Winter 2007

The 'L' Word

Not all designers are liberals. But you’d never know it from design conferences. Or the pages of Eye…

That all graphic designers, like all creative people, are somehow politically progressive, even if the majority are not Marxist firebrands, is a fallacy perpetuated by liberal and left-wing designers. History actually tells a more complex story – just look at F. T. Marinetti, Paolo Garretto, Fortunato Depero or Ludwig Hohlwein and their respective links to Fascism, assuming, of course, we can agree that Fascism is not progressive. Nonetheless, each believed that their art and design served a social revolution, and in that sense it was progressing the cause.

Yet if you read design magazines and blogs, liberal views dominate, especially in the United States. One would have been hard pressed to know for certain that any conservatives or right-wingers were in attendance at ‘Next’, the AIGA National Design Conference in Denver, October 2007 (see p.83). Many main stage speakers liberally railed against President George W. Bush and the Iraq war (which, although unpopular in the US, is rarely actively opposed except from the left). When, half way into the conference, the master of ceremonies, Kurt Andersen, announced that Al Gore had just been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize there was such enthusiastic applause one might think all attendees were in total accord.

Red and blue and shades of grey

Not so. There are various shades of political grey within the design world, particularly in the US, where for the majority of the Bush years the electorate’s loyalties have been almost equally split. Nonetheless right-leaning designers have largely been under-represented – or drowned out entirely - in the political design discourse.

Recent books about design and politics in the US and UK (Design of Dissent by Milton Glaser and Mirko Ilic; Conscientious Objectives: Designing for an Ethical Message by John Cranmer and Yolanda Zappaterra; and Street Art and the War on Terror: How the World’s Best Graffiti Artists Said No to the Iraq War, edited by Eleanor Matheison) present unapologetic liberal / left perspectives. The design magazines, Print, Communication Arts, Eye, etc., have also featured more stories about oppositional graphics and guerilla advertising than on pro-conservative media.

Meanwhile, mainstream design associations in the US and also in Europe have not been reticent about voicing oppositional views: in 2003 and 2004, respectively, the New York AIGA chapter sponsored two evenings – talks and panel discussions – devoted to political protest called ‘Hell No!’ and ‘Hell Yes!’ (the latter so named because it was an election year in which it was assumed Bush would be voted out of office). These addressed preparations for, and the ultimate declaration of war against Iraq. In 2005 the travelling exhibition ‘Graphic Imperative: Posters for Peace, Social Justice, and the Environment 1965-2005’, subsequently supported by AIGA and other design groups, began appearing on college campuses and at design events throughout the US.

In 2006 the New York Art Director’s Club hosted ‘Designism’, featuring Milton Glaser, Jessica Helfand, George Lois, James Victore, Brian Collins and Kurt Andersen, which volubly promoted a liberal agenda of social responsibility; a follow-up event in December 2007 attracted a large supportive crowd. (Full disclosure: I was involved in all these events.)

Since Bush assumed office, flash points – from ballot fraud to abrogating civil rights to starting wars against ‘terror’ – have been addressed with various degrees of vigour and passion at conferences and symposia. Conversely, there have been no exhibitions, conferences, seminars or ‘small talks’ advocating conservative policies sponsored by design organisations. Conservative designers have not managed to garner support for political events of their own, leaving them feeling frustrated.

After one session where President Bush was lambasted at the Denver AIGA conference, I talked to a few attendees who readily complained that injecting partisan political rhetoric into what they believed was supposed to be a ‘neutral’ organisation challenged their faith in AIGA’s ability to represent them. Although they wanted to remain members of the sole national professional design organisation in the United States, they resented having to put up with what they construed as negative, at times offensive, ‘propaganda’, as though their opinions were irrelevant. Asked whether they would consider starting counter-initiatives, they lamented that their views would never get taken seriously, so why bother.

