Summer 2022

Reputations: Garry Fabian Miller

‘I decided photography had to be colour when I was sixteen years old … The materials were difficult, but Cibachrome has this incredible colour saturation and permanence.’ Interview by Grant Gibson. Portrait by Philip Sayer

Garry Fabian Miller is a singular fine art photographer, who has established a reputation over nearly four decades making extraordinary photographic prints without a camera. He created them in his darkroom using just light and Cibachrome, a dye-destruction paper, and exposures that could last between one and twenty hours.

He was born in Bristol in 1957, the son of a professional photographer. He started taking socially engaged portraits while still a teenager; in 1974 he made a study of the Shetlands community, followed by the series ‘Sections of England: The Sea Horizon’ in 1976. His first solo exhibition was at Bristol’s Arnolfini Gallery in 1979. He moved to remote Lincolnshire in 1980 and began exploring ‘camera-less’ photography a few years later. Since 1989 he has lived and worked in Dartmoor, Devon, and his work has been exhibited widely – to great art-world acclaim. Miller’s photographs are held in many collections, including those of the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

Miller had already achieved some success with more traditional landscape works when he started developing his camera-less process in the mid-1980s. Initially he, placed plants into the head of his enlarger and shone light through them on to the paper. Later, he began to experiment by replacing the plants with glass and liquids, creating hugely colourful abstract images that have drawn comparisons to the work of Mark Rothko.

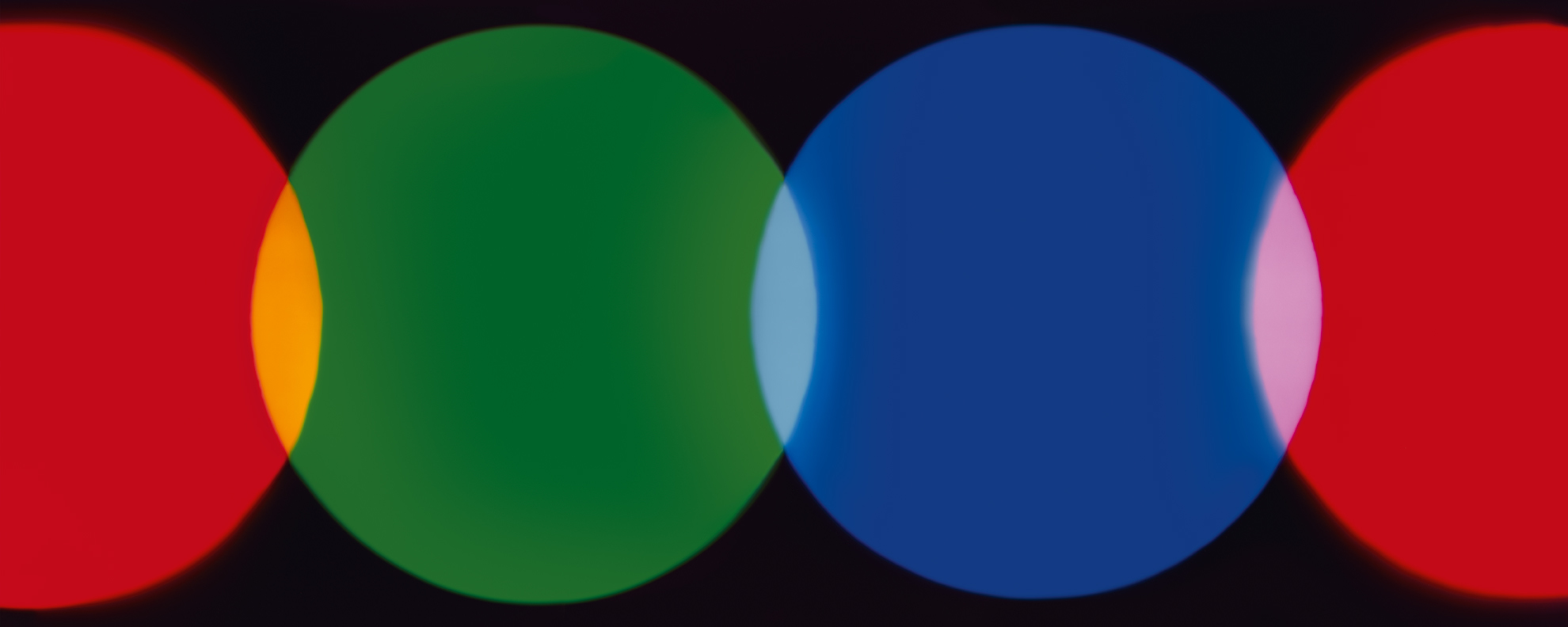

Our Big Dream, 2015. Top. Portrait of Garry Fabian Miller by Philip Sayer.

