Autumn 2021

In the right hands

The work of Barcelona type designer Laura Meseguer is a beguiling alchemy of hand- lettering and digital craft. By Jan Middendorp. Photographs by Francesco Brembati

In the final decade of the past century – yes, the 1990s – young independent designers would mostly leave the digital updating of classic typefaces to the big companies. Individuals interested in type design were faster at re-exploring aspects of traditional techniques and deciding which facets of analogue typefaces and hand-lettering should be reviewed, improved, or replaced. Many of these new specialists were also more playful, less rule-based than the traditionalists.

This was very much the case in the graphic design and lettering scene in Barcelona around 1990, where artists and designers (but also those working in theatre, dance or fashion) produced works that were experimental, unorthodox and entertaining. Young designers who were fascinated by the new digital tools and techniques met and shared their discoveries. This is where Laura Meseguer’s typographic life began.

Born in Barcelona, Meseguer became fascinated by type and graphic design from an early age – she was the daughter and the grandchild of print shop owners. While it came as no surprise that she decided to study graphic design, the first course she took in the subject, in the late 1980s, was at a traditional academy, where early digital tools were yet to be adopted.

Laura Meseguer standing in front of Queviures Murria, an emblematic Barcelona shop that dates from 1903. All photographs by Francesco Brembati.

Top. Meseguer at work, 2021.

‘The curriculum consisted of various analogue lettering exercises’, says Meseguer, ‘like hand-drawing letters for a logo, or copying Futura with pencil and ink. While I was still a student, I was lucky to be hired as an intern by a graphic design studio. My first job was to work on a Repromaster [a process camera for reproducing graphics]. I had to reproduce the art director’s lettering sketches using Letraset dry-transfer sheets. I later realised how relevant that was – it made me quickly develop my knowledge of typefaces and composition. I learned how to compose type using a photocomposition machine and became pretty competent at it.’

