Spring 1992

In search of Barney Bubbles

He was a pioneer of British graphics, but he refused to sign his own work

To describe Whitton, on the outskirts of west London, as a suburb is to do it an injustice; Whitton is the epitome of English suburbia. A conservative backwater beneath the Heathrow Airport flight path, it is a place of half-timbered houses, respectable concern for what the neighbours think, and the preservation of the status quo.

It is from this unlikely background that Barney Bubbles came. Now, more than eight years after his suicide in 1983, he is rarely mentioned. Many people who knew his work did not know who designed it, because he almost never put his name to it, preferring to sign himself by his VAT number, any amount of joke names or nothing at all. With only the scantest appearance in the design manuals of his day, even the most assiduous design historian could have remained completely unaware of him.

Yet many of the British designers who made their names in the 1980s – among them Neville Brody and Malcolm Garrett – cite Bubble’s eclectic appropriation of twentieth-century art and suburban kitsch as a vital influence. It also looks as though Bubbles is at last beginning to find his way into the canon. Richard Hollis, author of a history of graphic design to be published by Thames and Hudson in 1993, will include material on Bubbles. Hollis describes him as ‘much the most interesting graphic designer’, saying: ‘He’s a key figure, he can be put on an international level. He had a direct line to creativity. Designers tend to manipulate imagery, not create it; Bubbles was like a real artist.’

On the record

Bubble’s favourite medium was the record sleeve. Trivial, ephemeral, and available to everyone, it suited his lack of preciousness about his work, while giving him almost total creative freedom. Remembered with awe by one generation of rock fans for his foldout album covers for Glastonbury Fayre and Hawkwind in the early 1970s, Bubbles is equally revered for his work for punk and new wave bands on the Stiff, Radar and F-Beat record labels. Superficially, his career might seem to span an unbridgeable gulf from the love-and-peace of the hippies to the hate-and-gob of punk. It is an indication of his intuitive grasp of what was right for the moment, and his seemingly instinctive ability to be in the right place at the right time, that his work is seminal to two such different eras.

But was Bubbles as good as his admirers insist? And if he was, why has his work been overlooked, or at least marginalised, for so long, unlike that of similar designers whose contributions in the 1970s and 1980s graphics are now widely acknowledged? Is the almost mythic reputation Bubbles retains among a few London-based designers at least in part a product of the sentiment that inevitably surrounds a talented, much loved person who takes his own life?

According to Hollis, Bubble’s decision to drop out of mainstream design and confine himself to the music industry is one reason why he was overlooked by the writers of his day. Another reason for his invisibility was that he went to great lengths to ensure it. Self-effacing to the point of adopting a new name (he was christened Colin Fulcher) and almost never signed his work, he purposefully denied himself recognition. It was just one manifestation of a puritanical streak in his character. ‘He had his own rules and regulations, his own religion,’ says his friend the photographer Brian Griffin. ‘He lived in incredible austerity. He asked me to stay the night once and I ended up sleeping on bare floorboards with bin liners over the top of me and newspapers underneath.’

After leaving school, Fulcher attended Twickenham College of Art in London. In 1965, he joined the then new and exciting Conran Design Group, where, at the age of 23, he was considered to be one of the brightest of the bright young things in the companies fledgling graphics department. Funny, idealistic and obsessively perfectionist – he produced immaculate artwork – he did not at that time display the instability and inability to cope with everyday life that later became evident.

By all accounts, he was, even then, immensely charismatic. It is a trait that is remarked upon by almost everyone who knew him; asked to comment on the designs, most people quickly turn to talking about Bubbles himself. As Pauline Williams, his assistant at Stiff Records, puts it: ‘There was an incredible power about him. People were drawn to him like a magnet. Even with people he disliked he could be the same.’

From Conran to counterculture

It was in 1967 that Bubbles metamorphosed from Colin Fulcher – designer at Conran, working on such projects at the Habitat catalogue and D&AD exhibitions – to Barney Bubbles, designer in residence to London’s rapidly emerging counterculture. He gained his new name from the liquid lightshows that he ran at venues such as the Roundhouse, using oil and food colouring to create wildly coloured, bubbling backdrops for the psychedelic music of the hippy underground.

Leaving Conran, Bubbles moved to 307 Portobello Road, a building belonging to a music company called Famepushers, known for the chutzpah with which it pulled off some notorious publicity stunts. In return for the space, he designed whatever they needed and increasingly worked on record sleeves and underground magazines such as Friends and Oz. ‘He was the loosest, most lateral thinker that I have ever come across,’ says Pearce Marchbank, then the art director of Friends. ‘He was always picking up little pieces of paper and shoving them in his pocket, saying: “I’ll use that later”.’