However, in 2012 the manufacturer of Cibachrome announced that it would cease production, bringing his craft inexorably to a conclusion. Miller was able to continue this working method by using up his existing stock and buying remaining materials from wherever he could find them, but meanwhile he investigated digital equivalents to the chemistry of Cibachrome. At the end of 2020 he called time on his darkroom practice. Miller has also expanded his output, using his photographic work as a basis for making rugs and tapestries, as well as working with musicians and poets on performance-based pieces.

This interview took a sharp turn into unexpected territory. We had been chatting amiably for 40 minutes or so when Miller delivered a stunning, harrowing piece of news. The subject of his studio’s closure had been broached and, when I asked if he felt a sense of bereavement, there was a pause in the conversation: ‘Right, Grant, I’m going to tell you something. I don’t want to go too big on this but it’s quite important. In December 2020 I was diagnosed with bladder cancer and that’s why I walked out of the darkroom. What is apparent is that it has been caused by the Benzidine in the Cibachrome. I am one of the last people who’s spent 50 years, almost every day, exposed to this in a Victorian shed-type environment and it has caused me to develop this cancer and it’s going to kill me. So this whole end story is deeply tragic … The end of the darkroom is basically the end of photography, which is a noxious, dangerous industry. I’m a casualty of it.’ The craft that dominated Miller’s life and art will be responsible for his death.

The diagnosis has accompanied a remarkable burst of activity. Miller is making the most of his remaining time. There will be major shows next year at the Arnolfini in Bristol; in Oxford; and at the National Museum Cardiff. He has written Dark Room: A memoir, to be published by the Bodleian Library in 2023, which will feature an essay by author, artist and potter Edmund de Waal. And Miller has just been awarded an honorary fellowship with the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, during which he will deliver a public lecture series ‘The Light Gatherers’, which began in March 2022 and runs until October.