Most of the anger about mixing design and politics therefore surfaces on blogs and chatrooms, which provide a ‘safer’, more anonymous playing field for dissenters than conferences, where they may be made to feel uncomfortable. The Web allows unprecedented public access and the capacity to argue without filters. Liberal / left political posts on websites such as Design Observer and Speak Up trigger vociferous disdain. The majority of conservative complaints, like this one submitted to Design Observer in response to William Drenttel’s 31 May 2007 post ‘Gore for President’, argue that this is an inappropriate place for political posturing: ‘I’m not the least bit pleased to see a place that is usually home to great critical design writing turned into an ad for Al Gore.’ This response raised sincere concerns over whether this blog should take partisan stands.

Objections run the gamut from mildly civil to harshly personal; others express disdain for the ‘knee-jerk’ nature of liberal / left politics. While politics has been part of the design discourse for decades, only recently has the argument on both sides been so vocal. Overall, those who oppose politicised design discourse seem to fall into two camps. One faction objects to being ambushed by political messages and also believes design writers have no credibility in the political arena (which is not unlike how some people view movie stars and other celebrities who stand for causes). ‘Designer writers could do the political processes of the world a great favor by taking… their nonsensical idealism elsewhere and leaving the heavy thinking up to people who actually have a clue,’ wrote a reader of Design Observer. The other faction simply resents challenges to their own passionate views.

Injecting politics, of whatever leaning, into the design discourse is obviously a recipe for antagonism. But why must this be? Designers are no more divorced from politics than any other aware citizens, so to restrict, as some have proposed, discussion on design blogs or at conferences to designer-specific themes, such as typography, would misrepresent the design discourse. Even type has political ramifications in how it is used to convey messages.

Selective outrage

Those uncomfortable with (or unwilling to engage in) political discourse can opt out of the Web discussions, although it is increasingly more difficult, since so much discourse is taking place on the Web. The temptation to rebuke unacceptable views is just too great for some, particularly when personal values are under attack. A 2004 Speak Up discussion of anti-Bush policy buttons designed by Milton Glaser prompted this response: ‘Am I the only one who sees this hypocrisy? Where are the posters and buttons and AIGA conventions and designers voicing outrage against abortion?’ Anti-abortion graphics do rarely make it into design shows, and the accusation that there is a liberal / left conspiracy to deny access of this view in this kind of competitive forum may have some validity. What’s more, there are other concerns that transcend Left versus Right. When in 2002 ‘Don’t say you didn’t know’, an exhibition of pro-Palestinian posters, was hung at the AIGA Voice conference in Washington DC, outrage against images that many interpreted as supporting suicide bombing triggered a fierce debate among otherwise socially simpatico liberals.

Asked about the role of political discourse in the classroom, Paul Rand asserted that design education was not a good venue for politics: it should not be ignored, but rather kept at bay. Political content, he suggested, was so charged it could distract from teaching formal issues.

There is an argument, put by British designer Quentin Newark in a letter to Eye (no. 48 vol. 12) about criticism of the D&AD, that all design journalism is rooted in social or political bias: ‘Isn’t all judgement of design about employing values, and aren’t these always informed by hidden factors… I find much of the journalism in Eye strongly coloured by barely disguised “factors” – a loathing of commerce; fetishisation of the idea of the avant-garde; fantasies about radical politics. Do these “factors” behind a good many of the pieces in Eye make it inadequate?’

I became engaged in design largely because design was so integral to the political process. This is why I was encouraged by this blog comment: ‘Reading Design Observer and saying “hold the polemic” is sort of like going to Hooters [a us restaurant chain known for its buxom waitresses] for the food. Thank goodness the art of Pamphleteering lives on. Designers, where do you draw the line?’

Yes, the lines have changed because new technologies – blogs, digital video, podcasts and a wealth of community sites – have made soapboxes out of our desktops. Designers increasingly take advantage of these opportunities – in fact, are drawn – to express political opinion. As the traffic grows, doubtless more dissenters will challenge liberal / left assumptions, and that’s a liberal thing.

Steven Heller, design writer, New York

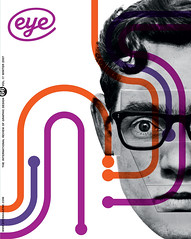

First published in Eye no. 66 vol. 17 2007

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.