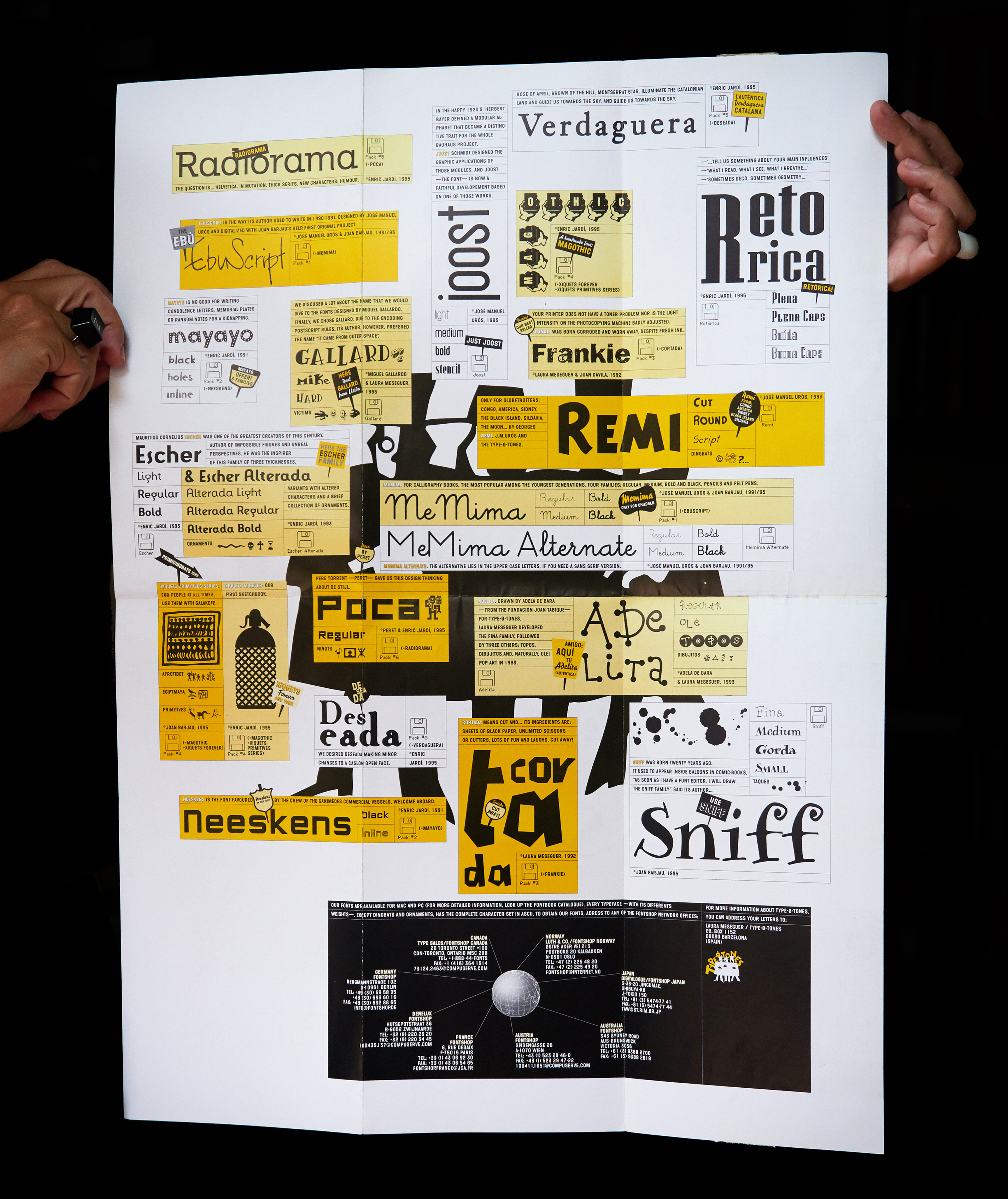

Type-Ø-Tones promotional poster designed by Enric Jardí for FontShop Benelux, 1996, which shows some of Meseguer’s early typefaces.

Yet Meseguer was fascinated by the new digital techniques. She became aware of a circle of young designers in Barcelona who were learning about Macintosh computers and software. Designer and musician Josema Urós had absorbed a lot about the new medium and had started to run informal courses for those who were keen to know more. He had met two adventurous designers intrigued by digital type – Joan Barjau and Enric Jardí – with whom he founded a trio that joked about the future of designing digital type. In 1990 – the same year in which Adobe made its exclusive Postscript font system available for free to independent type designers – Meseguer followed Urós’s lessons. When the trio became aware of Meseguer’s talents, she was invited to join Type-Ø-Tones – a collaboration that would soon become one of the first independent digital foundries in Europe.

In 1992, Barcelona hosted the Olympic Games, and young Europeans travelled there to be part of the splendid creative atmosphere in the city. One of them was Dutch designer and illustrator Max Kisman, who had created the first computer-designed postage stamps in the Netherlands. Having experimented with hand-cut alphabets in the mid-1980s, he became one of the first designers to publish digital fonts via FontShop’s collection FontFont, created by Neville Brody (see Eye no. 6) and Erik Spiekermann (see Eye nos. 18 and 74).

While in Barcelona, Kisman became fascinated by the quartet’s energy, humour and talent, and after introducing the team to FontFont, Typo-Ø-Tones became one of the first independent type studios. Meseguer was also one of the youngest female designers at the new font publisher.

Laura Meseguer in her Barcelona studio.

Grunge with historical roots

Meseguer’s first type design was pure experiment. Since she had not learned to draw curves on the screen, she drew the letterforms with straight lines only. She named the resulting typeface Cortada, Spanish for cut.

She created her second typeface while she was working at the advertising agency Bassat Ogilvy. Its client, Levi’s, wanted some ‘wasted’ lettering with historical roots, and the art director decided to work with Franklin Gothic, designed at the dawn of the twentieth century by Morris Fuller Benton for ATF (American Type Founders). Meseguer, collaborating with graphic designer Juan Dávila, created an early grunge font, which they named Frankie. In 1992 it won a silver Laus award. Once its exclusive use had expired, Frankie became an early Type-Ø-Tones display font.

Returning to graphic design, Meseguer was then hired by designer Pati Núñez. In 1994 Meseguer founded Cosmic Gráfica, a new design company with Dávila. The practice was small but innovative and enthusiastic, and made work for a broad group of clients, ranging from art spaces, music, theatre and performance shows to commercial companies – including paper manufacturers and wineries – who all appreciated Cosmic’s unorthodox attitude and styles.

Type-Ø-Tones remained a secondary activity for its members. But meanwhile they had produced dozens of fonts and type families, as well as attractive brochures. They received international attention through the FontShop catalogues. From the same angle came the online typographic magazine TypoRed, launched in the early 2000s in collaboration with three colleagues: Joan Barjau, Allan Daastrup and Mela Dávila.

Back to school

Meseguer was still serious about type design, but she felt that her technique and knowledge were limited. While the Type-Ø-Tones display fonts were well made and fun, their natural limitations frustrated her. She wanted to discover more about the type design world. Then she got the break she needed: in a guest article for TypoRed, the Argentinian type designer Alejandro Lo Celso mentioned various places where you could train in type design. Getting in touch with Meseguer, he suggested a postgraduate course which at the time was still not a ‘household name’ in the type world: the type design class Type and Media (known as ‘T]M’) at the KABK (Royal Academy of Art) in The Hague.

Personal, a letrazine, a sort of magazine designed and printed in Risography by Meseguer that presents three different connected chapters of her residence at the AGA LAB in Amsterdam, 2018.

Meseguer believed that a specialised curriculum and a full year on a Master’s course in type would help her to become a fully fledged type designer. In 2003-04 she joined the MA course at T]M. Apart from the hours spent at her father’s printing shop, she had never printed letterpress. ‘Not because he didn’t want me to, but because he was continuously busy. It was one of the crafts I would get experience with at Type and Media, like modern calligraphy and stone carving,’ she explains.