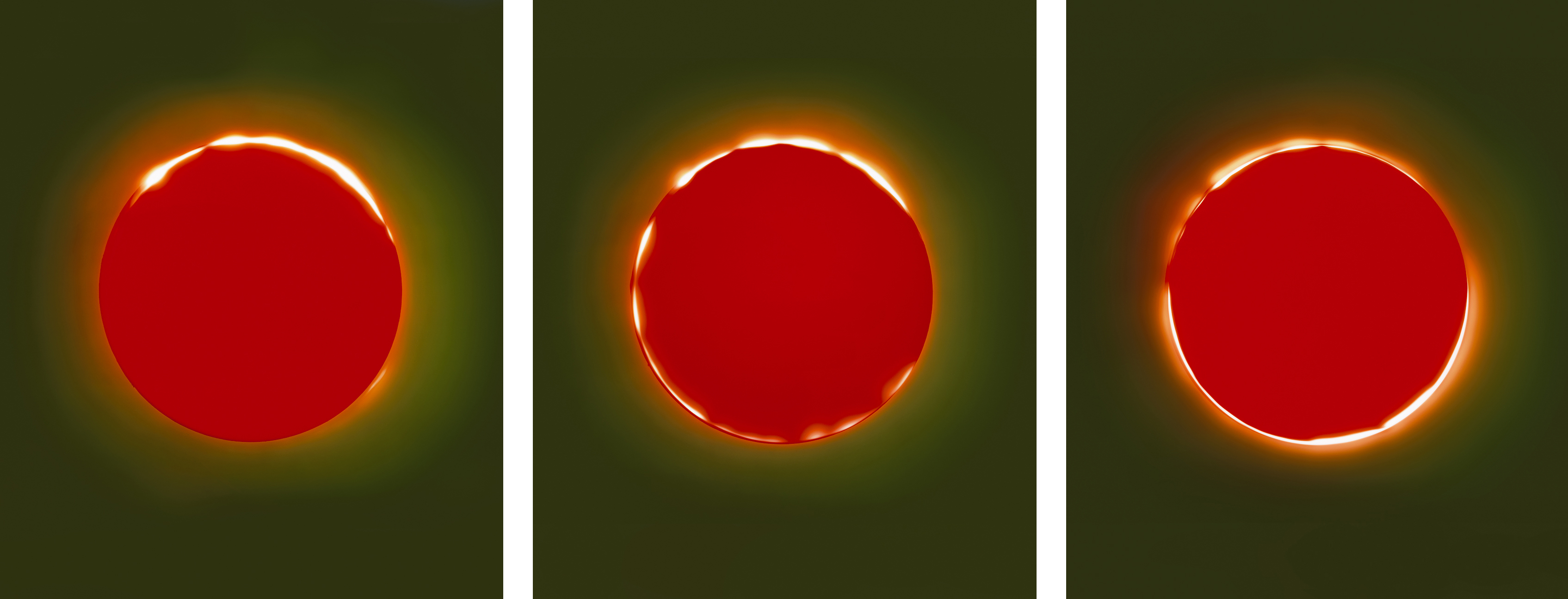

Colour Seed 08, 2001.

Colour Seed 09, 2001.

Grant Gibson Can we start by talking about your honorary fellowship with the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford? How did that come about and what does it entail?

Garry Fabian Miller Richard Ovenden, who is Librarian at the Bodleian, approached me for a picture in aid of a fund-raising auction to acquire the Fox Talbot archive. We met at breakfast when I was in Oxford doing a performance event with the poet Alice Oswald. It transpires he had a passion for photography as a teenager – he wanted to be a photographer but lost confidence and trained to become a librarian instead. We ended up going for an hour-long walk after breakfast. He led me through the Bodleian and showed me where we could have a darkroom and where I could show films. Then he took me upstairs and pointed out the rooms that the fellows have and told me I could have one. In the space of 8o minutes, we’d gone from meeting to [my] being offered an honorary fellowship to explore the darkroom and photography. And this was purely because he has a passion and desire to make photography part of the culture of the Bodleian library. He wants to embed photography there and the collection to grow. It’s a wonderful, lovely thing. My fellowship is just another staging post. Obviously, he thought I can bring something that he feels the institution needs and, essentially, he wants the city of Oxford to become a centre of photography. It’s globally on the map as a place you have to go to study Fox Talbot and he’s trying to build out from that.

You’re going to be giving a lecture series there. Do you have any other responsibilities?

It was meant to happen a couple of years ago but then the pandemic arrived, and everything went into cold storage. The plan was that I would deliver six lectures on topics of my choosing. I said it would be about the darkroom, the end of the darkroom, and the darkroom as a site in the history of photography. Then I’m going to do masterclasses – though none are scheduled at present – for invited groups of people. I decided to do the lectures over two years, one in each term. I’m also beginning to do some research, which will feed into the lectures.

So the pandemic delayed the fellowship, did it affect your practice in other ways?

In the second week of lockdown, for some reason, I decided to go to my studio and start writing a book about my darkroom. I’d always intended to do it, but I thought if I could write this now, then it would work as an introduction to the fellowship. I wrote for the first twelve weeks of lockdown every day and I had a draft before Christmas. It’s a memoir and a life story. The Bodleian is going to publish it. There’s also going to be an exhibition of my work staged during 2023 in Oxford but that won’t be in the Bodleian. They’re going to hire a warehouse-type space instead. That’s because I said to them that, as part of the fellowship, I wanted to do some performance-related stuff aimed at young people, with Oliver Coates, a musician I’ve been collaborating with. So next year, there will be the book, an exhibition, and my final three lectures, as well as some other performance-y stuff in Oxford.

And the memoir, why did you decide to write it?

I’ve always been interested in books, and I just wanted to tell the story of a life lived in a darkroom, then present my work from that perspective. My models were those kind of books that are written from another perspective. The best example is James Rebanks, the farmer in the Lake District, who wrote The Shepherd’s Life, a diary about being a shepherd. I wanted to write a book about my career and show how you could make a life in this tradition. It starts off when I was a teenager and takes the reader through how my photographic world evolved.

Were you always destined to be a photographer?

