Autumn 2013

Vapour trails

Steampunk’s florid industrial nostalgia might yet be the defining aesthetic of our time

Less than a decade ago, the idea of turning an unprejudiced eye on the abandoned design practices of an earlier century was sufficiently novel for Jessica Helfand to write an article on ‘The Shock of the Old: Rethinking Nostalgia’, in Design Observer (27 October 2005). The title proved prescient a year later, as interest in the fashions, technologies and overwrought aesthetics of the nineteenth century began to emerge not among designers but among science fiction [SF] writers and their readers. A genre usually concerned with the future turned its attention to the past as a new generation of authors picked up a minor SF trend from the 1980s called steampunk. Readers disposed to the dressing-up displays known as cosplay started arriving at conventions wearing flying goggles, top hats, corsets and other quasi-Victorian gear. There was a resurgence of popular interest in the kind of aesthetics that many would have thought left for dead after a century of Modernism.

Since 2006, the visual style has migrated from the science fiction shelves to infiltrate mainstream culture and fashion. The steampunks themselves have become a small, easily identifiable subcultural tribe; thanks to social media this evolution has been swift and international. So why is this happening now?

The current boom is situated at the convergence of several trends, the first of which has been a loss of faith in the predictive accuracy of science fiction. Or, as Paul Kincaid wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books (3 September 2012), ‘perhaps it would be more accurate to say that [SF] has lost confidence that the future can be comprehended’. Promised innovations such as artificial intelligence, mass robotics and space colonies have failed to materialise. The western world is now so resolutely post-industrial that the relics of the industrial era have gained exotic qualities. In an era of smartphones and computers whose non-moving parts are both invisible and inaccessible to the user, there is an understandable attraction towards the conspicuous components of clocks, early combustion engines and steam machines.

Cosplayer at ‘SteamCon II’, a steampunk convention held in Seattle in 2010. Photo: Jake Warga / Corbis. Fashion designer Andrew Dyrdahl at a Seattle steampunk exhibition ball, 2011. Photo: Jake Warga / Corbis.

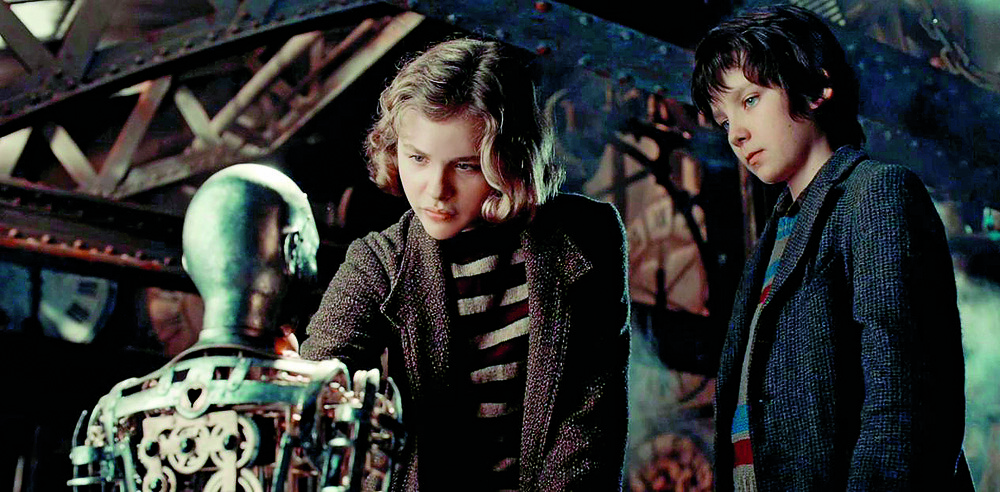

Top: Hugo (Asa Butterfield) and Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), in the film Hugo, 2011. Production Designer: Dante Ferretti. Director: Martin Scorsese.

Steampunk is a product of the 1980s, its name, coined in 1987 by K. W. Jeter, being a semi-serious rejoinder to cyberpunk, that decade’s vibrant SF subgenre. Where cyberpunk concerned itself with a near-future of global corporations and anarchic computer hackers, steampunk, in the novels of Jeter, Tim Powers and others, looked to the genre’s antecedents to play with characters and ideas from nineteenth-century novels. Science fiction had woken to a legacy of outmoded speculation that might serve as a resource for new ideas.

The most common of the early steampunk scenarios is the alternate history, an SF staple given a Victorian twist by Michael Moorcock in 1971 with his anti-imperialist The Warlord of the Air. In the novel’s version of 1973 there has been no Great War and the British empire still dominates much of the world with giant airships. In Morlock Night (1979), Jeter sends the Morlocks from H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) back to Victorian London after they capture the Time Traveller’s vehicle; in The Difference Engine (1990), William Gibson and Bruce Sterling temporarily left cyberpunk to propose a nineteenth century in which Charles Babbage’s (steam-driven) mechanical computer has already kickstarted the information revolution – 100 years early.

