Monday, 1:00pm

17 July 2023

Nothing is real

Wave: Currents in Japanese Graphic Arts

6 July – 22 October 2023; Japan House, 101-111 Kensington High Street W8 5SABad is the new good. Quentin Newark descends into Japan House for ‘Wave: Currents in Japanese Graphic Arts’.

Visiting, you descend stairs, like going into the Underworld, writes Quentin Newark.

The exhibition is about 60 artworks, ranging from little oil paintings to vast digital prints. They call it ‘graphic arts’, there is no typography, it’s all illustration, image making: pictures.

I attended an introductory walk-around, some of which I understood. Some of the phrases that came up during the introduction were about Japanese visual artists discovering the ‘super real’ and the ‘surreal’.

There is one image near the entrance, a painting done from a photograph, of tourists beneath a sunlit castle wall. Apart from that one image, there is absolutely nothing realistic in this exhibition, no image of the world as it is, no landscapes, no conventional portraits. This dimly lit exhibition is like one long dream-nightmare, hallucinatory, irrational, crazed.

Almost the only piece about the real world: Untitled by Megumi Yoshizane. My guess is this is Himeji castle, with its various shapes of musket ports.

Top. Eye by exhibition designer Yoshida Mayu representing the one thing tying all these artworks together, they are made with the use of, and looked at by eye.

Looking back on the introductory talk, I think they were trying to explain how modernity has wrought its effects on the Japanese psyche. In some ways the effects have been the same as here in the West, in other ways uniquely Japanese.

Since the Second World War, Japan has been subject to the same irresistible pressures most countries have experienced: booming economies, an explosion in technological development, accelerated urbanisation. Traditional ways of doing things, traditional clothing, architecture, picture-making, so important in Japanese culture, were mostly swept aside. The products of the West, from artistic movements to superhero comics to hamburgers, poured in.

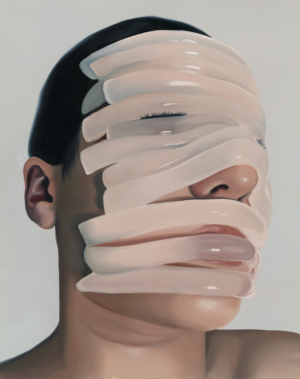

slime LXXV by Tomozawa Kotao. Her work features faces of dolls and young people smothered by disgusting substances; paint, glue, oil.

In a way this exhibition could be seen as a cataloguing of the longer term effect of all that. No-one is unscathed. Every human depicted in this show is troubled, they are suffocated by plastic tubes, they sob in anguish faces covered in mascara tears, they are possessed by foxes, sit naturally but without a face, or have their eyes sprout orchids, turn into a doll, or become a puff of gas ready to disintegrate. Humanity is not ok.

There are traces of traditional Japanese culture here and there, a Noh mask, a hachimaki headband. Otherwise, like in most Western visual culture, the past has disappeared, to be replaced by aliens, cyborgs, cut-ups, mashups, amalgams, surreality.

Giant blow-up of a drawing by Terada Katsuya, also known as Doodle King, very much in the charming soft-pencil curved-hatching style of Moebius (Jean Giraud). Every Katsuya piece is an explosion of complexity, and takes ages to look at.

Each image has its own style, another distinctive trait of our times. Anyone creative must find an identifiable idiosyncratic style, a visual world they can own, that we can know them by. (In the words of Khloé Kardashian, it’s your all-important ‘personal brand’.)