She was also introduced to the latest digital type design tools and techniques, and the curriculum’s main purpose – designing type though the type theory and design system that Gerrit Noordzij had developed in the twenty years he was the main typographic teacher at KABK in the 1970s and 1980s. Her graduation project, Rumba, was small, personal and highly original. The set of three fonts was based on handwriting shapes, with subtly different forms and contrast between them, each the ideal variation for a specific (and for the moment, still imaginary) use. She would perfect these fonts and release Rumba as her first conceptual typeface, both serious and charming. Later, in 2006, Rumba won a TDC award. In 2011, ATypI (Association Typographique Internationale) selected it as one of the 53 best typefaces of the past decade.

Rumba typeface family specimen, 2005. It comprises three fonts with varying contrast, construction and degrees of expressiveness.

Studying at KABK gave Meseguer great ideas and energy, and she hoped to stay in the Netherlands after she graduated. But she needed an income and could not find a job there. So she travelled back to Barcelona and set up as a freelance designer, focusing on type and lettering.

As well as learning about the history and recent development of printing type, her year in the Netherlands had stimulated Meseguer’s interest in hand-lettering on book covers, magazines and posters.

‘My first love for the medium and tradition came after discovering Helmut Salden [the designer who escaped from Nazi Germany in the late 1930s and became the Netherlands’ most productive and original book designer after the Second World War] and the books by Gerrit Noordzij. Later I expanded my love to lettering artists such as Michael Harvey, Paul Rand and others, and I started collecting their books.

‘In Barcelona, I learned about the local, mid-century hand-lettering scene. That was a logical expansion of my love for lettering. At some point I did a research project about my personal fascination with the lettering work of Ricard Giralt Miracle.’

Meanwhile, the Type-Ø-Tones type foundry had built up a versatile library. Two of its original founders had gradually moved away to concentrate on other areas of design; the company was now a two-person enterprise run by Meseguer and Josema Urós. In the early 2010s, she produced her first extensive typeface family – Multi. The original assignment came about through her contacts in the Netherlands.

Multi Display, 2011-2016.