My father was a photographer, so I was stuck in this darkroom because it was childcare in the school holidays, whether I wanted to be there or not. If he’d been a carpenter or a blacksmith, I’d have been dumped there instead. He developed wedding photographs and I realised quickly that I was seeing something miraculous happen, where something would appear from nothing. What appeared was mundane, but the process was transformative. I guess if you’d grown up and your parents were makers, say with clay, and you saw that same process unfold, the transformation with the kiln – and I compare the darkroom to a kiln – you’d get drawn into it. And then it was a question of what to do with it. I didn’t choose it. It fell into my life, and it seemed to have potential.

At that point the notion of photography as fine art was nascent I guess.

It was totally undeveloped. As a teenager I had no interest in what my father did – commercial photography. But photography, in those days, didn’t exist as fine art. And so my career kind of grew with the beginning of university courses and galleries showing photography. My life was changed by coming into contact with a scene – and that scene was the Arnolfini in Bristol, where I could go in as a fifteen-year-old and see art, which sometimes used photography. It was totally different to anything else I’d ever seen. There was early work by Richard Long, for example; there were constructivists from Europe. And these had a huge influence on me when I was fourteen or fifteen years old. It had a bookshop that contained a lot of political books, a number of books on feminism. The gallery suggested to me that there was some way that photography could have a bigger purpose than commercial practice.

And you went up to Shetland to take a series of images when you were sixteen?

That’s what you had to do. It was documentary photography rather than art. I decided to go to Shetland because there was a story about oil industry development. The other thing I did was work with Shelter in Bristol when I was seventeen, photographing homelessness for them to use in posters and publicity material. I was doing this like a teenager might photograph bands on a stage.

I used to hang out with Paul Graham at Arnolfini. In 1976 he set up a darkroom in his bedsit in Clifton and we would do our Cibachrome printing together. And then the gallery gave us a show. That was our first exhibition. Other images I’d taken got picked up by the Serpentine Gallery, and places like that, and suddenly you were part of something that wasn’t parochial life in Bristol.

Those were your ‘Sea Horizons’ pieces?

Yes, exactly. Suddenly I had the beginning of a career. My mother died at that point, and I knew I had to get out of this family business and escape. That’s why I went to Lincolnshire.

It’s an interesting move. You left a city where you were forging a career.

I felt I had to start again. I wanted to live a kind of life that wasn’t city life, and Lincolnshire was inexpensive. And, to me, that was as important as being part of the photography scene, which I’m not really that interested in. By doing that, I immediately separated myself out from Paul Graham, Martin Parr, Peter Fraser, all these people that were hanging out in Bristol. My community was somewhere else. It was a case of going out to the country to find out who I wanted to be and then figure out how photography sits within that. And it wasn’t easy for a few years because I really didn’t know what I was doing.

