Winter 2026

Voice at the table

various designers

anonymous designers

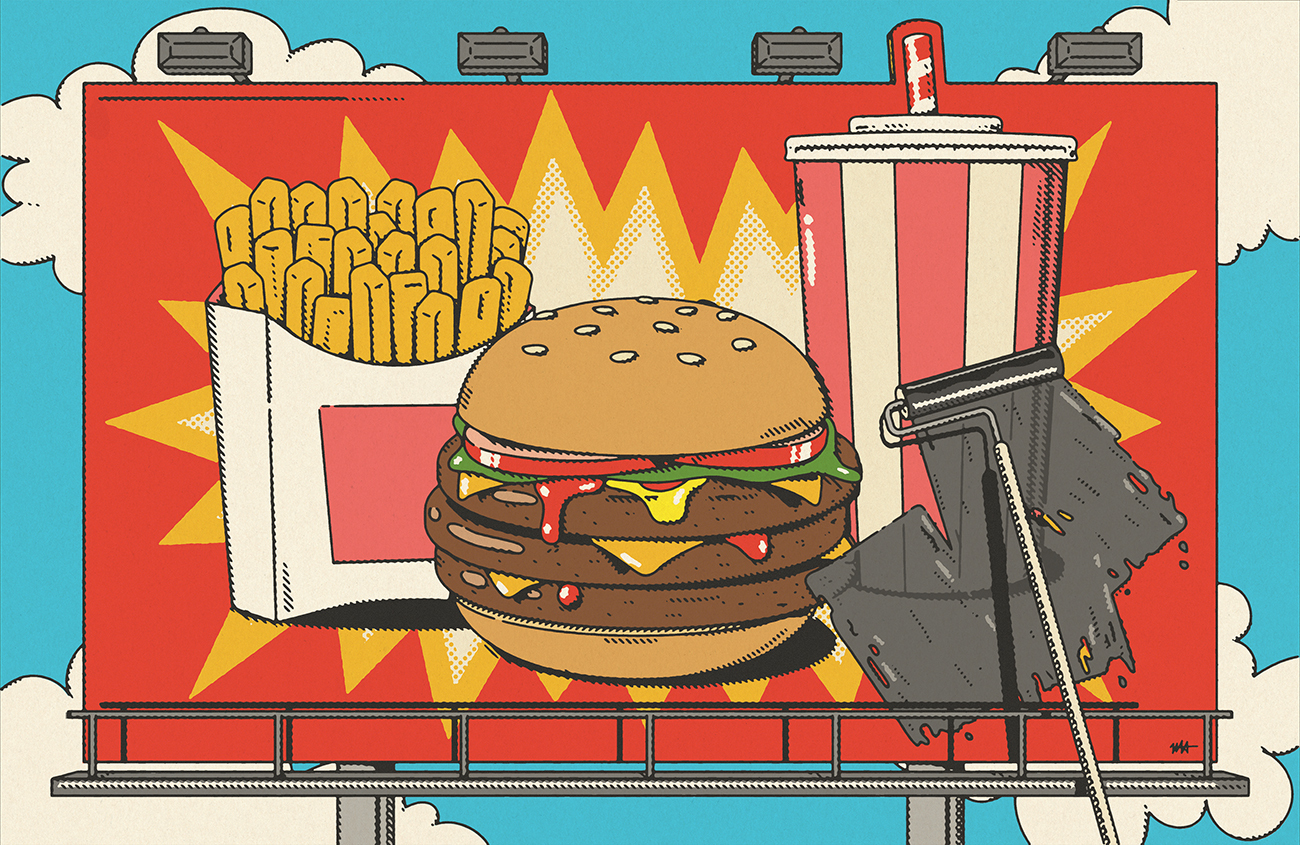

Michael Haddad

Brand madness

Critical path

Food design

Agenda

Will we one day view junk food ads the way we look back on tobacco advertising? Nigel Ball challenges designers to query the relationship between branding and UPF (ultra-processed food)

Long before we use our senses of taste or smell, the decision about what we put in our mouths is often influenced by another sense: sight. Whether through packaging on supermarket shelves, advertising, restaurant signs or brand label loyalty, when it comes to food, the visual choices we make affect not just our dietary habits, but also our health. Considering the various problems related to the over-consumption of ultra-processed food (UPF), what does this mean to a design industry that is intrinsically part of the system of food production and promotion? These days, few people look back proudly on the design industry’s involvement in cigarette advertising.

In his popular 2023 book Ultra-Processed People: Why Do We All Eat Stuff That Isn’t Food … and Why Can’t We Stop? (Cornerstone Press), doctor and broadcaster Chris van Tulleken explores the topic of ultra-processed food. Yet, given the number of times that packaging, advertising and branding are mentioned, you could be forgiven for thinking it a book about graphic design. To tackle the subject, Van Tulleken decided to replace 80 per cent of his diet with UPF products, and this resulted in numerous observations about the ways packaging graphics influence food choices.