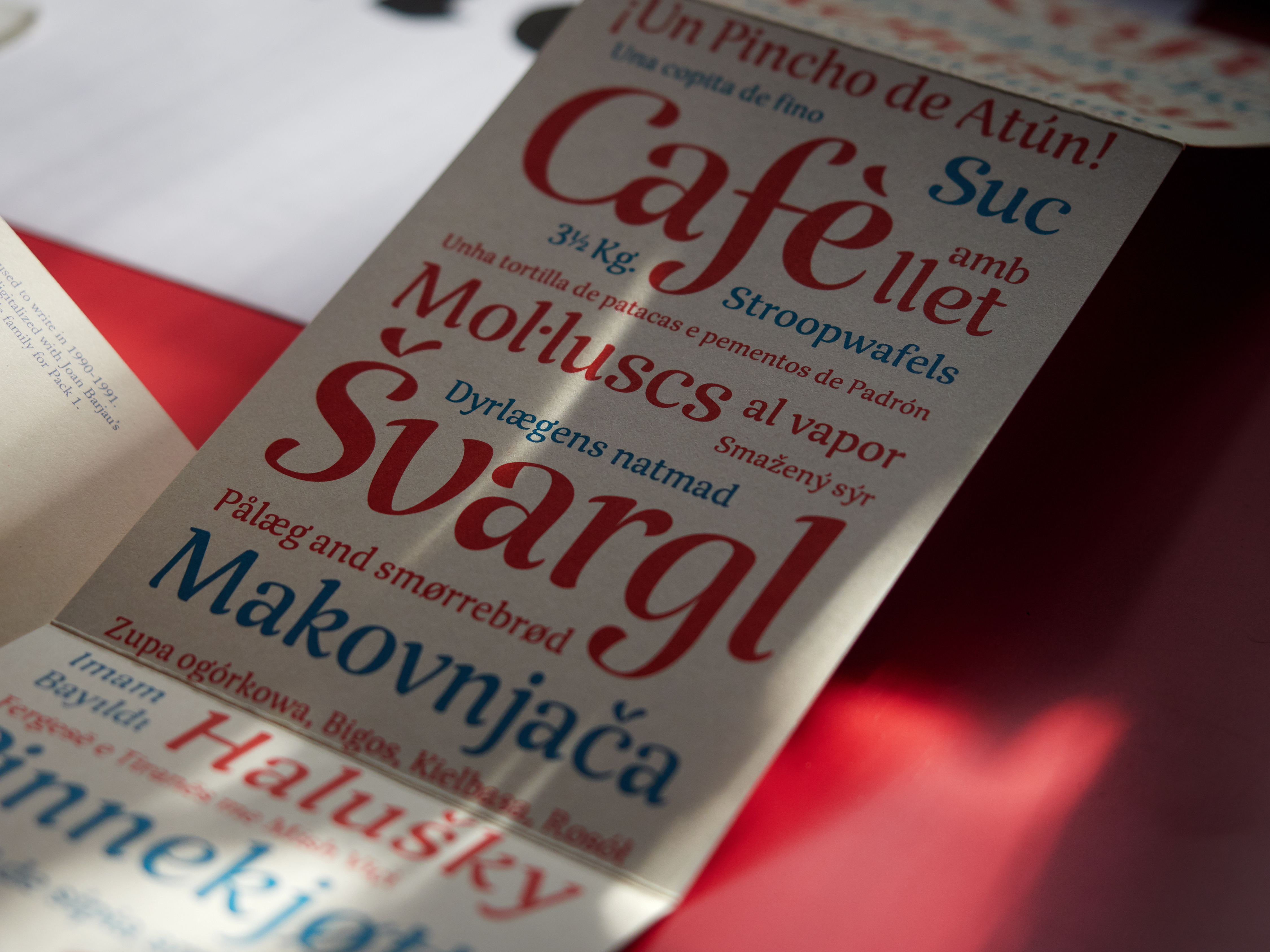

Meseguer says: ‘It was commissioned by a publisher of Dutch regional newspapers in 2011. The goal was a comprehensive layout overhaul project, supervised by editorial art director Luis Mendo (for years the Spanish designer was one of the most influential magazine designers in Amsterdam, and eight years ago started a new life as an illustrator based in Tokyo). The client provided an unequivocal series of test words: warm, dynamic, optimistic, friendly, human ….’

Mendo was convinced that Meseguer was the right designer to visualise those ideas. She designed two series: Multi Text (two weights, roman and italic) and Multi Headline (six weights, roman). After five years of exclusive use by the client, Meseguer’s foundry could introduce this font family to its own catalogue. ‘I considerably expanded the character set and the family, and implemented a few modifications. Multi Text now comprises three weights (each roman and italic); the Headline was renamed Multi Display: seven weights, all in roman and italic.’

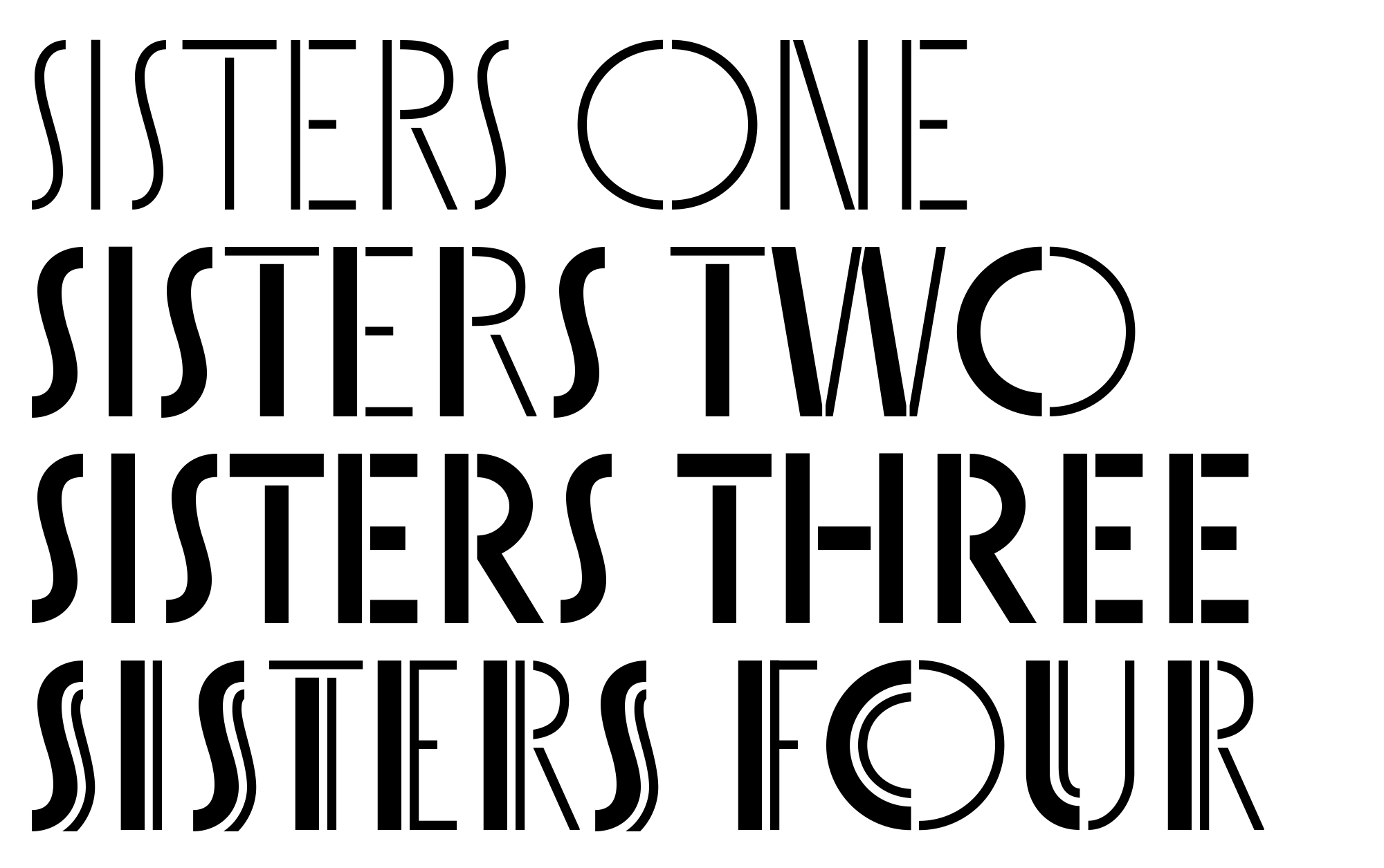

Sisters, 2020.

