Autumn 1990

Official anarchy

For seventy years the PTT has been an exemplary patron

‘The government’s printed matter is ugly, ugly, ugly - thrice ugly - ugly in typeface, ugly in typesetting and ugly in paper.’ That no such condemnation may be made today of the graphic output of the Dutch postal and telecommunications authority (PTT) is due almost entirely to an innovative approach to commissioning and design pioneered by Jean-Fraçois van Royen.

At the time of his complaint in 1912, van Royen was only a legal clerk to the PTT’s board of directors, but he counted among his friends the leading architects and applied artists of the day. In 1920 he became general secretary of the organisation and thereafter employed the talents of Holland’s modern movement to revolutionise the design of everything from buildings, vehicles and furniture to letterboxes, letterheads and postage stamps. All this was done not only with the aim of improving the image of the organisation, but also to enhance the service for the customer, the working conditions of the employees and the environment in general.

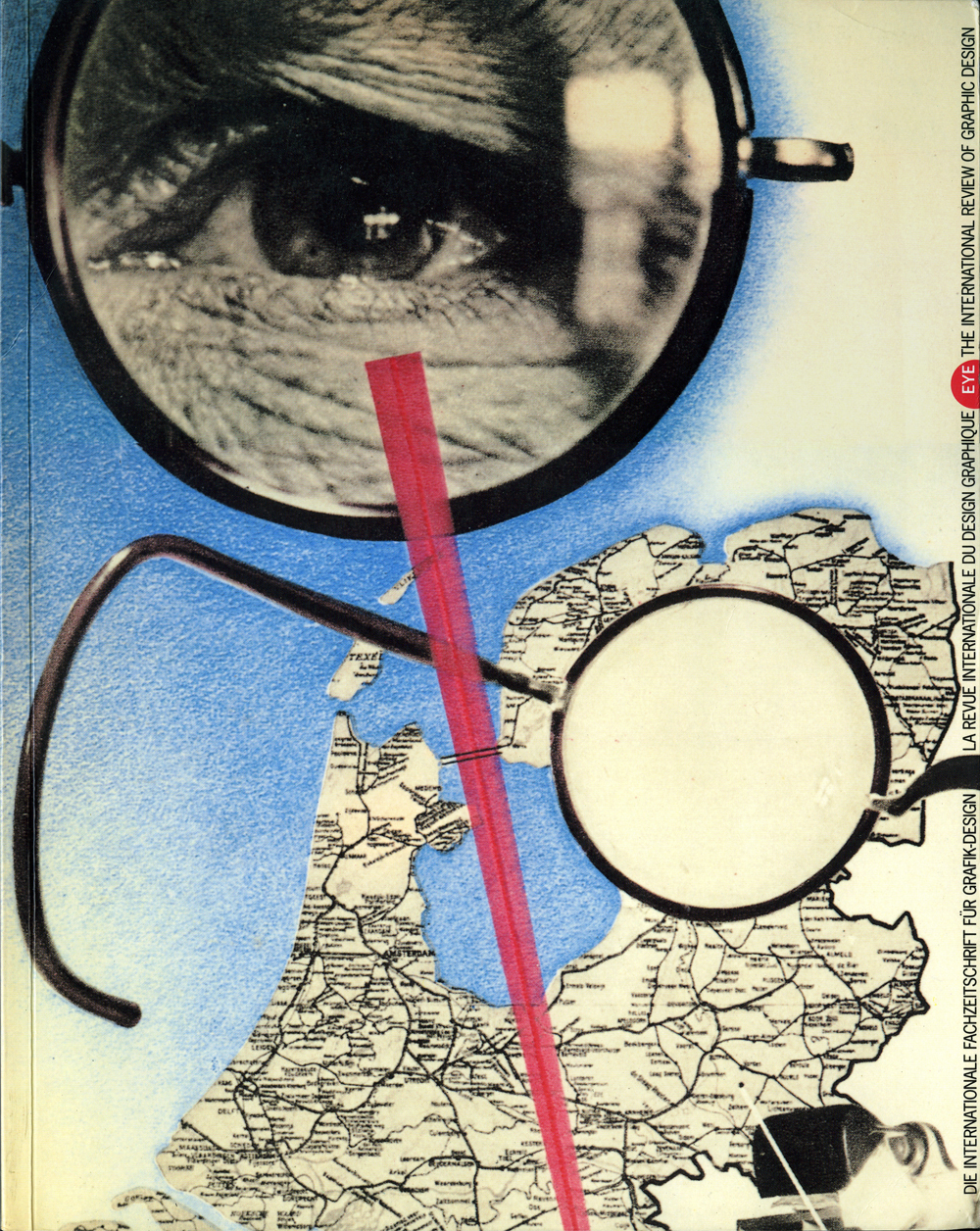

Van Royen himself was a master typographer, in the tradition of William Morris, Cobden Sanderson and his fellow countrymen Sjoerd de Roos and Jan van Krimpen, but despite his own strong views, he had an open mind when it came to commissioning others. He believed that a high standard of graphic was more important than a unified style, hence the PTT’s printed matter in the 1920s and 1930s is a catalogue of the different trends in Dutch design, from the decorative expressionism of the Amsterdam School seen in the work of Chris Lebeau, through Jan Toorop’s exotic brand of Art Nouveau to the dynamism of the ‘new typography’. It was van Royen’s consistent employment after 1929 of Holland’s champion of functionalism, Piet Zwart, and his colleagues Paul Schuitema and Gerad Kiljan that aroused most criticism, courting cries of ‘official anarchy’ from the national press.

