Monday, 1:33pm

9 February 2009

Advertisers in the dock. Again

Advertising is infantile, so banning ads aimed at under-12s will never work

The Children’s Society published the results of its Good Childhood Inquiry last week – its findings being, in summary, that the modern child is a miserable, godforsaken little tyke, mainly because of a materialistic adult culture, writes Robert Hanks.

The report has several suggestions for improving matters, including a ban on all advertising aimed at the under-twelves, as well as no TV ads for alcohol or unhealthy food before the nine o’clock watershed, when all the sex and violence is let out. Superficially, it’s an attractive idea but what would be the point?

Ads aimed at children are already banned in several countries, including Sweden (surely no surprise), and Jelly Helm, the adman turned critic of consumerism, is among those who have called for the US to follow (see Emigre no. 53). The idea of a ban doesn’t seem to have much traction in the UK, where commercial children’s television is already under threat; but junk-food adverts are already banned during programmes that might appeal to the young – an almost limitless category. The reasoning behind such bans is clear enough, with a variety of studies suggesting that children learn brands and brand loyalty from the age of two, that they don’t distinguish between adverts and programmes, that children who watch more television want more of the stuff advertised . . .

I don’t dismiss any of this.

Yes, adverts stick in children’s heads: I can still sing jingles or recite entire scripts from ads I saw in my youth – aliens laughing at our primitive Earth method of mashing potatoes, Godzilla-like monsters discovering that Chewits are even chewier than a 15-storey block of flats, Weebles wobbling but not falling down.

And yes, pester power is a genuine problem: as a child, I tried to use it to force my parents to get things I’d seen on television; as an adult I have struggled hard against my children’s desire for Cheestrings – an appetite based, as far as I can tell, entirely on its TV image rather than on how the revolting stuff tastes.

But if I had to list all the things that warped and buckled my character in childhood, it would be a long, long time before I got to the ads. Parents, meanwhile, always have the option of saying no, and it’s no good trying to pass the buck to advertisers, whose power fades to nothing beside peer-pressure and childhood crazes that defy commercial sense – a lust for Barbie today is replaced next week by a yearning for conkers, or a fad for wearing odd socks to school.

And segregating children’s advertising is impractical, for two reasons.

First, given the tendency of ads to colonise every space in the culture (see Rick Poynor’s ‘The Whispering Intruder’, Eye no. 29 vol. 8), you can’t ever hope to shield your children from them – not without withdrawing into Amish seclusion. Since children are going to have to navigate this world at some point, they may as well get started early, before they have money of their own to blow.

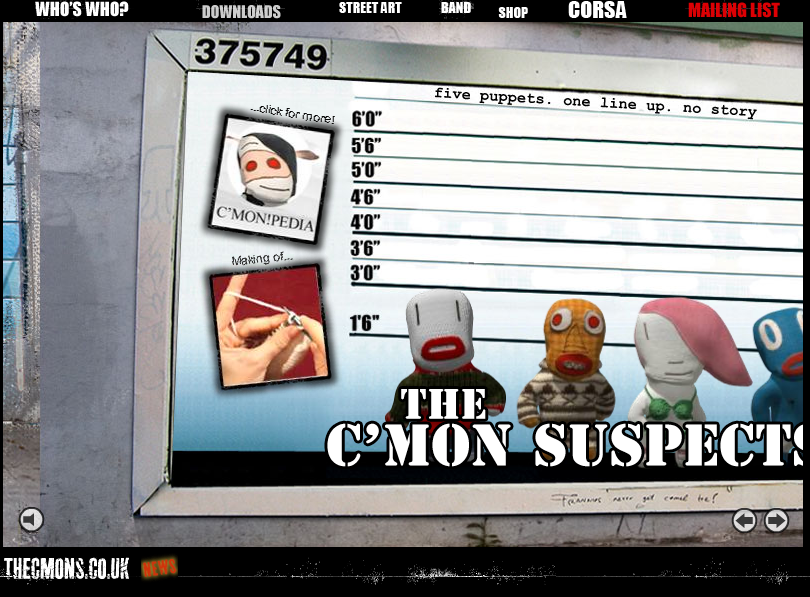

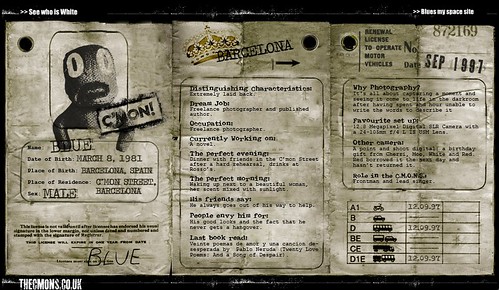

The second reason is that all advertising is, at bottom, infantile, directed at our inner child, the part of us that reacts to big, shiny things by shrieking: ‘I want it! Gimme!’ Sometimes, the tendency is more blatant than others – viz, the cuddly toys shouting ‘C’mon’ in ads for the Vauxhall Corsa. Abolish ads that appeal to children, and the only weapons left in the advertisers’ arsenal will be bald price comparison and barefaced sex. That’s a world I don’t want to pass on to my children.

Above and below: work from the ‘C’mon’ campaign devised by Delaney Lund Knox Warren.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.