She continued producing personal display faces, often inspired by mid-century lettering — the ‘wavy’ yet semi-geometric Magasin (2013), Lalola (TDC winner, 2014) and the four-strong capitals-only set of Sisters: ‘four fonts that share foundational principles of construction yet complement each other – as sisters do – by celebrating their differences.’ Meseguer’s hand-lettering and logo design projects also expanded into a broad series of original designs.

A book that became a classic

When Meseguer began to teach on graphic design degree courses, she realised that some subjects were poorly covered. One genre she found little material about – and none in Spanish – was magazine design. She got the opportunity to write a book on the theme with Spanish publisher Index Book. One of her former students, Floor Koop, a Dutch student who travelled to Barcelona to learn more about type design, had become a designer there. With the help of Koop and Claudia Parra, her assistant at that time, Meseguer produced a book that became a classic, TypoMag: Tipografía en las revistas.

From an initial selection of 200 magazines, the team narrowed down their list to 29, and each magazine is shown extensively and analysed. The book received a Laus Award in 2011. It was translated into English as TypoMag: Typography in Magazines and received international recognition.

Meseguer’s next book project was a collaboration, Cómo crear tipografías: Del boceto a la pantalla – a Spanish-language guide to type design (see ‘On being well read’ in Eye no. 84). Her partners in this were two other type designers, Cristóbal Henestrosa in Mexico and José Scaglione in Argentina. The book consists of individual chapters that clearly demonstrate the collaboration of three type designers with different experiences, but with similar attitudes towards type design and teaching in ‘… a straightforward and direct way’. First published in 2012, the book’s original Spanish edition was a worldwide success and was reprinted a couple of times. From 2014 there was an English version, How to create typefaces: From sketch to screen (see ‘Typographic Noted no. 82’ on the Eye blog).

Het Parool titlepiece, 2015.

One of her most visible and permanent assignments was a logo for Het Parool, a daily paper in Amsterdam. It had been founded as a socialist resistance paper in February 1941 during the German occupation. Having produced the Multi newspaper type family a few years back, Meseguer was now invited to redesign Het Parool’s masthead. Dutch designer Floor Koop, who had worked on Meseguer’s Index magazine design book when in Barcelona, was now at the newspaper. She conducted the 2016 redesign together with John Koning. They made two proposals, both based on the classic bold serif title: one subtly classic; the other sharper and more modern. The newspaper’s team liked both, and commissioned Meseguer to design a version to connect these contrasting styles.