The initial excitement of written steampunk, for readers as well as writers, came with the novelty of seeing outmoded technology repurposed, and the realisation that the scenarios of Jules Verne, Wells and others offered undeveloped material.

Despite the early promise of its fiction, steampunk’s aesthetic qualities found more of an expression in film (The City of Lost Children, 1995), comics (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, 1999) and animation (The Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello, 2005). The subculture began to emerge in the US around 2006-07, and by 2008 was sufficiently established for The New York Times to pay it some attention. In 2009 the first ever museum exhibition devoted to the subgenre, ‘The Art of Steampunk’, opened at the Oxford University Museum of the History of Science.

Steampunk’s origins may be literary, but the visual style – the airships, complicated brass machinery and steam-powered robots – has no single source. In addition to derivations from the lavish covers of the Hetzel editions of Verne’s novels, the aesthetic combines decades of exaggerated details from sources as diverse as Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), the TV show The Wild, Wild West (1965-69), Robyn and Rand Miller’s Myst computer games, and numerous comics.

Ruth La Ferla’s New York Times feature ‘Steampunk Moves Between Two Worlds’ (8 May 2008) noted the importance of crafting and customisation among enthusiasts, who were creating their own clothes or fashioning antique façades for laptops and PC cabinets. Jake von Slatt (steampunkworkshop.com) is the master of the latter technique, with a prodigious talent for retrofitting bland computer components in hand-tooled brass and wood. The antique style of steampunk has proved relatively easy to grasp, and for those who like dressing up it offers a more inventive playground than the cosplaying at SF conventions, which tends to be restricted to copying characters from mass media.

The humble cog or gear has become the definitive steampunk motif thanks to its combination in a single object of brass (the essential steampunk material), mechanical engineering and the semiotic immediacy of a spoked and toothed circle. The simplest way to signify the subculture is by attaching dismantled gears or clock mechanisms to a piece of clothing or a poster design.

The 2012 Olympics opening ceremony, London. Designers: Suttirat Anne Larlarb and Mark Tildesley. Artistic Director: Danny Boyle.

On the design side, the florid and overwrought graphics of the late nineteenth century have emerged from their long perdition at a time when type foundries such as Jim Spiece’s Spiece Graphics (example: Zinc Italian SG) and Michael Hagemann’s FontMesa (example: Rough Riders) have been digitising Victorian typefaces.

Not all the print design is successful; some of it is little more than bad pastiche using anachronistic type styles or freeware fonts. However the better designs, as with Von Slatt’s retrofitting, take the best of the past and refashion it for the present.

My own involvement with the imagery of steampunk began in 2008, when writer Jeff VanderMeer asked me to illustrate his distillation of the subgenre formula:

‘Mad Scientist Inventor [invention (steam × airship or metal man / baroque stylings) × (pseudo) Victorian setting] + progressive or reactionary politics × adventure plot = STEAMPUNK’.

I had always liked engraved illustration, and had accumulated many of the books produced by Dover Publications, Pepin Press and others that for a long time were the sole preserve of antique imagery and type designs outside the original publications. The books I have worked on since 2008 have given me an opportunity to explore nineteenth-century print design in some detail. Studying the scanned print catalogues and specimen books at the Internet Archive (archive.org), it is possible to discover the names of those peculiar typefaces, and see how elaborate page designs were pieced together by typesetters from many tiny decorative elements. The distilling of motifs and decor into a limited range of ingredients has made steampunk visuals easy to apply anywhere, from restyling by fans of favourite characters from film, television and comics (Steampunk Iron Man is one of the better examples) to iPhone cases. With increased visibility comes the inevitable reaction. Some SF writers (a minority) have voiced their concern that steampunk’s success is at the least frivolous, at the worst dangerously reactionary. This underestimates both the audience and the nature of the time that so fascinates their imaginations. The nineteenth century was a class-ridden era of imperialism and global exploitation that also saw the abolition of slavery and child labour, the birth of the suffrage movement and the foundations of feminism. It was the century of Das Kapital and the Communist Manifesto, the Paris Commune of 1871, and a great deal of anarchist philosophising. The imprisonment of Oscar Wilde coincided with the first moves towards a visible struggle for gay rights.

