Summer 2016

Time machine

Each summer since 1973, artist Tom Phillips has taken photos of the same twenty places in his South London neighbourhood. The resulting artwork – 20 Sites n Years – is both conceptual art and social history

Every year, artist Tom Phillips follows a carefully plotted nine-mile walking route around his southeast London neighbourhood taking photographs. It is the only time he ever uses a camera, and he has been doing it since 1973. The expedition is not undertaken for sentimental reasons (although the timing has a personal connection) and it is not for a photo album. The purpose of his journey is a work of art: 20 Sites n Years. And though the work began in the pre-digital age, shot on analogue colour film, it seems made for the 21st-century art world, digitally archived with an online slideshow and now – to Phillips’s surprise – even a hashtag.

Phillips (b.1937) is perhaps best known to graphic designers for A Humument, his ‘treated Victorian novel’ (see Eye 18), which exists in six editions and as an iPad app. However his extensive oeuvre embraces myriad elements: paintings, prints, video, portraiture, collage, sculpture, mosaics, found objects, several collections of postcards, public art, graphic scores, operas and the street lamps in Bellenden Road near his Peckham studio and home.

Sixteen of the twenty sites lie on a circle, half a mile in radius from the first, which was his family home and studio when 20 Sites n Years was devised. The other three sites are also former studios; they trace a path from the centre to the circle. Each picture is taken with the same camera and lens and film stock, from the same angle and at the same time of day. It is Phillips’s intention that the project will go on forever, continued by his son and other helpers yet unknown as the n in the title grows. This year, n = 44.

The work is a kind of system, or mechanism for making art. When I first encountered it, via a slide show that Phillips gave at Camberwell College of Arts close to where I live, it reminded me of George Pal’s movie of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1960), in which the actor Rod Taylor straps himself into a proto-steampunk contraption and watches the dials whirr. Buildings rise and fall, wars come and go. He ends up in the same location many years into the future. The ideas behind 20 Sites were partially echoed in another movie, Smoke (1995), directed by Wayne Wang from a story and script by Paul Auster, in which Auggie Wren (Harvey Keitel) takes a photo of his tobacconist store from the same spot every morning.

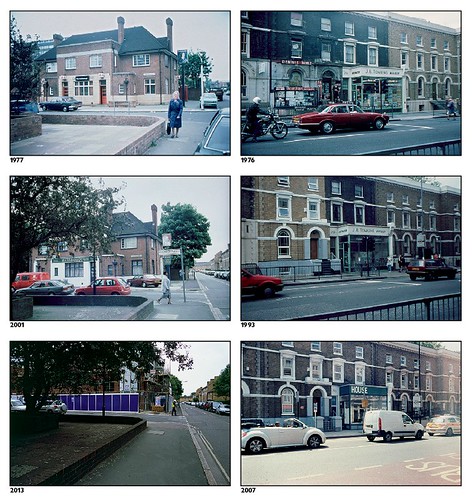

Right. Site 5. The Marlborough pictured in 1977 and 2001. By 2013, the pub had been demolished.

Far right. Site 6, originally the business premises of an eccentric local called Dennis Noble.

Top: Site 11. In the Camberwell housing estate. Site 15. The site named ‘Obart’ shows what began as a terrace in Wingfield Street, Peckham, half of which was demolished in 1975.

As Phillips’s images click by, you see changes both subtle and surprising. Beneath his camera’s dispassionate gaze a terraced house is ripped down and replaced by an inferior construction whose flaws become apparent with successive slides. In a tiny park, a brick wall is erected in front of the camera, only to slowly crumble away, aided by vandalism and neglect, until replaced by railings. The railings then disappear and a grassy space opens up once more. A tree grows tall and wild behind billboards. A local cinema becomes a multiplex, decays and disappears altogether – ironically, in British Film Year, 1985. Yet there is no irony in the pictures themselves. They are a clock, a diary, a record of time passed.

I first followed Phillips on his annual pilgrimage in 2012, watching him as he stood in the sun, squinting into the SLR camera he bought for the purpose back in 1973. He starts on his birthday (25 May) or thereabouts, and now – unable to encompass the circuit in one day – completes it over several; always shooting at the stipulated time. With the help of a bound and weatherproofed A4 book of maps, notes, diagrams and sketches, he frames each picture as closely as possible to its predecessor. Then he makes a mark on pavement or wall with a spray can to locate the spot for the following year.