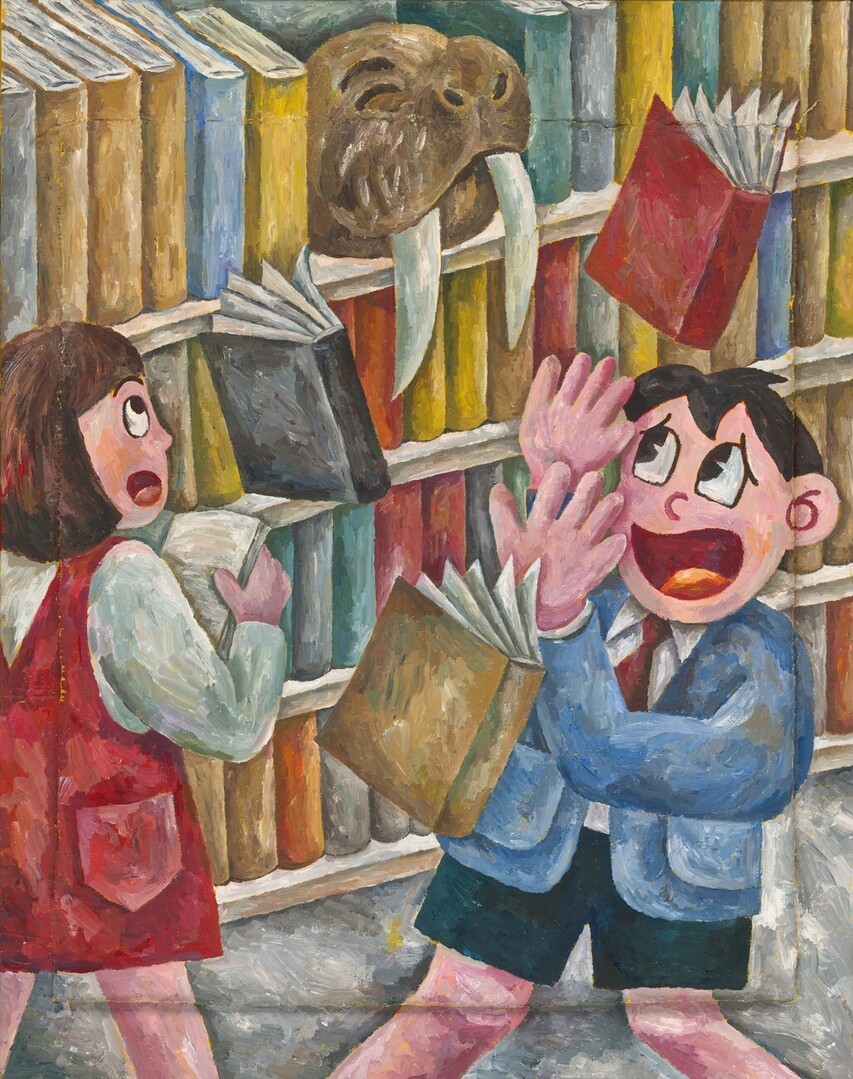

The main curator, Hiro Sugiyama, wanted us to know about ‘heta-uma’, which translates as ‘bad but good’. Meaning a clumsy style, but good ideas. (There is also ‘uma-heta’ meaning slick style but bad ideas, and ‘heta-heta-uma’ meaning really crude execution but strong concepts.) The advent of this approach, which began in manga comics in the 1970s, seemed to liberate Japanese visual culture, perhaps a bit like Pop Art opened infinite new artistic possibilities in the West of the 1950s and 60s.

Visitor looks at a strange end-of-times image by Moriguchi Yüji-Wall. In a quarry, schoolgirls armed with clubs threateningly confront the viewer.

The Walrus from the Bookshelf by Suzy Amakane. Like all the artists in this exhibition, Amakane draws manga, creates adverts, teaches, works as an illustrator. He typifies heta-uma, clumsy technique but powerful ideas. Why a walrus? Surrealism.

By the way, I could see nothing but consummate skill everywhere. (Can any Japanese person ever do anything poorly?)

My favourite pieces were Tanaami Keiichi’s montages, cut-ups of a comic about a Tarzan or Mowgli-like boy cavorting with a tiger, defeating dinosaurs and evil skulls. The posters swirl with clashing fluorescent colours that vibrate and almost seem to move.

Shonen Tiger by Keiichi Tanaami, recalls Roy Lichtenstein in its love of comics, glorying in print-screen dots and uninhibited bright colours.

This exhibition is a tiny sampling of what is out there. It would appear from this sample that Japanese visual culture is burstlingly alive, freed of any constraints. Style is wide open, content can be whatever, the only limit is how fast you can produce the outpourings of your fevered imagination.

There is no unifying thread to the works, other than that they are all by Japanese artists.

Quentin Newark, designer, writer, co-founder of Atelier Works, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.