For example, Van Tulleken discovered that his three-year-old daughter would ask to eat the breakfast cereal with a monkey on its box, rather than her usual porridge. And while on a camping trip, he recalls that a psychology professor friend assumed that a muesli brand was a ‘healthy option’ because the box depicted a snow-topped mountain. This led him to question the scale of the packaging imagery in relation to its nutritional info, such as salt and sugar content.

According to the book’s introduction, ‘[UPF] damages the human body and increases rates of cancer, metabolic disease and mental illness … it damages human societies by displacing food cultures and driving inequality, poverty and early death.’ Van Tulleken avoids blaming people who become addicted to UPF products, writing: ‘It’s not you, it’s the food.’ By extension, one could say: ‘It’s not you, it’s the graphics.’

Outside the home, advertising for junk food seems omnipresent. The term ‘food swamp’ relates to an urban area that is swamped by fast-food outlets with their bright window displays and brand signage. These are often the neighbourhoods in which teenagers hang out, where their dietary choices are influenced by the attraction of low-cost, ultra-processed food via attention-grabbing graphics. Walk around any town centre today and you will see adverts for burgers and fries adorning disused telephone kiosks, shouting about the latest price deal. This repurposing of outmoded communications infrastructure often spreads outwards from food swamp areas, working as a tool to draw people towards an outlet like the Pied Piper of visual communication.

BiteBack, the youth activist movement that aims to call out the manipulation of junk food giants, describes this as ‘a food system that’s been set up to fool us all.’ Founded in 2021, this imaginatively titled group has set its sights on advertising and marketing, believing these to be central problems in the targeting of young people by fast-food giants who ‘flood our world with their products, then manipulate us using cute, colourful, clever marketing. They deceive us with packaging, and pump millions into making sure their junk-filled products are always in the spotlight … It’s the cultural wallpaper.’

Mission creep

BiteBack asks us to imagine and demand ‘a world where global food companies are held to higher standards. Where government policymakers protect us by regulating “Big Food”. And where schools are a safe space, free from the corrupting influence of junk food.’ Over the past four years, the organisation has lobbied the UK Government to extend free school meals available during lockdown, alongside many other initiatives to protect child health. In 2024, it called for government regulations to prevent the increase of fast-food outlets opening up near schools after research by the University of Cambridge concluded these had increased by 59 per cent in ten years. Such UPF ‘mission creep’ threatens to turn centres of learning into food swamps.

BiteBack then called for further restrictions on out of home (OOH) advertising for junk food. In April 2025, the organisation launched a #CommercialBreak campaign and bought up ad spaces in London to display the message: ‘Young Activists Bought This Ad Space So Junk Food Giants Couldn’t.’

Using the advertising tactics of the fast-food giants – and demonstrating a savvy understanding of the persuasiveness of the industry – the campaign won a Sheila McKechnie Award for Best Consumer Campaign. Given that BiteBack discovered in 2024 that food and drink companies spent over £400 million pounds on street advertising, it will come as no surprise that the campaign has been rejected by two big media companies – a sure sign that BiteBack has rattled some nerves in the ad industry.

A recent study by University College London and UCL Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust into ultra-processed food and weight, published by Nature Medicine, made strong recommendations that all UPF products need warning labels. The report stated: ‘Marketing and advertising heavily influence eating behaviour … Although no products on the UPF diet included “reduced calorie” labelling, many carried nutrition or health claims. This may have influenced eating behaviour and perceptions of appropriate portion sizing, eating the suggested UPF portion sizes compared with eating ad libitum on the MPF [Minimally Processed Food] diet.’

With this, and the agit-prop challenge of BiteBack’s #CommercialBreak campaign, graphic design appears to be both part of the problem and part of the solution when it comes to our health. This is nothing new, and many designers will reflect negatively on past ‘creative’ – and award-winning – campaigns that at best promoted dubious causes, and at worst sold us life-threatening products. Some studios now have ethical policies that eschew unacceptable clients.

Traffic-light data tables

It is worth considering that in working with clients, designers have a ‘voice at the table’, and therefore the ability to affect change. Food labelling guidelines, including the controversial and misleading ‘traffic light’ colour-coding and nutritional data tables used in the United Kingdom, could be a good place to start. Van Tulleken has stated that they need to be redesigned, viewing them as a blanket tool with too little detail, overshadowed by the visual dominance of other images on packaging. Nor is it just a UK issue. The UCL report noted that the findings are relevant to many countries, given ‘… the similarities between UK and most dietary guidelines worldwide that do not consider UPF.’

Van Tulleken’s research and BiteBack’s campaigning points to a health crisis already rampaging through our kitchens, stores and high-street food swamps – one that the design and branding industry needs to tackle.

Nigel Ball, designer, educator, writer, Ipswich

Illustration by Michael Haddad / Heart.

First published in Eye no. 109 vol. 28, 2025

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.