The process of taking the pictures for 20 Sites n Years was originally prescribed in a two-page typewritten document as a conceptual or ‘land art’ piece (in the manner of Richard Long, the Boyle Family or Art & Language). Phillips specified a ‘Praktica 35mm LT camera with a semi-wide-angle Soligar lens plus lens hood’ and ‘Kodachrome X (ASA / BS 64: 19 DIN)’, which he subsequently had to replace with Kodak Professional Elitechrome Extractor 100 when the original film stock was discontinued. The artwork’s subtitle is Obart, taken from a sign over an arch in Wingfield Street in Peckham, site 15. But conceptual art is about more than ideas, it demands commitment, and Phillips has stuck to his plan. 20 Sites is another kind of human document, 880 ways (so far) of seeing the streets in which he has lived and worked for more than 50 years.

For the first quarter century of its life 20 Sites was hard to see – you had to wait until Phillips gave one of his entertaining slideshow performances. He published elegantly annotated extracts in his book Works and Texts (1992). Now you can see it on his website, tomphillips.co.uk. And though some might applaud the work for its conceptual purity, which might place it alongside Michael Craig-Martin’s An Oak Tree in the pantheon of 1970s art, there’s a ‘social history’ aspect to 20 Sites that makes it a curious record of changing times and patterns, buildings and people, the observations of a Rip Van Winkle who wakes up once a year.

Phillips sometimes talks about the views he selected for 20 Sites as having the ‘artless’ look of postcards, another of his enthusiasms as a collector and anthologist. His unpretentious pictures show many facets and moods of the area … quiet, busy, cluttered, peaceful, bleak. The imposition of a circular path on a rectangular grid – in which Victorian builders filled this formerly rural area with terraced houses – echoes the ‘systems’ music and art of the 1960s, in which Phillips was an enthusiastic participant and catalyst; he had acclaim as an experimental composer before he became known as a visual artist. The prescribed route has a pleasingly asymmetric rhythm, cutting across the physical and social geometry of the neighbourhood in a way one would never experience during a walk to the shops or school, or while commuting.

Phillips has turned the route-map into artworks, too: a version turns up on page 53 of the second edition of A Humument. The text revealed on that page reads: ‘The gallery of a hundred years, of a thousand, is in every street. Art in the street, covered deep with pictures vivified.’ A sixth and final edition of A Humument will be published in October to coincide with its 50th anniversary and some recently completed pages are on view at the 2016 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in London.

In recent years, the sight of Phillips, holding an SLR camera to his face, squinting into the viewfinder and squeezing the shutter button with a heavy clunk, could be regarded as a relic of the recent, pre-digital past. In his original instructions for 20 Sites n Years Phillips declared: ‘This equipment should be handed down with the assignment and cared for with a view to its lasting as long as possible. Even if the whole practice of recording images by such means seems ridiculous, antiquarian and quaint, the succeeding Artists are urged to eschew possible improvements and to carry on with the equipment given.’ However in May 2016 Phillips defied his own diktat, went digital and photographed the 20 Sites with a digital SLR, a Nikon d3300 with an 18-55mm AF-P VR lens.

‘There was a fork in the road and I took it – later than I should,’ he said, reflecting on the problems of obtaining film, and the repairs needed after someone dropped the Praktica. He had to make the rules flexible (‘as long as possible’) because he has always intended to pass 20 Sites on to others. When he says the pictures could eventually be taken by a robot and a drone, he is only half joking.

Over a drink during a break between sites, Phillips chatted about various different ways of presenting 20 Sites as a slide show at public events. ‘You can show the slides backwards, for example,’ he said. ‘That means there’s always an ending,’ I said. ‘That’s absolutely right,’ said Phillips, with a glint in his eye. ‘Of course it’s completely fucking obvious, but I liked the way you said it.’

John L. Walters, Eye editor, London

Read the full version in Eye no. 92 vol. 23, 2016

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 92 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.