Autumn 2021

Rebalancing the design canon

Elizabeth Resnick looks at the practitioners and educators intent on revising our understanding of women’s roles in design history

ShandyGaff ‘healthy food’ hot spot in San Francisco with supergraphics by Marget Larsen, 1971.

In 1991, in the AIGA Journal of Graphic Design, US designer, design educator and historian Martha Scotford published her seminal article ‘Is There a Canon of Graphic Design?’. She chose five books that were considered the best historical surveys at that time and applied a statistical analysis to question their inclusion criteria. Later, in Eye 68, she wrote: ‘When I researched my 1991 article by counting images, I claimed that the authors of the five books involved had unintentionally created a canon.’

But is there a genuine canon of graphic design history?

‘Graphic

design history is, generally speaking, a history of professional

practice,’ wrote US designer and design educator Aggie Toppins in

an article for AIGA

Eye on Design.

‘In

text books, at conferences, and for college courses, design

historians and educators explain the development of the industry

through the example of pivotal figures, canonical works, and dominant

styles.’

‘Errata: A feminist revision to Portuguese graphic design history’, Gabinete Gráfico, Museu da Cidade, Porto, from 27 August to 23 October 2021. Exhibition design ID-AE studio. Installation photo: Alexandre Delmar.

The

first historians to show an interest in graphic design were

professionals seeking greater recognition.

Toppins writes that this ‘movement … saw a need to create a history to elevate graphic design above an amateur’s knowledge, decouple the industry from trade disciplines, and position the field as an equally important cultural player alongside architecture, fashion design, and the fine arts.’

Ruth

Sykes, a UK designer and design educator, believes this to be an

unfortunate consequence of an otherwise positive step. ‘Graphic

design history has largely foregrounded the achievements of male

graphic designers,’ she says, ‘leaving the contribution of female

graphic designers underexamined.’ Keenly aware of this oversight,

Sykes says: ‘If graphic design history were revised to include more

of the accomplishments of female graphic designers, it would be one

part of the process of achieving equal industry status for female

graphic designers.’

Italian

designer and design educator Silvia Sfligiotti offers a different

perspective. ‘Expanding the canon by adding more “masterpieces”

designed by women, or names of female “masters” would not solve

the problem of a lack of critical attitude,’ she argues. ‘Talking

about how a canon is created is more interesting.’

‘We

have a vested interest in dismantling the canon,’ adds US designer

and design educator Katie Krcmarik. The people with the power wrote

the history books and unsurprisingly wrote about people like

themselves.’

Since

1990, there has been a disproportionate influx of female students

entering design courses. ‘Women have made up a good amount of the

student body in graphic design programs, but their professional work

seems to be underrepresented in popular canons,’ says Louise

Paradis, a Canadian designer and design educator. ‘What has

happened to all these female designers?’ A feasible riposte is that

female graphic designers often combine teaching with their practice,

resulting in a substantial increase in both part-time and full time

female faculty members in colleges and universities over the past two

decades.

‘When

I started working as a graphic designer and talking to other female

designers,’ recalls Tereza Bettinardi, a Brazilian designer and

design educator, ‘I realised how few female references we had

during our education and early professional lives. I believe the

canon of graphic design history is still very male and white. But I

hope this will change in the future.’

US

designer and design educator Tasheka Arceneaux-Sutton says: ‘Design

history plays a huge role in my research, and lately I have focused

on Black women graphic designers.’

Expanding

a ‘canon’ fully to embrace the accomplishments of female graphic

designers is being addressed by an international cohort of

professional female graphic designers and design educators. To tackle

this biased imbalance, they have shifted their professional practice

towards researching, writing and curating exhibitions on

marginalised, overlooked and underappreciated female designers.

Collectively, they aim to question and challenge the widely accepted

pantheon of established male figures and, by doing so, reinvigorate

the canon of graphic design.

Seeking

role models

Hall

of Femmes is a project founded in 2009 by Swedish designers and

design educators Samira Bouabana and Angela Tillman Sperandio. It

includes lectures, exhibitions, interviews, podcasts and the Hall of

Femmes book series (see

Eye

94).

Each book in this series features a designer and her work via

in-depth interviews and previously unpublished images. ‘The project

started as a personal desire to find female role models in graphic

design – a field where women’s contributions to developing the

profession had not been documented or had enough recognition.’ A

book on Rosmarie Tissi, their tenth, is promised.

Australian

affirmation

#afFEMation:

Making Heroes of Women in Australian Graphic Design

is a website created by Australian designer and design educator Dr

Jane Connory (see

Eye

blog, July 2018).

Her PhD research focused on women’s visibility, diversity in design

and gender equity in Australian graphic design. She created

#afFEMation

(affemation.com)

– a network of women in Australian graphic design – to help young

designers develop their networks and find mentors to build their

careers. ‘When today’s design educators question the existing

canon and seek out or create resources to widen its scope, the

students benefit on so many levels,’ Connory says. ‘Graphic

design graduates coming out of universities and colleges across the

globe are mainly women, which is ironic considering the dominance of

men in senior roles out in the industry. Some of these actions can

include bringing together teams of people to write the biographies of

women graphic designers on Wikipedia.’

