Summer 2022

Unfinished narratives

Briar Levit

Angel De Cora

Betti Broadwater Haft

Louise E. Jefferson

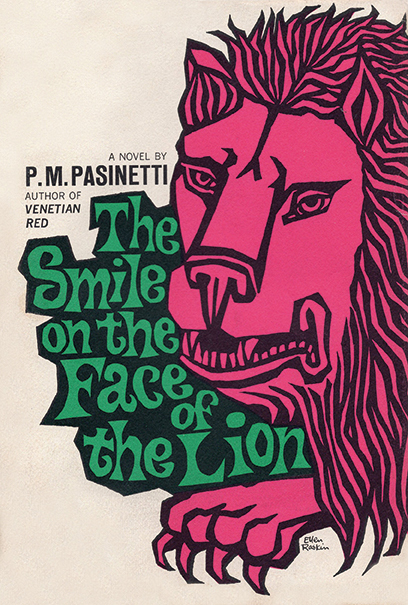

Ellen Raskin

Bea Feitler

Norma Kitson

Söre Popitz

Marget Larsen

Design history

Reviews

Typography

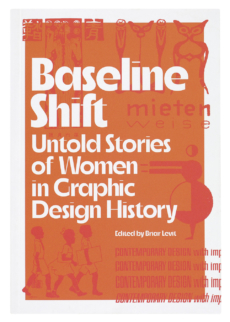

Baseline Shift: Untold Stories of Women in Graphic Design History

Edited and designed by Briar Levit. Princeton Architectural Press, £25, $27.50.

In recent years, there has been a surge in the number of books and projects that challenge what has been universally accepted and understood as the graphic design canon. The creation of publicly accessible collections of graphic design ephemera, such as the ‘Letterform Archive’ (featured in Eye 100) or the crowd-sourced ‘People’s Graphic Design Archive’, help recognise previously ignored narratives and underrepresented voices. The latter was co-founded by Briar Levit, designer, educator and the filmmaker behind the documentary Graphic Means (see Eye 95).

Levit’s book Baseline Shift aims to shine a light on women who in various ways have shaped the history of visual communication. Fifteen essays seek to examine ‘the variety of alternative approaches and activities that are often part of women designers’ professional lives.’ Organised into four sections, ‘Publishing’, ‘Activism and Patriotism’, ‘Press and Production’, and ‘Commercial’, the collection is by no means comprehensive, but it provides a window into previously unseen lives and practices of women designers, typesetters, illustrators, printers and activists. Moreover, as the book exists through the collective effort of different writers, we are reminded that history is not authored by a single person, but many.

Taken together, these stories also question what is often narrowly classified as ‘graphic design’, defining it as a complex, social and cultural practice instead of merely an economic one. As a result, they broaden the scope of history and embrace its ‘messiness’. This framing, outlined by Levit in the book’s introduction, stems from the writings of design historian Martha Scotford (see ‘Googling the design canon’ in Eye 68), who identifies socio-economic contexts and systemic inequalities as key factors for overlooking women’s contributions to design.

The book’s opening essay, ‘Her Greatest Work Lay in Decorative Design’, by scholar Linda M. Waggoner, unveils the life and career of Angel De Cora, Ho-Chunk Indigenous artist and designer. Waggoner, who in 2008 wrote De Cora’s biography Fire Light, focuses on her continuous balancing act of Native American heritage and Western upbringing, as De Cora fought for recognition of authenticity in the graphic visual languages she designed.

In the final essay, educator Anne Galperin presents the career of Betti Broadwater Haft, whose career spanned 50 years of ‘making a living’, as she describes it. As a skilled graphic and type designer, Haft navigated through different, often difficult circumstances, including predatory and sexist work environments, motherhood, or becoming primary breadwinner, as she continued to pursue her passion for letters.

What lies in between is a cross-section of stories about British colonial printers (by Sarah McCoy), collective authorship and creative process (by Aggie Toppins), print in Japan (by Ian Lynam), Suffragist activism (by Meredith James) and that of The Federal Art Project (by Katie Krcmarik). In other pieces we celebrate the lives of Louise E. Jefferson, Ellen Raskin, Bea Feitler, Norma Kitson, Söre Popitz, and Marget Larsen (see Eye 102), who each present a rich contribution to the design canon.

Ellen Raskin‘s cover for The Smile on the Face of the Lion, 1965. Raskin used woodcut lettering to create new flared type forms. Top. Patricia Saunders using the enlargement camera at Monotype’s Type Drawing Office, 1955.

Lastly, ‘The Invisible Women of Monotype’s Type Drawing Office’, by Alice Savoie and Fiona Ross, and ‘Feminist Historiography of Print Culture and Collective Organizing’ by Maryam Fanni, Matilda Flodmark and Sara Kaaman, illuminate the collective nature of designerly activity and ultimately critique the notion of the ‘solo designer’. After all, graphic design does not happen in a vacuum, but is reliant on inter- and cross-disciplinary collaborations, varied specialisms, and technologies, while also being affected by the surrounding political, economic and social contexts.

For those seeking expanded understanding, there is a comprehensive list of references, sources, and indexed terminology, as well as the contributors’ biographies in the final section of the publication. The afterword, by Scotford, closes the book with a reflection on research as a gratifying but time-demanding activity.

Baseline Shift provides a more empathetic and intersectional approach to chronicling design in the form of a handy and accessible resource for anyone interested in expanding their understanding. The book casts its net wide, bringing diversity into more familiar white, male and western-centric perspectives, suggesting that our inherited canon does not account for all the meaningful activity of the past.

Baseline Shift evidences the fact that women historically have not been absent from graphic design, they simply were not deemed as noteworthy by their contemporaries. Finally, the book begs the question of not only who is included in the conversation today, but more importantly, who is missing. For me, Baseline Shift instilled both a sense of dissatisfaction with conventional narratives, and impatience for what lies ahead, as the scope for critical research that was not included (as it is yet to be completed) feels as monumental as it is inevitable.

Throughout this book, Levit challenges archaic hierarchies that contribute to the erasure of history in the glorification of singular artefacts and / or their individual creators. In doing so, she carves out a space for a more nuanced and sensitive approach to archiving for the next generation of designers, writers and researchers. Returning to Scotford’s words in her 1994 essay ‘Messy History vs. Neat History,’ Baseline Shift echoes that call for continuous and comprehensive historical and cultural study of graphic design. ‘It is complex, it is undefined, it is messy, but the rewards will be great.’

Cover of Baseline Shift, designed by Briar Levit. Top. Patricia Saunders using the enlargement camera at Monotype’s Type Drawing Office, 1955.

Gabriela Matuszyk designer, writer, educator,

London

First published in Eye no. 103 vol. 26, 2022

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.