Spring 2019

They made Canada

Working against the clock, with virtually no budget, Greg Durrell made a design documentary that shows how European immigrants created Canada’s visual identity

Greg Durrell’s Design Canada tells the story of the designers who created the visual identity of modern Canada. The 74-minute documentary is packed with vivid reminiscences, archive materials and plenty of detail about the sprawling country’s flag, railways, sign systems, institutions and sport. The film’s core subject matter spans approximately two decades, starting with the late 1950s ‘CN’ symbol for Canadian National Railways and reaching a climax around the time of the 1976 Montréal Olympic Games. Durrell, a first-time director, interviewed dozens of designers from this time, and the result is a coherent, entertaining movie that tells a story as little known in Canada as it is to the rest of the world.

Late last year, Durrell came to Zürich to introduce the European première of Design Canada, a good-natured gathering enlivened by the presence of Swiss designer Fritz Gottschalk (b.1937), one of many European designers who, as the documentary explains, made a crucial contribution to Canadian design and identity four or five decades ago.

The following day, Durrell was happy to chat about Design Canada over coffee and croissants in the spacious premises of Gottschalk + Ash International. He traced the movie’s genesis to a casual question that ‘changed his life’. Durrell had been working on the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics when a client asked how long the maple leaf had been a symbol of Canada.

‘Nobody knew!’ said Durrell. ‘I went to the library that day and looked it up. What started off as this little query grew … I needed to be in the room with someone who had created the Canadian flag. I followed my curiosity.’

Did he have a script for the documentary in his head?

‘I did have a few points,’ he said. ‘The flag emerges, the Expo happens, the centennial, but I didn’t know who the key players were.’ Durrell began his researches in 2011, but had little success in reaching veteran designers. Then, early in 2012, he heard that designer-illustrator Theo Dimson (b. 1930) had died. ‘I decided at that moment that I was not going to let another person pass away. I would begin to call myself a film-maker.

It was kind of a lie. I would call people up and say “Hi I’m Greg,

I’m a film-maker from Vancouver!”’

The committee of fifteen MPs assembled to decide on a flag for Canada in 1964, shown in Design Canada.

Top: Kramer (left) with Design Canada director Greg Durrell.

Luckily for Durrell, everyone took him at his word. Before long, he was on a mission, interviewing Burton Kramer, Stuart Ash, the aforementioned Gottschalk, James Valkus (a key person behind the Canadian Railways identity) and Heather Cooper, who designed the Roots brand, and provided an articulate opposition to what she calls ‘the great wave of rationality coming from Switzerland’.

Since most of the designers on his list were in their 70s, 80s and 90s, Durrell knew it was a ‘race against time’. (Several of the designers featured in the film have passed away since its completion.)

Walking on eggshells

Using his own money, and with the support of his business partner Ben Hulse, Durrell raced around Canada to interview designers about their recollections, taking a small bag with the equipment he needed.

‘I believe that those who travel light, travel far,’ he said. He prepared for his odyssey by researching DSLR cameras and lenses, usually using two set-ups: one wide, and one close. At one point he even Googled ‘how to make a film’.

Many of the designers he tracked down no longer spoke to each other, after disagreements over credits and other personal animosities. Durrell, walking on eggshells as he pieced together the story, appears to have achieved his goals through empathy (as a fellow designer), energy and unlimited good humour.

Slowly, he assembled a team. Gary Hustwitt’s documentary Helvetica had been an early inspiration. ‘Helvetica made me realise that design stories can be made in an accessible way so that someone like my Mom can understand what I do.’ Durrell contacted Hustwitt, who put him

in touch with Jessica Edwards, his colleague at Film First. Edwards liked the proposal and came on board as Design Canada’s producer.

Canada’s 150th anniversary in 2018 supplied a deadline, so they

set about fundraising. ‘This was a perfect time to analyse Canadian identity through the lens of the symbols that we use to represent ourselves,’ said Durrell. ‘Canada has incredible arts funding, so we thought it was a no-brainer.’

However all the arts funders turned them down.

‘The reasons were twofold,’ said Durrell. ‘One was that it was “design and not art”, so we didn’t qualify for arts funding! The other was that I was a first-time film-maker. We thought there would be support, but there was nothing.’ Durrell plugged on, spending his own money, and in 2017 he raised Can$99,000 through Kickstarter.

‘On paper that sounds great, but when you break down the cost in terms of producing all the rewards and the percentage that Kickstarter takes, the PR and everything, it doesn’t amount to a lot.’ But before long other supporters came along: Telus, a Vancouver-based telecoms firm and Ottawa-based Shopify.

Most of the funding was Durrell’s own cash. ‘I would work and save my money and use that to traveland collect these stories.’ Was he running on empty? ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘To me this was never about money. I wanted to watch this film.’

Heather Cooper talks about her designs for clothing company Roots in Design Canada.

One of the strengths of Design Canada is the way Durrell weaves together the personal insights and minutiae of the design story with the broader narrative of social and political change. Contemporary voices, such as author Douglas Coupland (‘postwar Canada was still Britain’s bitch’) and designer Marian Bantjes are also in the mix, and there is a charming interview with Massimo Vignelli, who shows with pencil and paper why the famous ‘CN’ identity for Canadian National Railways works so well.

In January 2018, Durrell screened his film to friends, who confirmed something that bothered him. As designer Diti Catona says in the film, ‘1960s design was dominated by European men.’ He hit on a solution: ‘Instead of the viewer telling me there’s a gender inequality problem,

I want to tell the viewer. I’m going to put the film critic in the film!

It was very scary to do this. I had to spend another few thousand dollars, the film’s overdue, we have over 1300 Kickstarter backers asking where it is … and I don’t even know if it’s going to work.’

Durrell hired journalist Hannah Sung to discuss issues of race and gender and immigration, and inserted her voice early in the movie. ‘There was only a certain kind of immigrant that Canada really wanted,’ says Sung. ‘It wasn’t a multicultural society.’

Happily, these last-minute changes worked well. Yet Design Canada is more than a series of talking heads. Durrell’s visual flair is evident throughout, from the sympathetic framing of his subjects (in close-up and wide shots) to occasional vistas that remind the viewer how beautiful Canada’s landscapes can be. He shows the work – the logos, posters, ads, flags, hockey sweaters and so on – and he uses a strict grid system to display information and inter-titles.

Social and political upheaval

The selection of archive footage is astute, with several clips that demonstrate how the visual expression of national identity –

in the choice of the flag and other symbols, and in the bilingual road signs – had a crucial role in bringing Canadians together at a time of social and political upheaval.

The musical score, using analogue synthesizer sounds and acoustic piano, drives the narrative with brisk momentum.

Though Durrell clearly admires European Modernism, he ensured that Design Canada articulates debates about design – about the wisdom of imposing design ‘from above’ and the place of ornament and beauty – that still rage today.

With this film under his belt, Durrell is keen to make another. ‘I’m glad I did it this way, because I got to experience all the different roles of film-making. Trust me, I made huge mistakes along the way!’

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

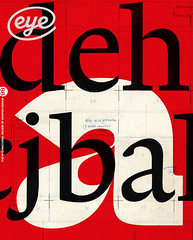

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.