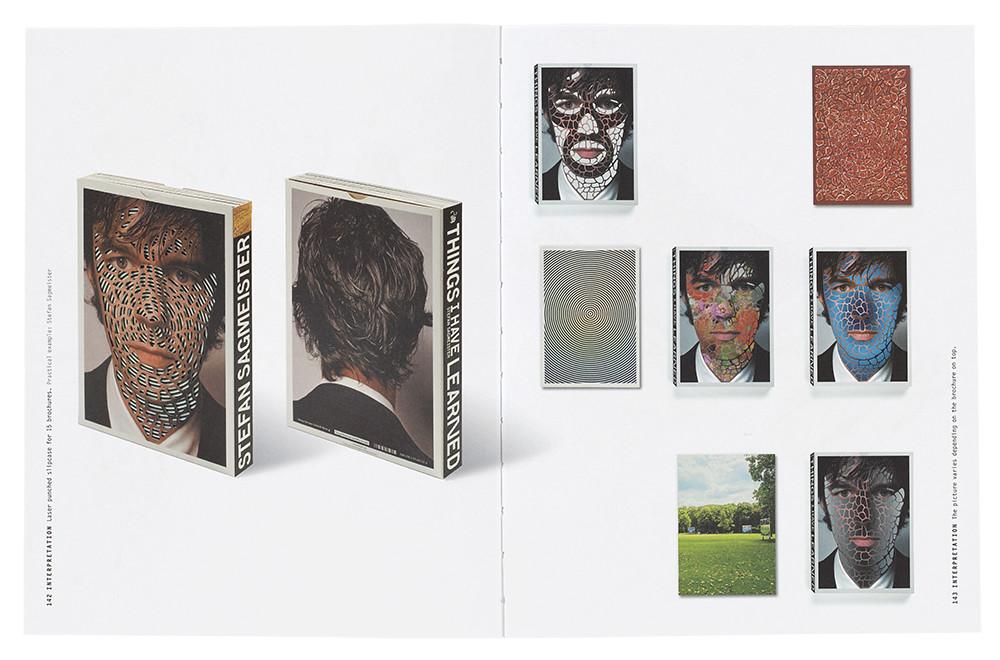

Expanding a visual vocabulary: Psychologist Rudolf Arnheim wrote in A Psychology of the Creative Eye that ‘All reproduction is visual interpretation’. Designers research and communicate by expanding a visual vocabulary, within which the content-related component always becomes visible. This is demonstrated by the adaptability of Stefan Sagmeister (on the cover and slipcase of his 2008 book Things I Have Learned in my Life So Far).

Design theory as practice

Exploring the experimental design process of Lindauer and Müller is both familiar and exceptional.Each page of their 2015 book Experimental Design engenders a slow-burning sense of revelation that nothing is new but everything is new. The premise includes invention and development, but it is the layering of content that reaffirms and reveals a depth of understanding about the creative process seldom articulated so clearly in a visual format. From the beginning, Lindauer and Müller implore the reader to experience the carefully constructed flow of ideas in sequence, especially if they are students and beginners. The sense of linearity feels important because the lateral connections and visual rhythms on display are intrinsic to the fluid relationship between system and play being explored. Experimental Design communicates its core ideas by being idiosyncratic, selective and adaptable in a first-hand example of design theory as practice.

While Lindauer and Müller refrain from making predictions about how design processes and education will continue to develop, their project seems perfectly attuned to a culture that is increasingly embracing convergence and interdisciplinary thinking. Lindauer talks about ‘disruptive innovations’, when an idea breaks free of convention while providing a purposeful direction to evolve further. This way of thinking applies to the development of ideas beyond visualising concepts on the drawing board. What Lindauer and Müller propose is that all designers and artists recognise their new definition of the experimental concept – to place a method of evolving creativity at the core of teaching and practice to help art and science become fully reintegrated within 21st-century design.

Images: spreads from the book Experimental Design: Visual Methods and Systematic Play (Niggli Publishing, 2015) by Armin Lindauer and Betina Müller. See niggli.ch

Kevin J. Hunt, university lecturer and writer, Nottingham

First published in Eye no. 95 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 95 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.