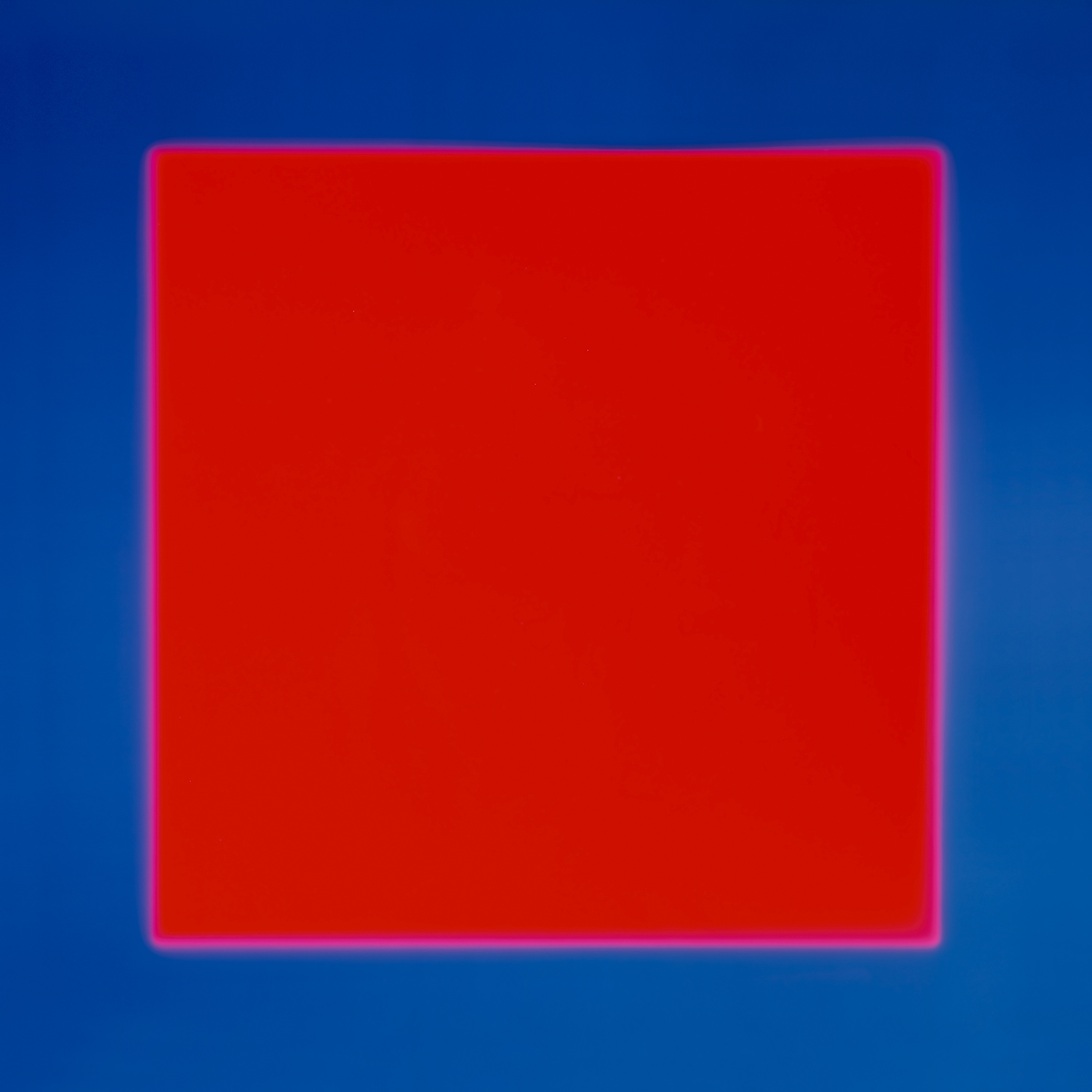

The Colour Field, Green Encloses Red, 2001.

The Colour Field, A fluctuating Blue touches the Red, 2001.

The Colour Fields, the Place where Gold and Pink touch, 2001.

Darkroom, the Yellow we Made, 2020.

The Colour Field, Black Ground, 2021.

And that was the time, in the mid-1980s, when you stopped using the camera. You’ve been quoted as saying that the camera was getting in the way. Why did you decide to do that?

I went off to Lincolnshire with a camera and printed my pictures in a darkroom. I spent a lot of time doing what I thought I should be doing, and it wasn’t going anywhere. There was a summer where I photographed wheat coming out of the ground in the fields surrounding my house. I was interested in the way the sun pulled the plant out of the soil and turned it green, and I used a camera to try to photograph this phenomenon. But then, I realised this is all so complicated and wasn’t at all the relationship I wanted. In parallel, I made a garden, and I grew plants. I had a personal relationship to them, and I observed changes. And I just thought: ‘Why don’t I just take the plant and let that be the transparency; place it in the head of the enlarger where the transparency would usually be; shine the light through it and let it make its image onto the paper.’ It worked. The camera has gone and now I have a direct relationship to the materials – to the plant, the light beam, and the photographic materials. Together we were trying to make images exist and permanent. The camera had become a complication. Then I spent five years trying to work out what to do with this method. I ended up getting a lot of commissions from the environmental charity, Common Ground, as well as the Southbank and the Department of Environment (DoE), who were looking for artists that worked with nature for the V&A exhibition ‘Artists in National Parks’ [in 1988]. A group of us were commissioned to do these exhibitions, including David Nash, Andy Goldsworthy and Helen Chadwick.

Can we talk about your interest in ceramics? You have quite a collection of craft, in general, but pots, in particular. Do you feel you belong in the craft world?