Steampunk writers have not been slow to acknowledge these developments or explore their possibilities via alternate histories. In the w2012 anthology Steampunk III: Steampunk Revolution, editor Ann VanderMeer writes: ‘At the Steampunk Worlds Fair in 2011, Emma Goldman (aka Miriam Rosenberg Roček) organised a mock late-1800s Worker’s Union Labor rally to illustrate to all what it was really like back in those days. Can you think of a better way to teach about a moment in history, to explain to a modern audience how things were then? She used creative ways to challenge the status quo and to think about change – and she used steampunk cosplay to do this.’

As for the design, Adolf Loos is no doubt spinning like a lathe at the thought of a resurgence of excessive ornamentation, but steampunk cares little for the approval of design’s gatekeepers. Randy Nakamura’s dismissal of the subculture’s enthusiasts as naive hobbyists (Design Observer, 7 July 2008) roused considerable anger but did nothing to halt the writing of the novels that still provide the foundation of the scene (and which Nakamura ignored), or the growth of steampunk conventions, more than twenty of which were held in the US alone in 2012.

Bruce Sterling, writing in The Steampunk Bible (2011), believes this persistent popularity has a wider message for us all: ‘Steampunk’s key lessons are not about the past. They are about the instability and obsolescence of our own times. […] We are a technological society. When we trifle, in our sly, Gothic, grave-robbing fashion, with archaic and eclipsed technologies, we are secretly preparing for the death of our own tech.’

This might be true if grave-robbing were all that was happening but there is a level of creativity and invention at the heart of the movement which is unusual in a time of such widespread and passive consumerism. As Ann VanderMeer notes, some are trying to learn from the past rather than merely plunder it. Or celebrating a future that never happened, one in which the Industrial Revolution did not run out of steam, and airships became a successful mode of mass transport.

Rifling the nineteenth century is not especially new, as the fashions of Swinging London (and the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper album) demonstrate. What is new is the unprecedented fascination with outmoded technology. Victorians didn’t fetishise cogs, dirigibles and steam engines, they fetishised the natural world that was being displaced or destroyed by the Industrial Revolution and the growth of cities. Even the abstract print decoration of the period, which in nineteenth-century printers’ manuals assumes an endless variety of ahistorical forms, crawls over the page like convolvulus, breeding borders, filling corners and sprouting flourishes from decorative capitals. A century of disapproval towards this kind of florid excess has collapsed at a time when all culture is being pushed from the physical world into inexpressive, featureless gadgets. Is it really so surprising that twenty-year-olds are curious about an over-decorated, physical era of conspicuous mechanics and heavy industry? Interest in antiquated graphic styles is now sufficient to prompt recent book-length studies such as Vintage Type and Graphics (2011) and Scripts: Elegant Lettering from Design’s Golden Age (2012, reviewed in Eye 80), both by Steven Heller and Louise Fili.

The question now is whether steampunk will continue to evolve or harden into a Bakelite block of pseudo-Victorian mannerism. Adventure films such as Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (2009) and Paul W. S. Anderson’s The Three Musketeers (2011) have spiced their remakes with steampunk visuals. The latter gave a pre-industrial story anachronistic airship battles and a title sequence by Momoco (see ‘Credits where due’ in Eye 80) that was a mass of interlocking and floriated metalwork. Genre cross-pollination is already occurring away from the novels, as in Stephen Fung’s 2012 martial arts film Tai Chi Zero, which describes itself as ‘a steampunk kung-fu throwdown’.

Whether this trend will continue, and where it will lead, remains to be seen. Maybe we can look forward to the emergence of Deco-punk or Moderne-punk. William Gibson’s short story ‘The Gernsback Continuum’ has its protagonist glimpsing scenes from an alternate 1980s in which the finned and streamlined utopias of early science fiction are a viable reality. But this presupposes that different aesthetics are equally attractive and interchangeable, which is not the case. Steampunk’s attraction remains its resolutely pre-Modern nature, however postmodern its mixing and repurposing may be.

Design critics have been looking for a defining aesthetic now that we are well into the twenty-first century. I propose that for the moment – for better or worse – steampunk in all its disreputable retro glory is it. Nothing else is proving this popular, this recognisable and this flexible, capable of being applied to fiction of any genre, films, computer gear, jewellery, fashion (Prada’s Fall / Winter 2012 menswear collection was quasi-Victorian), motor bikes, wedding ceremonies, music (there are steampunk bands) – even the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games. Those who can’t stomach the frivolity may take solace that Modernism arrived while the Victorians were looking back at the medieval world. Whatever is coming next may be lying just below the horizon, waiting to emerge from the vapour ahead of us.

Image from The Three Musketeers, 2011. Production designer: Paul D. Austerberry. Supervising art director: Nigel Churcher. Director: Paul W. S. Anderson

First published in Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

John Coulthart, illustrator, designer, writer, Manchester

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 86 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.