Defying

the dumpsters

US

designer and design educator Louise Sandhaus says: ‘On completing

my book, Earthquakes,

Mudslides, Fires and Riots: California & Graphic Design 1936–1986

(see

Eye

90),

it was clear that the history I’d spent considerably more than a

decade compiling was just a crumb of a crumb of California’s

graphic design history,’ she says. ‘I knew there was a wealth of

designers and projects I had overlooked because of my own biases.

Among the designers still in need of research were women, of which

California boasted a particular abundance, thanks to the freedom that

they may have enjoyed here. […] It took three years of research,

writing, photography and design to realise the book A

Colorful Life: Gere Kavanaugh, Designer

(see

Eye

99)

by Kat Catmur and myself. And Kavanaugh had an archive of her work.

Few archives specialise in graphic design, and so, with no place to

go, much of this history ends up in dumpsters.’

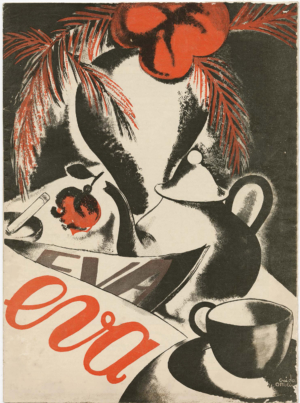

Images from ‘Errata’, Porto, 2021. ‘The process of

documenting and remembering is inherently misogynistic,’ write

curators Olinda Martins and Isabel Duarte in the exhibition

catalogue. Eva

magazine, 1933. Cover design: Guida Ottolini. Courtesy Biblioteca

Silva.

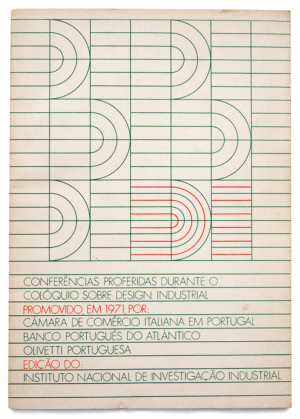

Alda Rosa’s catalogue cover for ‘Conferências Proferidas durante o Colóquio sobre Design Industrial’, 1971. Client: INII.

Portuguese

traces

Errata

is a relatively new project founded by Isabel Duarte with Olinda

Martins. The Errata

website (errata.design/en) states: ‘Errata is a para-academic

research project concentrating on the visibility of women in

Portuguese graphic design history. Disseminated through public

exhibitions and events, an ongoing series of podcasts and publishing,

the Errata project engages with criticism, education and research to

uncover the invisible stories of women designers in Portugal and

facilitate dialogues exploring methods of improving gender

representation in graphic design history.’ The first public

exhibition of the Errata research project took place in the Gabinete

Gráfico of Museu da Cidade in Porto from 27 August to 23 October

2021. ‘Through collecting, documenting and displaying the works of

Portuguese women graphic designers from throughout the twentieth

century, this exhibition will bring to the fore practitioners who

have been overlooked by canonical design history.’

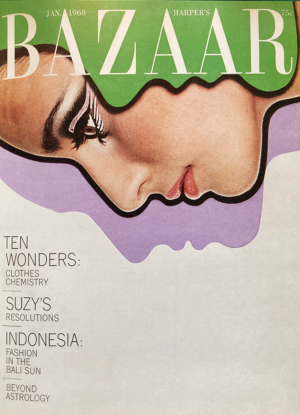

Harper’s Bazaar January 1968. Art direction: Ruth Ansel and Bea Feitler. Photograph by Bill Silano.

Shift

in perception

The

first book by Briar Levit, a US designer and design educator, is

Baseline

Shift: Untold Stories of Women in Graphic Design History

(2021). Its fifteen essays address subjects such as the book design

work of Ellen Raskin; Ho-Chunk indigenous artist and designer Angel

De Cora; Harlem Renaissance designer Louise E. Jefferson; South

African typesetter and anti-apartheid activist Norma Kitson; San

Francisco designer Marget Larsen; and Bea Feitler. ‘Graphic design

history has become the centre of my academic research after making

the documentary Graphic

Means: A History of Graphic Design Production’,

says Levit. (See

article in Eye

95.)

Truck with Marget Larsen’s Parisian Bakerie identity, 1960.

Changing

the frame

In

1994, US designer, design educator and historian Martha Scotford

wrote ‘Messy History vs. Neat History: Toward an Expanded View of

Women in Graphic Design’, published in the journal Visible

Language

(28:4). Scotford states: ‘For the contributions of women … to be

discovered and understood, their different experiences and roles

within the patriarchal and capitalist framework they share with men,

and their choices and experiences within a female framework, must be

acknowledged and explored. Neat history is conventional history: a

focus on the mainstream activities and work of individual, usually

male, designers. Messy history seeks to discover, study and include

the variety of alternative approaches and activities that are often

part of women designers’ professional lives.’

Elizabeth Resnick, design educator, curator, writer, Massachusetts, US

First published in Eye no. 102 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.