Zwart’s typographic career had begun in 1920 when, at the age of thirty-five, he designed a letterhead for the Stijl architect Jan Wils, in whose office he worked. In 1923 he became friendly with El Lissitzky, who taught him the techniques of photograms and photomontage, and the inventive body of work he produced in the late 1920s gained him the admiration of, among others, Hannes Meyer, who invited him to teach at Bauhaus in 1930. His links with the European avant-garde were further strengthened when he joined Kurt Schwitter’s Ring neuer Werbegestalter, which included Jan Tschichold, László Moholy-Nagy, Karel Teige and Friedrich Vordemberg-Gildewart. For the PTT, Zwart designed posters, postage stamps (the first to utilise photography), leaflets, exhibition stands and a children’s book which explained the postal and telephone services in a highly original blend of free typography, staged photography and vivid pencil drawings.

The designs of Zwart’s colleague, Paul Schuitema, are much less refined. He found the scale stamp design difficult and the poster produced to accompany his stamps was much more successful. By far the most accomplished of the group’s stamp designs for the PTT was Gerard Kiljan’s 1931 set, which carried a surcharge in aid for disabled children. This annual series had in the past shown lively, healthy babies, and approach which to Kiljan spelled hypocrisy. His depiction of children with various handicaps caused a national scandal.

Kiljan devoted much of his time to his students at the Hague Academy, where, with Schuitema, he ran a semi-official course in advertising design. Of these students, dubbed the ‘maniacs’ by their critics, one of the most talented was Henny Cahn, who in the late 1930s made two brochure for the PTT in which he combined phototypography with pictograms and inventive cuts and folds in the paper.

The Nazi invasion of Holland in May 1940 put an end to experiments in the graphic arts. Van Royen formed an organisation to unite all Dutch artists against the invaders; in 1942 he was arrested and murdered in the concentration camp at Amersfoort. Following the end of the war the PTT established a department of art and design, which initially pursued a cautious artistic policy, attempting to repair the damage of the war rather than to pursue originality for its own sake. Among other developments, an informal school for stamp designers was established to promote more traditional skills such as portrait engraving and calligraphy.

After a change of leadership in the early 1960s, the department disbanded the school and used the money made available on experimentation with new techniques. Many of the stamps issued in this period are characterised by a new objectivity, as exemplified in the work of Wim Crouwel, co-founder of the multi-disciplinary studio, Total Design, in 1963. In a world growing more complicated by the day, Crouwel called for a ‘simplification of communication’ unhindered by emotional or expressive elements. Sanserif typefaces and geometric abstraction were combined with flat areas of colour to give a highly structured whole that found its parallel in minimalism and conceptualism in the plastic arts.

By the late 1960s there was a re-emergence of a collage-based phototypography and a more socially committed stance. Politicised by the revolutions of 1968 and the artistic movements of the radical avant-garde - Fluxus, Situationism and the Dutch provos - designers such as Jan van Toorn began to see Crouwel’s standardised, objective approach as a political cop-out. Every element in a van Toorn design - composition, colour and typography - is loaded with ideological symbolism. A good example is his 1980 postage stamp, in which the conservative politics of the statesman P. J. Oud are illustrated through his positioning, the blue background, and the rightward march of the word ‘nederland’.

Van Toorn has influenced two generations of young Dutch designers, most notably the collective Wild Plakken. A literal translation would be ‘mad collage’, though the term is used more commonly to mean illegal fly-posting. The group, consisting of Lies Ros and Rob Schroeder, works exclusively for cultural and left political groups and refuses to touch advertising. Their ‘hands-on’ method stems from their days as student activists, when leaflets and posters had to be produced as quickly as possible and where the most sophisticated equipment available was a photocopier.

Though the polarity between the formalism of Crouwel and the more political approach of van Toorn has set the agenda for Dutch graphics over the last twenty years, there has also been room for individual experimentation. Mention should be made of Dick Elffers, Otto Treumann, Jan Bons and Jurriaan Schrofer, all of whom have added to the diversity of Dutch graphics with their idiosyncratic styles. Some of the most controversial designs have come from Rotterdam-based Hard Werken, whose wilful eclecticism has no Dutch precedent, but has more in common with recent British graphics.

The present aesthetic advisor to the PTT is Ootje Oxenaar, a remarkable individualist who readily admits that he has designed very little in his forty-year career. Early collaborations with an ageing Gerrit Rietveld were followed by a number of stamp commissions, including the first computer-generated designs in 1970. Between 1965 and 1985 Oxennar was responsible for the design of Holland’s banknotes, and this, together with a professorship at the Technical University of Delft, has given him an enormous influence in Dutch cultural life.

Since 1980 the graphics section of the PTT’s department of art and design, which deals with postage stamps, calendars, diaries, stamp yearbooks, annual reports and special publications, has been headed by curator and design historian Paul Hefting. Hefting has pursued a commissioning policy of which van Royen would have been proud, favouring no one school over another, entertaining the traditional and the unconventional and employing painters, sculptors and architects as well as illustrators and graphic designers. Acutely aware of the dangers of relying on established names, he keeps his eyes open for emerging talent in his capacity as external examiner for a number of art schools.

The successes of the art and design department have always been hard won, and since the PTT was privatised in 1989 they have had to fight even harder against a drop in standards. In van Royen’s day aesthetic decisions were based on an ideal rather than on market forces or any vague notion of ‘public taste’. This year has seen the launch of a set of van Gogh phonecards calculated to appeal to touristic sensibilities – designer phonecards in the sense of designer water or designer jeans.

This is only one instance of bad taste within the PTT, but it is a commercial gimmick that Oxenaar would once have been able to resist. In five years’ time he will retire, leaving a position for which there is no obvious candidate. Will the PTT be able to sustain a remarkable seventy-year tradition of enlightened commissioning and design? Or will it fall back into blandness and indecision that characterises the design of so many similar organisations in Europe?

First published in Eye no. 1 vol. 1, 1990

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.