Summer 2010

Interview with Dan Fern

Professor Dan Fern explains his pioneering ‘MAP / making’ course at the Royal College of Art, London

The extra-mural ‘MAP / making’ course is a collaboration between the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. MAP stands for ‘Music, Art and Performance’ and the programme brings together a group of students from both colleges who elect to work together for six months on projects for a variety of real-world commissions. To date the MAP / making programme has made work for Bath International Music Festival, London’s Southbank Centre, the Aldeburgh Festival, the Barbican Centre and many other clients and commissioners.

The course was originally designed by Dan Fern, who has just retired as Head of the Department of Communication Art and Design, and Head of School of Communications on 2 July this year. The MAP / making initiative was inspired by his own experiences in making collages and animations for a performance of new music by German contemporary composer Detlev Glanert, which Fern found to be a stimulating creative process: ‘We both felt that the film and the music belonged to each other in a symbiotic way.’ Fern decided that his RCA students would benefit from an educational programme that encouraged similar kinds of cross-platform collaboration, so MAP / making launched in 2000.

Eye: How many students take up the MAP / making option?

Dan Fern: In an average year we get fifteen RCA students and ten to fifteen Guildhall students. The RCA students are a mixture of illustrators, graphic designers and sometimes film-makers, video people. The musicians are a polyglot group of composers and instrumentalists. One of the interesting things for us has been learning to work with this strange group of people from different creative cultures who don’t know each other, to form them into a working unit that can make creative work together and be committed to each other and work collaboratively towards some sort of performance.

So we might have a really odd line-up of instrumentalists. It could be something really weird like five cellos, trombone, electric guitar and marimba – you couldn’t make it up sometimes. Then three or four composers, who might range from having a mixture of formal classical training in writing contemporary classical music, through to someone who’s a sound musician, an electronic composer. Adaptability – both for us, the tutors, and the students – is one of the main qualities that is required.

When we start the project it is characteristic of the music students that they can do one thing very very well. They’ve done it since they were kids playing an instrument, they are wonderful at it, but their general cultural knowledge is fairly limited – they know very little of the visual arts. And then the art students – their knowledge is very broad, they can make lots of connections between different world cultures … jazz, hip-hop, and rock … they can connect those things together. But they tend to have a rather horizontal and shallow knowledge.

You have these completely different mindsets coming together. One of the things we had to deal with right from the beginning was how to bring everyone up to a basic level of awareness of what each other was bringing to the process.

So one of the most interesting parts of the whole project every year is when the artists show what they do to the musicians and talk about how they make pictures, and what motivates them and where their influences and inspirations come from. Then the instrumentalists introduce their instruments, talk about how they work, physically, and how they came to be playing it … and play a short piece on the instruments, and then sometimes play together.

Eye: How many teachers or supervisors are involved?

Fern: Typically three of us from the RCA and three or four from the Guildhall School. We have learned on both sides that there will be strong students who you know straightaway are catalysts – somehow they only have to be in a group for things to happen around them. You can spot them. So you always try to manage it so that each working team has one of these people in it who are natural generators of ideas. That happens on both sides. In an average year we’ll get between 20 or 30 artists and musicians. We get something like six months to research an idea – often the performance is to communicate some sort of idea or narrative.

There is research time and there’s time when artists and musicians start experimenting together and workshopping ideas to see how the images and music can be brought together in this symbiotic way. The idea is always to find a symbiosis of the two processes where neither is relegated to the background.

Eye: Is this done entirely in workshops, or is there a didactic element?

Fern: There’s a didactic element in that quite a lot of the people who sign up have never worked in time-based media before, so they have to learn some of the technical processes that are necessary. One of the things we found to be very important from the beginning was that there needs to be some subject matter, otherwise the whole thing is too wide open.

‘On the Edge of Life’ (2006) was commissioned by Joanna MacGregor, the artistic director of the Bath International Music Festival. The theme was the vulnerability of babies, just prior to birth and just after they are born in different cultures – quite a hard subject to tackle. All of the students went to the premature baby unit at St George’s.

Eye: This thing of always working with a brief is food and drink to a designer or illustrator, but not so much for musicians …

Fern: No it isn’t, and they find that very interesting. You just mentioned the word illustration, and quite a lot of what we’ve done is an extended version of illustration – except instead of having a single person, the reader, and an object, we’ve got a performative work and an audience, quite often still telling stories or still making polemics (about the environment or climate change or whatever) but the theme and the way in which we present it is illustrative, and sonic as well, of course.

Eye: Is the principle of illustration embedded in this?

Fern: Yes, although I think it has to change radically when it’s put into a physical space with a live audience. Which has always been one of the main aims of the course, to work in a physical way.

I have always been very keen to make the whole thing experiential in a physical sense, that you work with real people in real spaces and you take what you produce into real spaces in front of live audiences, so that it is taken away from the virtual world that seems to be encroaching on so many other aspects of what we do.

Eye: Of course musicians, however narrow their outlook, have to deal with these real spaces all the time!

Fern: Absolutely. And it is interesting to watch musicians become part of the visual experience – wrapped up in cords, and in awkward situations where they still have to play.

Eye: But is there something innately conservative about musicians?

Fern: So much of music education has been geared towards providing people for the orchestras to play the classical repertoire.

Eye: A vocational education?