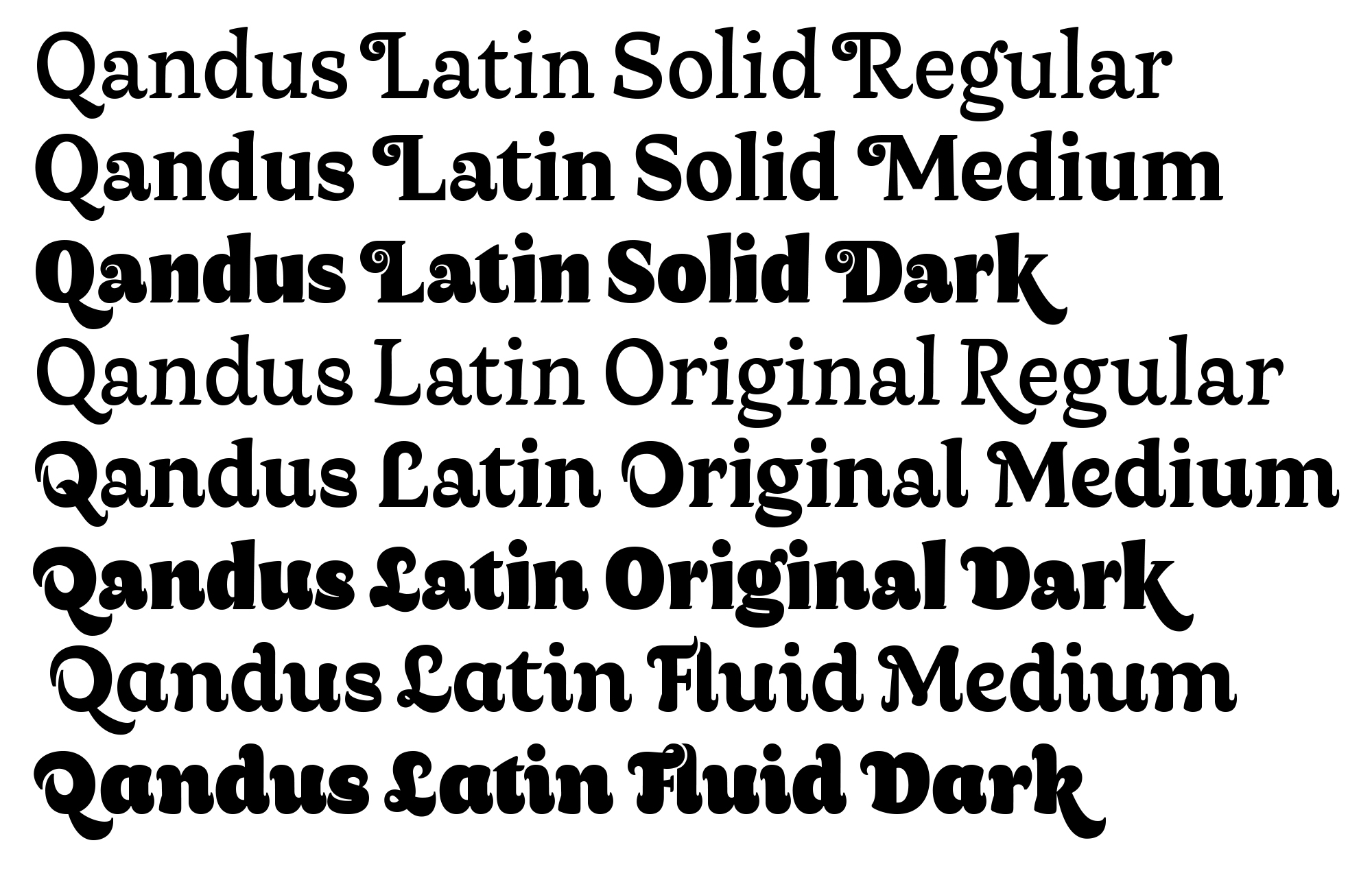

The collaborative Qandus pluri or multi-script family (2015-17) was part of a complex project called ‘Typographic Matchmaking in the Maghrib’, in which various groups of type designers met in Marrakesh, in North Africa, in 2015. Developed within the framework of the Khatt Foundation’s type design research project curated by Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFarès, its purpose was to create a modern typographic interpretation of the Maghribi style of the renowned, nineteenth-century Moroccan Sufi calligrapher Al-Qasim al-Qandusi.

Qandus, 2015-17.

The designers involved were Meseguer (Latin), Kristyan Sarkis (Arabic) and Juan Luis Blanco (Tifinagh, an ancient script used to write the Amazigh or Berber languages) and the result was a large collection of scripts. Among other awards, the Qandus family won the TDC 2017 Award for Excellence in Typeface Design.

In 2018, Meseguer had an opportunity to move back to the Netherlands for several months. The artist-run printmaking space AGA LAB invited her for a graphic artist residency that would take place in Amsterdam – the city she had loved most during her course at KABK (less than 70km from The Hague). For a period, she could move away from the Spanish commercial scene and explore printing tools that she had hardly worked with before.

‘I had access to different printing techniques – silkscreen and Risography being the ones I used most,’ she says. This stay led to the idea for an exhibition entitled ‘Expanding the Craft’. At the same time, she collaborated with the ceramicist Sophie Eekman, producing a series of ceramic artworks. Short texts produced with the three scripts of the Qandus multi-family were used as visual material for usable plates and bowls produced according to traditional techniques by Eekman. ‘The inspiration for these pieces was born from the realisation that we are living in a time where we are witnessing the highest levels of refugee displacement on record,’ says Eekman.

Deep knowledge

Back in Barcelona the following year, Meseguer collaborated intensively with type colleagues Noe Blanco, Joancarles Casasín and Oriol Miró on Tipo-g – a new Barcelona School of Typography which opened in October 2019. They wrote: ‘In the new era, graphic design has been diluted in a great diversity of fields of application… But we believe that it is essential to have a deep knowledge … about typography to be a good graphic designer. Tipo-g addresses this need from a rigorous, creative, open, and ever-evolving perspective.

‘It is a “free” school in the sense that it does not depend on any university or educational organisation. So we do not offer a degree, but a new intense and immersive educational experience and a space in which to learn, experiment and debate about typography and type design, and its application in the various environments of today’s communication.’

Towards the end of 2020, Meseguer’s internationally growing influence was rewarded with a solo exhibition titled ‘The Beautiful People’, produced at the art centre La Sala de Vilanova i la Geltrú in southern Barcelona. The concept came from curator Eider Corral, a graphic designer from the Basque Country, who curated and designed the show with Meseguer.

As the event’s website explains: ‘The Blanc! Festival (part of the Centre’s Blanc-Orígens programme) dedicates an exhibition to the modern letters of Laura Meseguer – the first female designer to be presented as such.’ The exhibition was an interesting mixture of type design, lettering and calligraphy on the one hand; and on the other, a story about (and analysis of) her collaborative typeface project Qandus.

