Winter 1995

Archive: International Picture Language

Otto Neurath’s 1936 book was the fullest exposition of his vision of an international visual language

Otto Neurath’s postcard-format 118-page International Picture Language, published in London in 1936, turned out to be his fullest exposition of Isotype. This was the approach to visual representation that he and a group of colleagues had begun to develop at their Social and Economic Museum in Vienna from 1925 onwards. The work, especially after the German artist Gerd Arntz had joined the museum in 1928, shows the best characteristics of between-the-wars Modernism: great visual clarity at the service of meaning and social change, concern to spread information and to enable dialogue between citizens. When the brief civil war of February 1934 closed down democracy in Austria, the Neurath group left hurriedly for The Hague.

Already in Vienna, Neurath had made a contract for the production of two books with the polymath C. K. Ogden, who among many other things had edited the first English translation of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. The first book, Basic by Isotype, was an exposition of Ogden’s reduced, more efficient system of language: Basic English. The other part of the deal was to be an explanation of Neurath’s Isotype, written with the 850 words of Basic English.

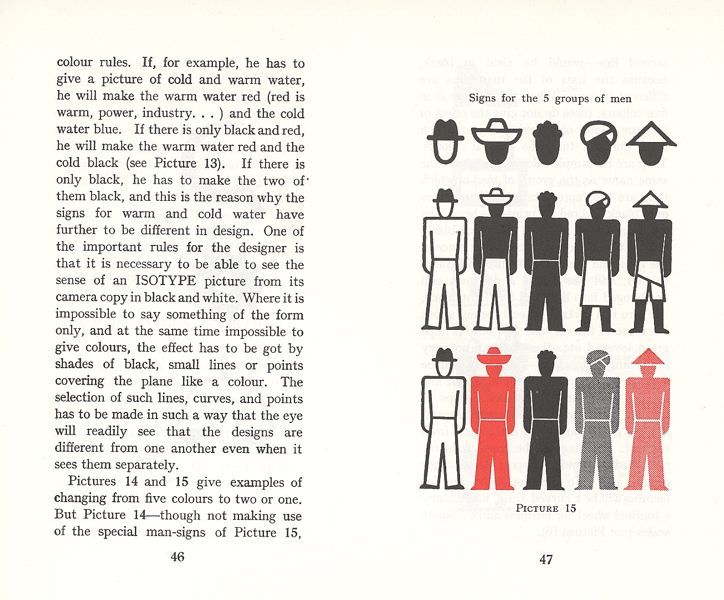

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936. Top. Close up of the chart presenting new representation of different races featured in the book.

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

International Picture Language has a utopian vision of an internationally effective system of visual language. As well as its part in twentieth-century Modernism, Isotype claims allegiance with Egyptian hieroglyphics, Comenius’ Orbis Pictus, and the great heritage of scientific illustration, map-making and explanatory imagery of all kinds and from many cultures. Visual presentation, Neurath suggests, can help us to transcend national barriers. ‘Words divide, pictures unite’, his slogan ran.

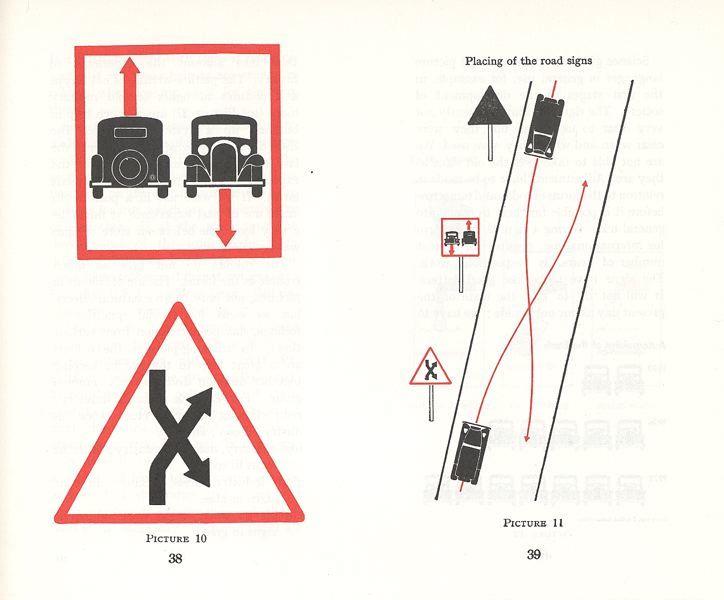

Otto Neurath was a pragmatist, an opportunist, and International Picture Language shows these qualities clearly. In its pages we find proposals for the use of Isotype symbols in public signing. This was merely a speculation by Neurath, but was taken up in earnest after 1945, the year of his death.