Fern: Yes, but professional life has changed for everybody in the past ten or fifteen years. Once you’d learn something at college and there would be a career waiting for you in that particular area – all of that’s blown wide open as you know. One of the reasons why we changed the whole make-up of Communications at the RCA was because the professional world into which students were graduating wasn’t linear any more, so we have to produce people who were adaptable to any circumstances. MAP is an exemplar of producing people for whom flexibility and a sort of creative ad hoc-ism are the core skills. They have to be technically able, that’s the bottom line really, but they’re intellectually adaptable and able to cope with any situation and learn fast and learn on the job and do it wonderfully well. That whole process mirrors the breaking apart of the old relationship between education and professional life, which used to be linear and related directly to the old discipline boundaries: if you were a graphic designer you graduated in graphic design. It’s not like that any more.

Eye: Has music education got to grips with this?

Fern: They’re coming into it slowly … The Guildhall has been leading the way in opening up the range of possibilities that are available to musicians by engaging a group of tutors who came from lots of different backgrounds, from jazz and from improvisation and electronic music. Their influence has filtered into the teaching programmes and certainly made it possible for us to do the sort of work we’re doing.

Eye: Would it have been possible at another college?

Fern: It would have taken more time.

Eye: Do you know of other initiatives like MAP / making?

Fern: Not quite like it. One of the reasons I’m keen to keep it as an element in the programme at the RCA is because I think we’re well ahead of the field.

Eye: Is this something that you could expand, or should it remain an extra-curricular thing?

Fern: We’re faced each year with a whole range of problems. We never know who’s going to sign up for the programme. There’s the budgeting problem. The art students and the music students have their own curricula to follow so there’s a scheduling problem. The venue is always different – it can range from a Gothic church to the Southbank Centre to a bandstand in a park! But having to accept that that’s our venue and being able to adapt to the circumstance is great. Quite often the venue has limited availability: we have to get into a space, set up, perform live to a paying audience and get out – within 24 hours. It’s one of the things rock musicians are used to, but art students and classically trained musicians are not, so they have to learn to adapt to it and enjoy it.

Eye: Would you like to do more with the programme?

Fern: Yes, but I’m not sure what my successor [Neville Brody, who starts in January 2011] is going to make of this. We’re at the point where there’s a changing of the guard. However I’m keen to keep it going in some form. In fact I would like it to become a two-year postgraduate programme. Imagine coming to London and spending two years working with visual artists and musicians – what could be better? It depends a lot on the financial situation: it’s the worst time in decades to be proposing new courses.

Eye: Apart from it being a stimulating experience, why should students spend their time and money doing courses such as MAP / making?

Fern: Well, the range of professional opportunities is much greater than when we started.

The number of people who have taken the MAP / making programme and who are now working in that field is starting to increase – there are professional outlets for what we do.

Eye: What kinds of work?

Fern: The obvious one is music and arts festivals all over the world. A lot of that is site-specific, another area where we’ve become quite skilled. Then there are all the exhibitions and trade fairs and conferences … corporate events, closer to the design industry or advertising world.

Eye: There is an argument for saying that the way things are presented now – any performance, whether it’s a concert or a trade show or a conference – you can’t not communicate visually, even if you have a stage full of musicians who haven’t even thought about it.

Fern: Well the idea that there are people who are trained specifically to work in that way, and where the music and the images are so closely joined because they are developed side by side – that’s a comparatively new thing. You rarely see any work of real intelligence linking the two areas.

Eye: Historically, might this be similar to the time when the role of the graphic designer emerged to liaise between the printer and the client?

Fern: That’s an interesting point. Could be. Its possibilities as a catalyst are enormous. Another area where there’s a lot of work is in ‘outreach programmes’. A lot of people who have worked in MAP / making have gone on to lead workshops in schools and hospitals and community groups and sporting events – there’s a whole range of different things available. It’s not simply about people who can create beautiful work in concert halls. It’s about all of the things education should be about over and above learning a trade. A lot of education is quite rightly vocational, it prepares people for the world of work, but it can lose sight of some of the wider ideals of what education should be.

Eye: Yet this kind of cross-disciplinary education seems entirely relevant to the way the world is changing. Could that be the most vocational thing you can do?

Fern: Yes, I believe that very strongly. It’s so easy to produce work which is technically impressive. With a laptop and software you can do amazing-looking things. What that leaves, as the real skills for the twenty-first century, are the skills of judgement, and being able to express ideas and articulate ideas, and to engage people and make them want to work with you, because technical ability is something that’s so easy to come by.

Eye: Why did you decide to get involved in music?

Fern: For me, music is the most important artform. It’s the one thing you find wherever you go in the world – music is the real internet. And an art school without music is not a proper art school!

However there are traps that you fall into when you try to put images and music together. Over the period of a particular performance, you want the two things to appear as partners. The questions are: did it tell the story, did it bring the two things together, did it entertain? However challenging the subject matter, it should be enjoyable and entertaining and it should push the audience a bit. Too many audiences are too passive and they need to be poked a bit.

Eye: Given the changes at the Royal College, what do you think will become of the course? And what will you be doing next year? Are you going to relax?

Fern: No! I’m working with two former students, Sophie Clements and Toby Cornish, on a big multimedia installation commissioned by Joanna MacGregor for an event at the Royal Opera House in September. Both Sophie and Toby – especially Sophie – have been closely involved in developing MAP. I’ll carry on being involved at the RCA for a while, supervising research students, for instance, and with any luck I’ll carry on with the MAP /making project.’

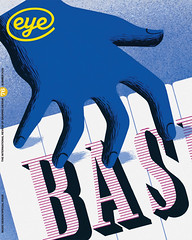

First published in Eye no. 76 vol. 19.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.