That’s my community. Over the years, I’ve built a community around writers, poets, and crafts people. It’s because, somehow, I feel our lives are more in tune than with photographers. I think it’s something to do with the making practice. I was trying to seek out people who had a way of making work that somehow replicated mine, although the materials were completely different. That’s how I fell in with potters. I’ve just written an essay about the potter, Richard Batterham, for a book to accompany his V&A show. It is really like a love letter. He became a hero for me in my late 30s. He was living the life that I was trying to live. I wanted to be in a rooted place making things, understanding how you make things, and becoming very good at it in that craft tradition.

You moved from Lincolnshire to Dartmoor in 1989. Why did you make that shift?

My work was in shows that were touring the country. Two or three of them arrived in Exeter where Naomi Fabian was a curator at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum. I met her, fell in love, and moved my whole life to be in Devon where she was. And from there, we’ve built our life.

Did Dartmoor change your practice?

It meant I was living a little itinerantly for a while. My darkroom was gone. I moved into her house, and I had to create a darkroom in a bedroom. I made work in the late 1980s in the most improvised conditions, but the tradition of darkrooms is a variation on a shed, that’s how they began, based around people mucking about with science and chemistry in sheds.

And your career is entwined with Cibachrome paper …

It’s 50 years with one material. I decided that photography had to be colour when I was sixteen years old. It was a big decision to make, as it was going against the tide. I was aware that colour photography was happening in the United States, and some of it was coming into the Arnolfini in group shows. The materials were difficult, but Cibachrome has this incredible colour saturation and permanence. So I decided to shoot on transparency because it has the most saturated colour, compared to colour negative. Then I had to use Cibachrome because it was the only positive-positive printing relationship. In those days, you could buy it in camera shops. It was a wonderfully seductive material. Basically I never stopped using it because I was happy and satisfied.

But it became a finite material?

Yes. And then it stopped. But 50 years is a good run. So I’ve lived with the end of the materials for a long time and then they ended. The last pictures were made in November 2020. There was a day in December when I walked out of the studio, and I knew I’d finished. The darkroom is the past. I don’t feel great sadness now. The last pictures were ecstatic, riffing on colour abstraction. I feel happy and resolved about how it ended: in a beautiful place.

Your relationship with digital repro specialist John Bodkin at Dawkins Colour has become increasingly important to your career as Cibachrome became harder to find.

I met John in 2006. He had made the leap from treating drum-scanned colour transparency film as the raw material of his craft to manipulating digital files on screen. I was introduced to him by production manager Martin Lee (ex-Omnific), who knew that John was developing an approach to photographing artworks and to processing the resulting digital files that would soon transform the quality of colour printing.

So how do you work together?

John and I began pooling our understanding of the ‘colour spaces’ of Cibachrome and chromogenic (C-type) prints made from digital files in 2009. We discovered that Durst Lambda printers – which focus images on to photosensitive paper with red, green and blue lasers, but then process them in a more traditional chemical system – have a colour gamut that can emulate the saturation of Cibachrome. In the first year we made just four pictures using this method but over the next twelve years we made 150.

Aside from the fellowship, there have been tapestries and rugs created around your work at places such as the Bristol Weaving Mill?

I knew the darkroom was ending, so I had to live with how to end it. I’m currently working on a project called ‘Three Acres of Colour’, which is about growing natural dyes and making colour from them. Projects like that are to do with the end of environmentally damaging production systems and trying to reconsider how we make everything. People describe it as a land art project. I’m also working on my third tapestry with the Bristol Weaving Mill, which will be shown at an exhibition in spring next year at the Arnolfini. I’ll be taking all of the galleries. It’s a survey of my life and the different themes within it, and will be entitled ‘Adore’. It will start with five or six of the Sea Horizons that I showed in 1979 and will include: the last darkroom pictures, a gallery devoted to craft, and another gallery about Dartmoor. We’ve got one year to deliver a show. It will also coincide with the Oxford show and the Oxford book. The Arnolfini is publishing a book too. Suddenly I’ve got this wonderful moment; it’s a wonderful story. But it’s a lot to do.

In the Green Darkness, Stars Bled, 2021.

The Breaking Storm, 2015.

A Lost Colour World, 2019.

Grant Gibson, design writer, editor and host of Material Matters, London

First published in Eye no. 103 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.