Autumn 2023

Going off brand

What is Post-Branding? How to Counter Fundamentalist Marketplace Semiotics

Jason Grant and Oliver Vodeb. Designed by Inkahoots and Oliver Vodeb. Set Margins, £20

Jason Grant and Oliver Vodeb’s uncompromising handbook of theory and action ends slyly with a ‘Brandspeak’ quiz, a series of eight mission statements the authors found on the websites of companies offering branding services. These putative USPs make for depressingly uniform reading: ‘brand consultancy’, ‘global brand strategy’, ‘transformative brands’, ‘brand building tools’, ‘brands that can’t be ignored’, ‘brands that seek to be brave and challenge convention’. The designers’ names have been redacted from the quotations. Revealed over the page, some sources are entirely predictable (Landor, Interbrand, Wolff Olins), others (MetaDesign, DixonBaxi) a sign of how pervasive this way of framing and promoting graphic communication has become. Searching the statements, I found cases where they had been plagiarised on other designers’ websites.

Grant and Vodeb see branding as utterly corrosive. They seek to reveal this harmful practice ‘as a symptom and catalyst of scorched earth capitalism’ and an ‘insidious neoliberal project of self-sabotage’. They want designers to ‘pull the plug’ on branding and terminate the industry and they call on universities to strip branding out of the curriculum. They argue that under the guise of being a neutral process branding has diluted democracy by colonising the public sphere and distorting everything it touches, from ordinary social interactions to the relationship between governments and citizens. Branding has become our 21st-century culture: ‘Brands don’t just want our loyalty, they want our love, they want our-selves.’

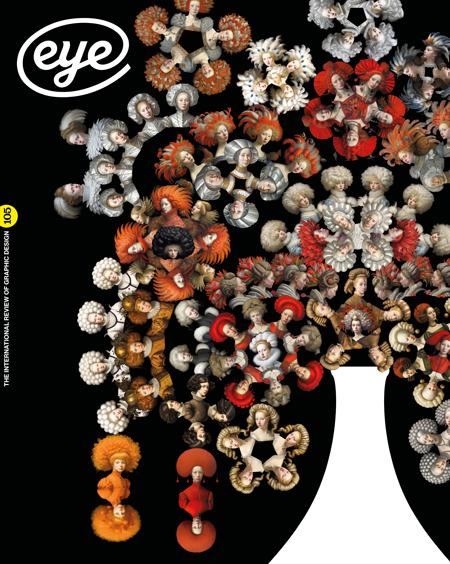

Cover design by Inkahoots and Oliver Vodeb.

Top. Spread from What is Post-Branding? showing pages from the organisational handbook of the National Socialist Party (1936) opposite pages from an IBM graphic design guide by Paul Rand (1981).

The book’s resolution and stridency are both a strength and a handicap, depending on the reader’s starting point. The first part takes the form of twenty one-page statements outlining their critique. The style is punchy and manifesto-like, though for readers who aren’t already sympathetic to their case it takes a lot for granted. Both authors are deeply political. Grant is a radical designer at the Inkahoots studio based in Brisbane, while Vodeb, now teaching in Melbourne, co-founded the Memefest international network in Slovenia. In a nicely sardonic touch, their authors’ photographs show them in sober suits and ties like a pair of wannabe top-flight branding consultants.

For designers who don’t share their leftist political position, it may be harder to grasp what the fuss is about. As those website statements make clear, many design-worlders gulped down the Kool-Aid a long time ago. The industry’s efforts were instrumental in helping branding to become the master narrative in the 1990s. By 2000, the V&A, no less, was mounting a massive survey show about branding, titled ‘Brand.New’. ‘The idea of the brand is central to contemporary society,’ the catalogue noted. ‘Businesses, personalities, political parties and even nations “re-brand” themselves in order to influence public opinion.’ Eye’s ‘Brand madness’ special issue (no. 53) – with a lacerating takedown of Wally Olins’ book On Brand (a ‘pile of cold-hearted cynicism’) – was published nearly twenty years ago.

It’s commonplace inside social media’s hall of mirrors for people to imagine themselves to be a brand. The glib assertion that everything and everyone can be reduced to a brand shows how relentless and controlling the ideology of the marketplace has become. There have been absurd attempts to argue that even Paleolithic cave paintings represent a form of branding. As Grant notes, ‘retrofitting branding … as some kind of ahistorical process just falsely paints it as inevitable.’ And when a phenomenon is portrayed as inevitable – a natural tendency – it squeezes out other possibilities. The book’s second section is a deftly researched visual essay with many revealing pairings of images. One spread shows posters produced by Amnesty International before and after Wolff Olins’ global rebrand in 2008. The later posters are consistent and clear, but they are also corporate and dull with far too much yellow (the new brand colour). They lack vitality and feel less humane – a startling shortcoming when caring about human welfare was the aim.

Grant and Vodeb hope there can still be other worlds of communication to express our interdependencies, needs and desires. This ‘post-branding’ will depend on three creative methods: transparency and open-source principles, participatory design, and diversity and collaboration. The examples of projects that follow are notably looser and more improvised in feel with greater evidence of the individual hand. This visually inventive pocket book, pleasingly light to handle, is a vital manual of resistance to the manipulative fundamentalism of the contemporary marketplace. Every graphic designer with a conscience should read it, weigh up its findings, heed its call to rethink, and find ways to apply its life-affirming insights.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, professor of design and visual culture, University of Reading

‘What is Post-Branding’ published by Set Margins

First published in Eye no. 105 vol. 27, 2023

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.