Friday, 11:15am

28 June 2013

Two sides of propaganda

A new exhibition recounts the history of political persuasion, from coins to tweets.

The British Library’s exhibition, ‘Propaganda: Power and Persuasion’, shows a 1982 political cartoon that was drawn shortly after martial law was imposed in Poland. The drawing is of General Jaruzelski, a Polish political leader, attempting to bridge the gap between two sides of a widening chasm. The left side represents propaganda; the right represents reality, writes Katy Canada.

Politicians and the media continuously straddle the line between propaganda and reality because they must carry out the requirements of the community, and to some extent, manage a personal agenda.

From the coins carried by citizens of the ancient world to the most recent manifestations, this exhibition traces propaganda through decades of war, politics, tyranny, religion and discovery, proving that when it comes to political posters, health-related advertisements and social campaigns, an effective design can provide comfort, impart fear, or generate contempt.

An example of early propaganda: Napoleon portrait, 1813, by Jean Baptiste Borely © British Library Board.

Top: Freedom American-style, 1971, B. Prorokov.

The word propaganda, or propagate, was originally coined by the Catholic church. As media outlets proliferated and literacy rates began to rise, people developed an appetite for news, thus, accepting the word of the Catholic church as the truth. The church appealed to the interests of this specific sector of society, exploiting the desires of the public to serve a different cause.

Following the First World War, propaganda took on negative connotations. The term carried an implication of corruption and falsehood. The British Library’s exhibition points out that since that time, the perceived meaning of propaganda has been moved away from its true definition.

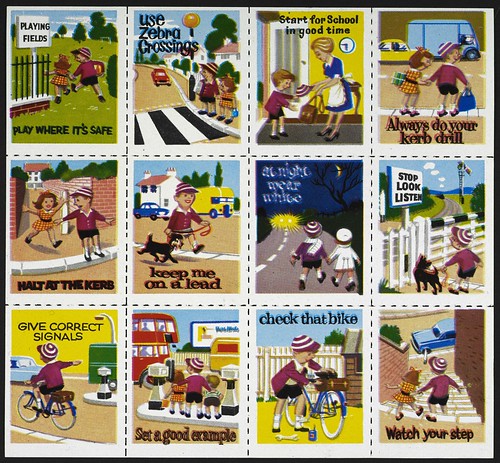

For example, positive propaganda may use selective information to gain support for a cause that would serve the public interest. The exhibition showcases the Tufty Club Safety Sheet from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) as an example of propaganda promoting a cause that is in the public interest. Paul Rennie wrote in Eye 52 that the RoSPA posters were produced during the Second World War, when finances were extremely limited. Rennie said, ‘Their messages recognise the radical potential of ordinary people to effect social change – something that was identified by Antonio Gramsci during the 1920s and 30s, and then espoused by George Orwell in 1941 as a necessary, but insufficient, condition of victory.’

Tufty Club Safety Sheet from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents.

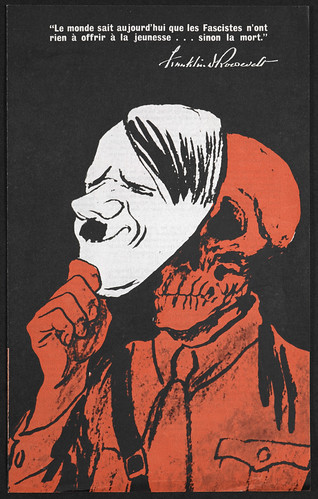

Propaganda has undeniably been used to blame the issues of a nation on a subsection of the population, often defined by race, religion, politics, social class or culture. This tactic used imagery to divert criticism away from political failings. Minority groups represented as monsters and thieves created contempt within a broad spectrum of the population. During wartime especially, states use propaganda to preserve morale at home, demonise the enemy and win support.

Franklin Roosevelt’s Message to Young People, an anti-fascism illustration from the Second World War, is an image of a skeleton holding a mask of Hitler’s face. At the other end of the spectrum, illustrations with similar styles and themes single out the Jewish community and other minority groups. Posters such as, Behind Everything: The Jew transmits a message that everything wrong about society can be pinned on a specific ethnic group.

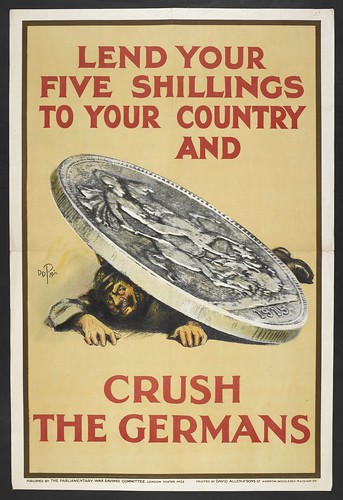

Lend your five shillings, 1915, Parliamentary War Savings Committee.

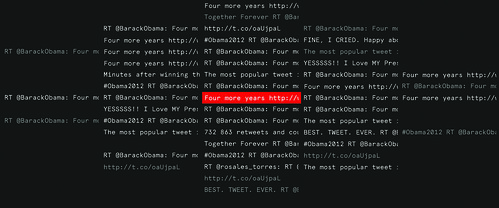

The final piece in the British Library’s exhibition is a digital collage of tweets composed after the election of President Barack Obama in 2012. This installation shows the way digital technology has created alternate platforms for propaganda in the 21st century. With new ways for people to challenge the state as well as communicate ideas, everyone is a potential propagandist.

Chorus, media installation (2013), is a visualisation of how news and propaganda spread across social media.

‘Propaganda: Power and Persuasion’ continues at the British Library until 17 September 2013.

Katy Canada, FIE undergraduate and Eye Intern

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 85 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.