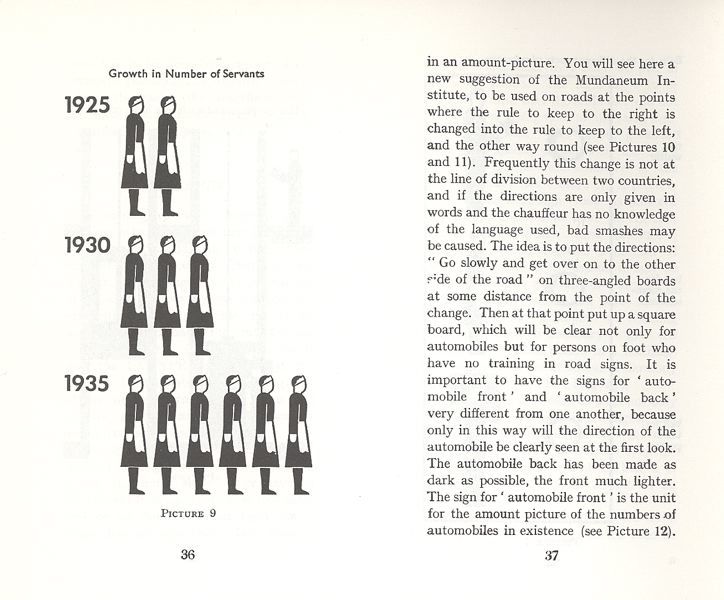

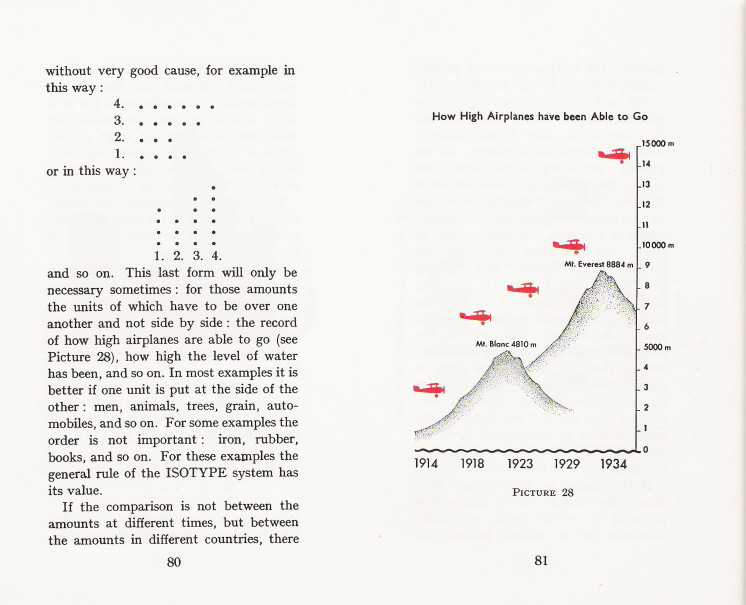

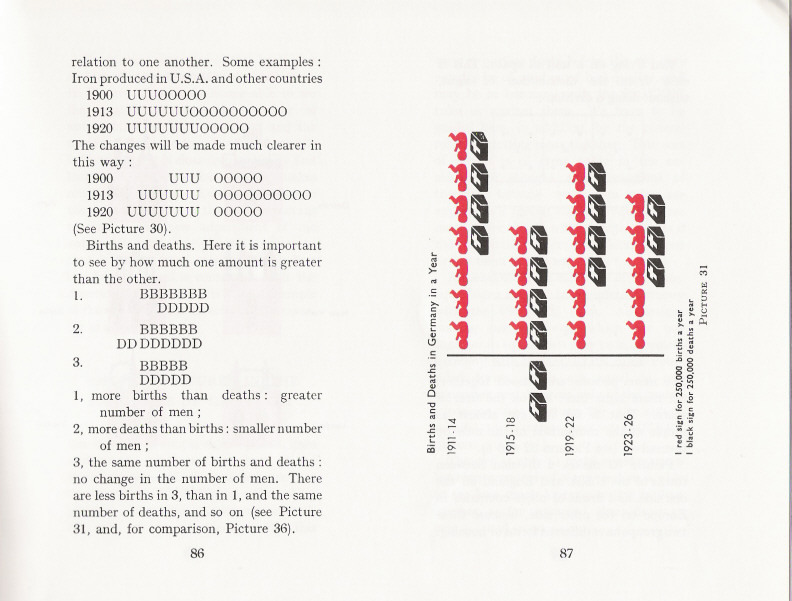

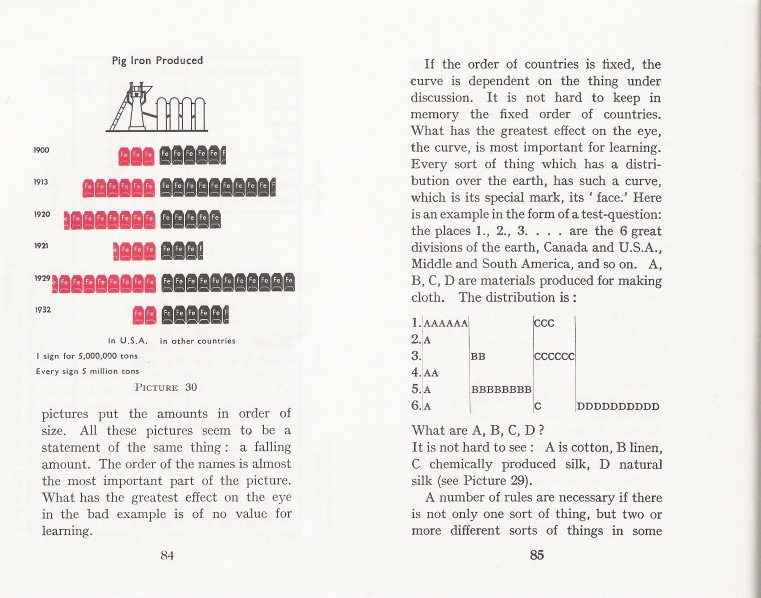

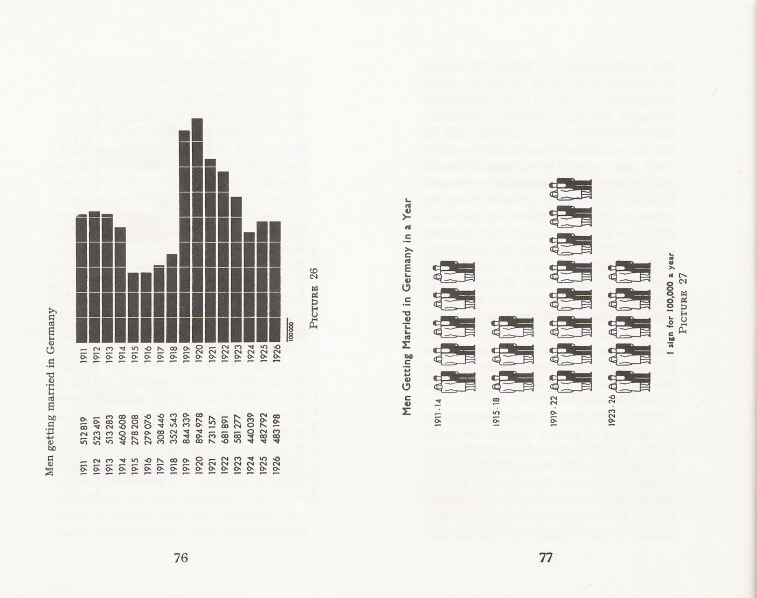

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

Although Isotype has been seen as totalistic and naïve, Neurath is always qualified in his arguments. Words are never banished. Pictures are there to help. The attitude is flexible and exploratory. He certainly makes great claims for the possibilities of Isotype. But this is the talk of a freelance fighter for a better world – he worked outside the academy – hoping against hope that the bomb clouds could be averted. When the German forces invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, Otto Neurath and his closest colleague, Marie Reidemeister, jumped aboard a lifeboat at Scheveningen, eventually reaching England.

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

What lives on in this book? Working your way through the strange deformations of Basic English and the sometimes touching antiquity of the images, you find things that must be pertinent, still, for any designer. For example: the continuous line of a graph (‘curve’ in Basic English) tells an untruth. We have only isolated data: so show those, as discrete bars. Or, how to order a set of quantities? By size? But then you only see the same story: increase or decrease. Better to find another principle of order: perhaps time or geography. Design a system that will let the material speak for itself. Above all there is the founding idea of Isotype: in representing quantities, repeat a unit, don’t enlarge it. Don’t say more than you know.

Isotype stands firmly in the tradition of Enlightenment Modernism. It was guided by meaning, rather than by predetermined form. Its reductions were at the service of freedom and enlargement. If it wanted system and standardisation, that was no more than a syntax with which fresh meaning could be made and shared.

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

Spread from Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

Front cover of Otto Neurath’s International Picture Language, 1936.

Robin Kinross, designer, design writer and publisher, London

First published in Eye no. 19 vol. 5, 1995

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.