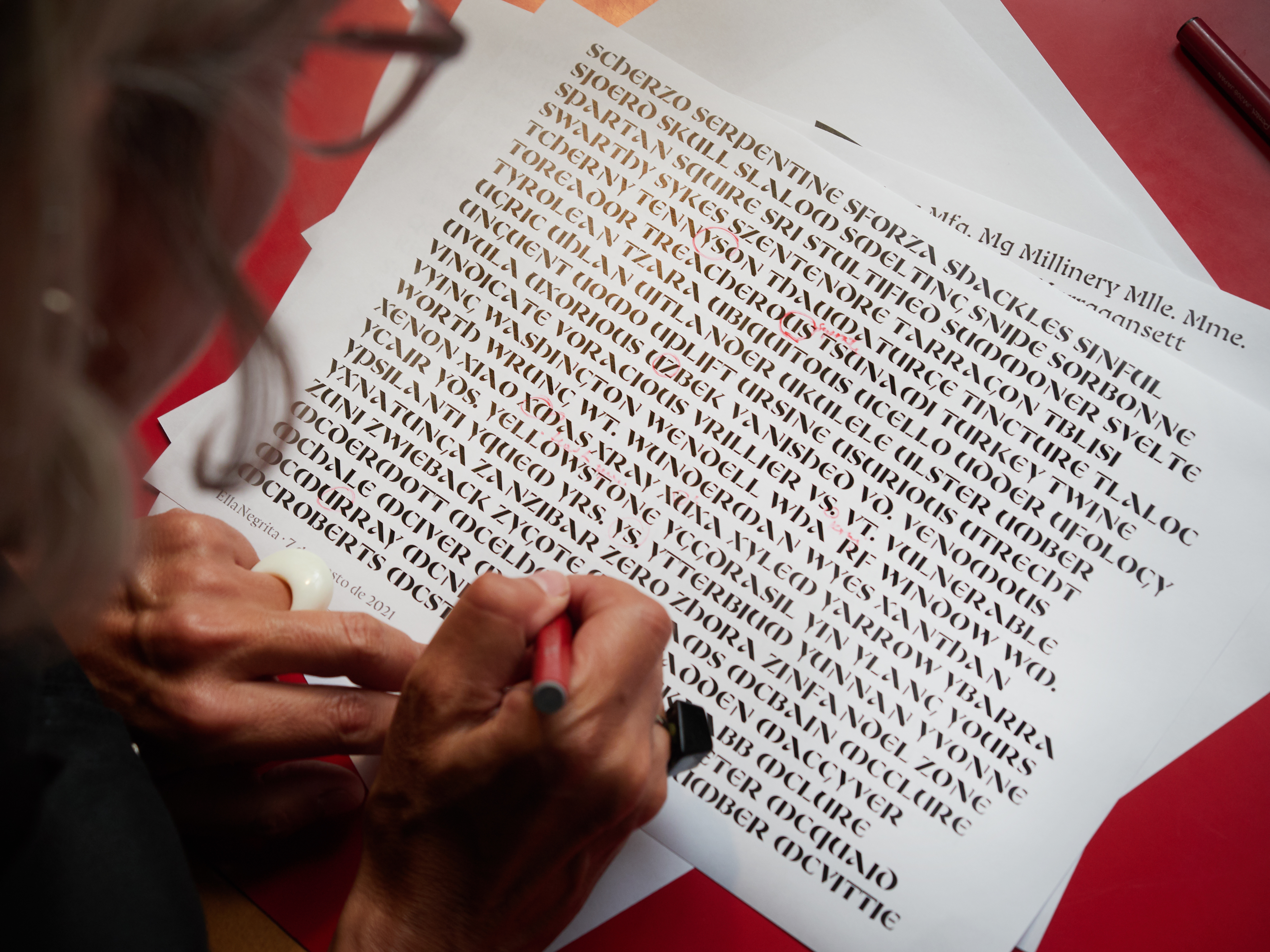

Proof testing of Ella Uncial Bold typeface.

Meseguer’s most recent typeface, Ella, will enter the market in 2022. A font suite in four type families, Ella refers to very different elements. Her recent work is mostly based on hand-lettering and type, and questions how they are modified into a digital project. Another reference is the history of stencil letterforms, used in hand-lettering from Medieval church books to metal signs. Style wise, the four Ella families absorb and summarise styles from the traditional period between hand-written book copies and the Western invention of type.

There have recently been similar projects – such as the conference and exhibition at the ANRT type research institute in Nancy, France, and Gotico-Antiqua, a voluminous, multi-author catalogue that came out recently (see ‘From gothic to roman, almost’ in Eye 102. pp. 98-99).

But Meseguer’s Ella project was a personal initiative first developed during a residency (Mujeres Hispanas y Tipografía) at the Hoffmitz Milken Center for Typography in early 2021. She later developed its shapes with the input of two respected Barcelona calligraphers, Oriol Miró and Laia Soler. Apart from the historical and technical themes, Meseguer speculates about the link between unconventional, yet century-old transitions from straight lines to curves in her explorative Ella and the architectural style of Brutalism. Ella’s beguiling characters form yet another chapter in Meseguer’s fascinating career.

Jan Middendorp, designer, writer and author of Dutch Type, Berlin

Ella, 2022.

Façade of former fabric shop El Indio, dating from 1913, which finally closed in 2014.