At Portobello Road, Bubbles started working with Hawkwind. Not only were the record sleeves that he created unlike anything that had been seen before – the cover of In Search of Space (1971) unfolds to reveal a stylised, cut-out hawk – but Bubbles also did everything from painting the drum kits to designing the stationery. Hawkwind’s Gothic sci-fi mythology was given a visual manifestation intricate enough to keep fans fascinated no matter how much acid they dropped. It was one of the first times that all of a band’s visual material had been treated as a whole, controlled by one person. To a designer such as Malcolm Garrett, then still at school, it was a lesson in what could be achieved: ‘The way Bubbles worked with Hawkwind influenced the way I wanted to work with the Buzzcocks, as part of a whole team, to present a unified picture.’

It was while working with Hawkwind that Bubbles began to explore twentieth-century art. With Hawkwind’s manager, Doug Smith, he would riffle through art books in search of Art Nouveau and Art Deco themes. Although this interest was in no sense unique – the revivalist vogue had been initiated by Push Pin in the late 1950s, and was a feature of British psychedelic poster art, as well as commercial projects of the early 1970s such as the Biba store identity – it shows that Bubbles had rejected the clean modernism of the 1960s for a more subjective and expressive approach to design. His subsequent development has marked parallels with that of Paula Scher, who joined CBS in 1972. In both cases, early revivalist influences led, in the late 1970s, to the reprisal and recycling of the work of the early Modernists.

Punk aesthetic

Always highly sensitive, Bubbles seems to have reacted badly to the erratic lifestyle and drug-taking that were the norm at Portobello Road. When things became too much for him he would disappear for days. On one occasion, his friends say, he took a job stacking supermarket shelves; on another he went to live on a pig farm. Increasingly as he grew older, he would retreat back to the security of his parents’ house in Whitton. Much of this time seems to have been spent reading art history books. Although suspicious of intellectualising, he absorbed the theories as well as the aesthetics, and was interested in everything from Constructivism to Situationists.

Returning to London in 1976 from a year’s retreat in Ireland, Bubbles landed in the middle of punk and immediately realised its significance. Jake Riviera, an old friend from the Portobello Road days, was setting up Stiff records and Bubbles became his full-time (freelance) designer. At Stiff anything went – the more outrageous the better. At one point, both Bubbles and Pauline Williams (then known as Caramel Crunch) were homeless and lived in Stiff offices. ‘I had the accounts department and Barney had the art department,’ Williams remembers.

Ignited by punk and fuelled by his reading, Bubbles’ designs took off. It provided the perfect medium for Riviera’s stunts and ruses for making people buy records. On one occasion, the company put a picture of the wrong band on the record sleeve in the hope that fans would also buy the corrected record a few weeks later. Bubbles’ unusual mixture of passion for his work, coupled with an inability to take it seriously, ensured he was at home.

‘Barney really embraced the punk philosophy,’ says Williams. ‘He was quite into nihilism and existentialism.’ Chris Morton, art director at Stiff, agrees: ‘He was suffused with the idea that this was a new start, and he was basing a lot of what he did on Russian art just after the revolution.’

Bubbles’ hard-edged designs, with blocks of acid colour and sans-serif type, stood out from both the heavy-serifs-plus-illustration look of most commercial design, and the unstructured agit-prop of Jamie Reid’s punk graphics of the period.

Eclectic inspiration

Incredibly prolific, Bubbles turned out a huge amount of work with great rapidity, designing everything from record sleeves to advertisements, from T-shirts to back-stage passes. Both Riviera and the musicians trusted him completely, accepting whatever he produced. For the Damned’s Music for Pleasure (1977), Bubbles co-opted Kandinsky. What distinguishes the device from many subsequent quotations from the early twentieth-century art is the humour and wit of the parody. Although at first glance it could be mistaken for a copy, hidden among the squiggles are schematic portraits of the band members and the word ‘The Damned’.

Bubbles made no secret of his sources of inspiration. His was visually egalitarian and anything was open to parody – fine art just as much as tat. ‘He didn’t see any difference between high art and junk,’ says Malcolm Garrett. ‘There was no difference between Mondrian in the Tate Gallery and fluffy slippers in Woolworths.’

Bubbles’ best work has its roots in an idea – whether funny, oblique or difficult – rather than in a trite pun on the record’s title. A good example is the sleeve for Ian Dury’s album Do It Yourself, one of his most audacious designs. He created and had printed 52 versions of the sleeve, each one covered in a different loudly patterned wallpaper. A simple idea, it is simultaneously one in the eye for good taste, a surreally pointless gesture, and yet ties in neatly with the record. There was also, of course, a slim chance that the more ravenous fans might buy all 52 varieties.

Post-punk disillusion

In the early 1980s, when punk had lost its idealistic anarchy and become just another marketing tool, Bubbles began to move away from graphic design into furniture design, directing videos (among them Ghost Town for the Specials) and fine art. He may simply have been disillusioned with the music business; he may have felt he was in his late thirties too old to be designing record sleeves. In an interview in The Face in 1981, he referred to up-and-coming designers: ‘They’re so creative the kids that do the sleeves – it makes me feel so staid and boring, and I think: I’ve got to get out, it’s time for me to go.’

