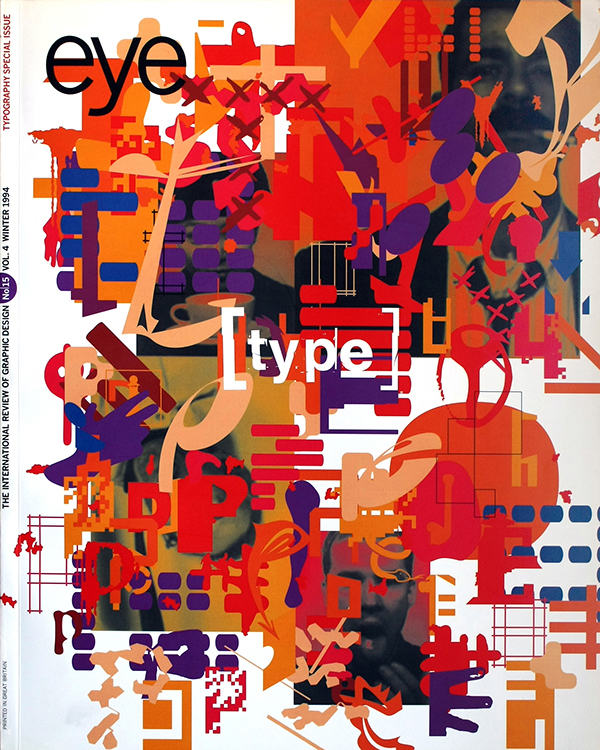

Winter 1994

Spot the difference

Mass-market style has created an audience with an insatiable appetite for more of the same

Mass-market graphic design is seldom looked at by design journals. Yet it is most ubiquitous style of graphics in the world: it could even claim to be the first truly international style. For many designers, it is the medium of our living rooms rather than of our studios or classrooms; the style that entertains us in private (ironically or not) as opposed to the ‘designer’ styles which we use to present our professional selves to our peers and clients. Or it is something we try to avoid altogether, retreating into the rarefied realms of good taste and ignoring a phenomenon that may account for as much as 70 or 80 percent of the publishing market.

The style of mass-market graphic design is anything but simple. Hectic, crowded, crammed with a wild array of colours and competing pictorial elements, it aggressively demands attention. Typographically, it cares nothing for high design's conception of taste or restraint. Where up-market and middle-market publications confine themselves to a limited range of typefaces, used in an orderly way, mass-market style resorts without inhibition to a babble of serifs, sans serifs and brush scripts. Type is condensed, expanded, underlined, set at excitable angles, placed in multicoloured panels, boxes and rag-outs for emphasis. At its most effective, the style contrives to be both noisy and legible, a kinetic enticement for the news stories, features and reader services it adorns. It is a style that promises the reader value for money.

Mass-market graphic design was born of capitalism, from the need for editorial to compete with the tricks of advertising; it has been nurtured by the growth of consumerism and is now the accepted style of many media forms in western culture. It began with the growth in newspaper publishing in the nineteenth century and the need for editors to deliver pages that could hold their own visually beside the woodcuts and fancy typography of the new display advertisements. During the twentieth century it has been developed by trade-house typographers and paste-up artists, mostly without the guidance of formal training or pretension, who punched out weekly tabloids and home journals to almost unchanged formulas, creating a seamless illusion of continuity through repetition. Design school-educated designers may now be involved in the process, but even today mass-market design is not so much produced as reproduced by production rooms within the large publishing houses which act as training grounds for the implementation of a house style aimed at grabbing the reader.

Mass-market style has created a mass audience with a seemingly insatiable appetite for more of the same. The emphasis is on presentation rather than content, the goal to maintain the market share for low-priced magazines and newspapers.

In the UK, the top-selling women's magazine is Woman's Weekly, with a circulation of 786,000. This, together with its closest rivals Woman (769,000) and Woman's Own (758,000), dominates the market and far outsells up-market monthlies such as Elle (223,000) and Vogue (183,000). And, as with the other highly competitive mass-market magazines, the TV listings guides, they share the same publisher, IPC Magazines. These big sellers are at times almost indistinguishable. Like rival brands of toothpaste, they compete forcefully while containing more or less identical ingredients packaged in more or less identical designs. The need to find the most compelling editorial hook leads to a predictable uniformity of content. The TV titles have been known to run exactly the same cover story, using photographs from the same shoot. Soap sells best and this was the soap opera cliffhanger of the week.

It is impossible to ignore the role graphic design plays in this colonisation of our lives by consumerism. In effect, graphic design has become the principal agent that ascribes value in industry and the media that serves it. Graphic signs, symbols and devices have been incorporated into a massive project of cultural engineering, a system whose purpose is to serve the competitive interests of industry, culture and media.

A simple binary aesthetic code has developed whose positive values are still based on the Modernist aesthetic of ‘less is more.’ ‘Pr-aesthetic’ design – the positive end of the spectrum – encompasses the bland neutrality of the academic journal or novel, design determined by the idea of type as a functional carrier of information. Like mass-market style, this type of design usually goes unremarked because it characteristics are familiar and user-friendly. Also encoded as pro-aesthetic design are styles which might at first appear oppositional, but in fact simply use elements from the contemporary canon of good taste to attract attention. The most admired publication in this genre – Interview, Harper's Bazaar, The Face, Arena – are deemed to represent the cutting edge of design, but for all their supposed risk-taking, they usually manage only to extend or enliven the code rather than to subvert or overturn it. Oppositional design is often merely hinted at by graphic elements chosen because they are familiar yet imply an awareness of cutting-edge challenge.

Mass-market

style occupies the other end of the aesthetic code – the

‘anti-aesthetic’ or opposite of good taste. Socially, this code

is used to distinguish one class from another and to reinforce the

values of the bourgeois-dominated status quo. The anti-aesthetic is

inherently an inferior position, delegated to the working classes who

are encouraged by its consistency, repetition and ubiquity to

identify as their own, enabling them to be aesthetically targeted and

manipulated by advertisers and consumerist interests. Graphic design

education views most fields of anti-aesthetic design with contempt,

leaving the publishing industry to train its own designers in the

subtleties of the codes it has created and understands.

Keith

Robertson, lecturer, Royal

Melbourne Institute of Technology

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.