Mosaic lettering at Amadeo Carbonell, the fully restored premises of a 1920s electrical and plumbing installation company, now used for events and pop-ups. Note the rounded terminals of the serifs. ‘The more I look at this, the more I discover,’ says Meseguer.

Mosaic lettering for Farmacia Laboratorio, 1925, by Lluís Brú i Salelles (who also did ‘Luz’, above). The pharmacy closed in 1987 and is now a plant shop.

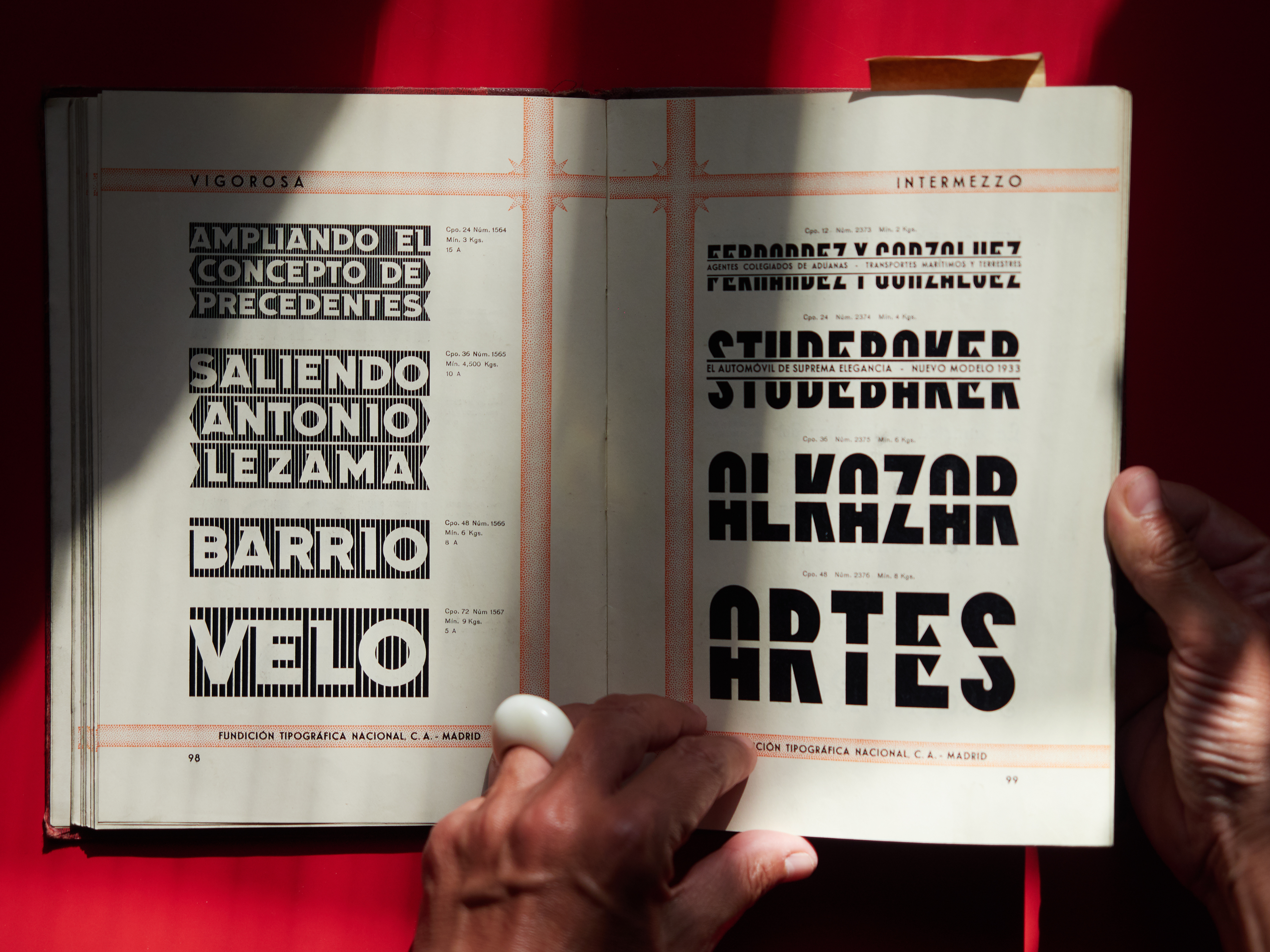

Spread from a specimen published by Fundición Tipográfica Nacional, 1935. Founded in Madrid in 1915, the Fundición Tipográfica Nacional was for many years the leading Spanish type foundry, with innovative designers such as Carlos Winkow and Enric Crous-Vidal, known for their Art Deco typefaces.

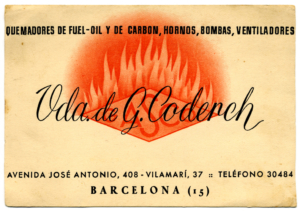

The business card of Meseguer’s grandfather Antonio Meseguer, Impresor (printer), ca. 1950s.

A typical job printed at the Meseguer family’s letterpress print shop in central Barcelona.

First published in Eye no. 102 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.