Looking at Bubbles’ life and career, his excessive modesty seems to have been both a major strength and a tragic flaw. On the one hand, it prevented him from ever taking his word so seriously that he became pompous or closed to new ideas. On the other hand, his refusal to promote himself led to younger designers he had influenced inevitably stealing the limelight. Working freelance, charging comparatively little for what he did, and vague about paperwork and invoices, Bubbles did an enormous amount of work simply to keep the money coming in. Much of it was produced extremely quickly – and it shows. When he was on form, though, he was one of the first, best, wittiest, and most playful proponents of the recycled Modernist mix-and-match that went on to dominate graphic design in the 1980s.

Julia Thrift, design writer, London

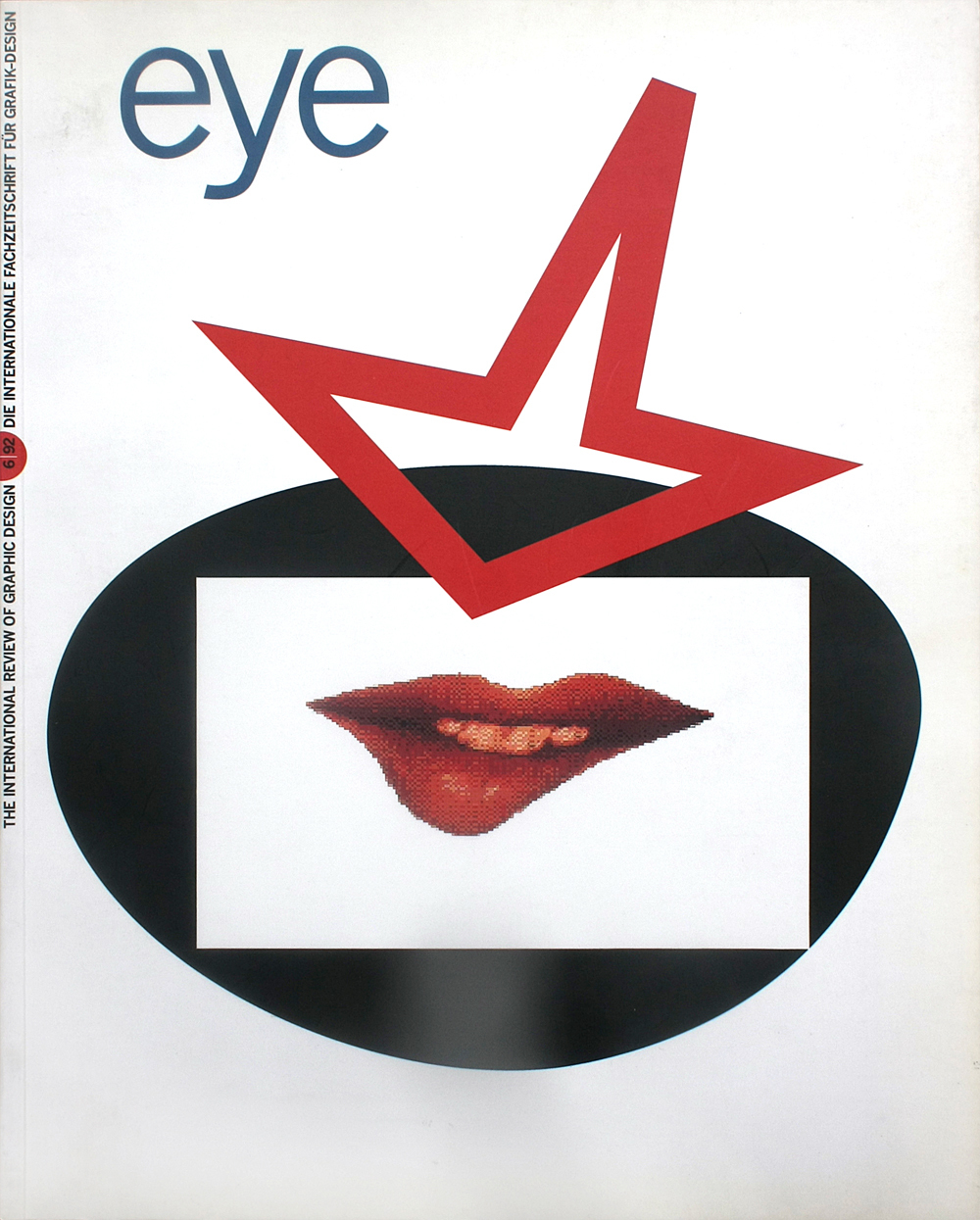

First published in Eye no. 6 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.