Winter 1994

One step nearer full-screen video

Software: QuickTime's upgrade

Brett Wickens on QuickTime’s upgrade

If messages on the Internet are anything to go by, you would have thought Apple was in the process of developing a secret weapon earlier this year. QuickTime (QT) 2.0 was on everyone’s lips months before its release. Whispers of our forthcoming capacity to play full-screen, full-motion video on our Macintoshes abounded.

Unfortunately, like the children’s game Submarine, where messages are relayed from one person to another until they are no longer accurate, QT 2.0 became a victim of the misunderstandings that accompanied its advance publicity. If you want to capture, edit and play movies on your Macintosh, you need expensive additional hardware. Software compression and decompression, though inexpensive, will not in most circumstances enable you to do much more than view the postage stamp-sized movies we have been accustomed to since the appearance of QT 1.0.

In fairness to Apple, however, QT 2.0 is a substantial improvement over previous versions, and a host of new applications and utilities have become available to facilitate the process of making movies in the QT format. The single biggest improvement lies in the QT DataPipe. Simply put, this allows QT to manage the processing functions of the Macintosh during the playback of QT movies more effectively. Moves can now be made which take full advantage of the playback device. In most cases this will be a CD-ROM drive, and in the case of the double-speed Apple CD300, the movie can play back data at 300k per second instead of the previous 200k.

Apple insists that full-screen, full-motion playback can be achieved on regular Macintosh equipment without additional hardware. This claim has some significant caveats. First is the configuration of the playback machine. The biggest limiting factor for movie playback is the performance of the video memory. NuBus video cards are much slower than on-board video memory. Almost every practising designer I know uses third-party video cards to drive their monitors, primarily because these address issues of speed in other areas, such as screen redraws in Adobe Photoshop. Not using the on-board video for QT playback gives disappointing results. In the case of AV Macintoshes, you cannot even record video from external sources without using the on-board video, because the video digitising circuit uses the video memory and is activated only in the presence of a monitor assigned to that port.

Second, the ‘playback’ size is a qualified measurement. Adequate movie playback can be achieved on most Macintoshes using a 320 x 240 window. This is about double the previous size, but only half the size of a full-screen monitor. By ‘pixel-doubling’, the move can play back at 640 x 480, but each pixel is doubled in size and therefore halved in quality.

Third, optimum playback results when other elements are not vying for the attention of the Macintosh processor. Such things as AppleShare and virtual memory should be disabled – and it does not hurt to stick a floppy disk in the drive so the processor is not constantly looking of the presence of a disk.

Despite these limitations, working with QT has never been easier, especially using the new PowerPCs. With the QT PowerPlug installed, compression of movies runs at between 2.5 and four times faster than on a Quadra 950. Also, QT is capable of reading digital video in the MPEG format directly from Philips CDi disks. MPEG is an emerging standard for storing video on CD disks, and a number of Hollywood titles are now available in this format for use on Philips CDi players. With the latest Apple CD-ROM system extensions, you can now watch these on your Macintosh.

On the QuickTime Developers CD (available from the Apple Professional Developers Association) are a number of new or updated utilities for creating, editing and modifying QT movies. One difficulty in preparing QT movies is optimising the colours shown when playing the movie back on an 8-bit monitor. Most clour monitors in use are 8-bit, and are capable of displaying on 256 clours at any one time on screen. But most designers use 24-bit screens, capable of displaying photographic-quality images. To achieve the best-looking playback, it is necessary to create a ‘colour-lookup’ table (CLUT) of the 256 most prevalent colours in your movie, than install the CLUT in the movie using the ‘Set Movie Color Table’ utility. When playing back on an 8-bit monitor, QT will use the nformation to achieve the most aesthetically pleasing results. An Apple utility entitled ‘Make Movie Color Table’ is available for ‘polling’ the movie to determine the best subset of 256 colours, but DeBabelizer from Equilibrium is a far superior program that will do the same thing.

Another significant feature of QT 2.0 is its handling of sound. Direct support of the MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) standard has been implemented and Apple has licensed musical instrument samples from Roland that can be used as part of the movie’s soundtrack. AIFF files, the prevailing standard for sound files on the Macintosh, can be opened directly as QT movies with the Apple-supplied MoviePlayer 2.0, and can be controlled using the standard movie controller. The direct importing of audio CD tracks is supported, as is 16-bit stereo sound.

There is much competition at the moment to create optimum video CODECs (compression / decompression standards). When companies want to send digital video through interactive cable boxes to your living room, they will be relying on a CODEC to squeeze all the information through the wire and into your television. Similarly, there are plans in Hollywood to dispense with the arcane process of ‘printing’ film and delivering reels to cinemas. Instead, compressed digital images will be transmitted in real time via satellite to each cinema.

It

seems safe to suppose that QuickTime 2.0 will not be used for either

of these purposes – perhaps QuickTime 8.0, when it is invented. In

the meantime, the postage stamp-sized movies we impress IBM users

with have become a little faster, a little bigger and a little

smoother. But if you make your living from working with motion

graphics and digital video, look to something like the Radius Video

Vision Studio to add to your Macintosh set-up. That will provide real

full-screen video.

Brett Wickens, Multimedia director, Los Angeles

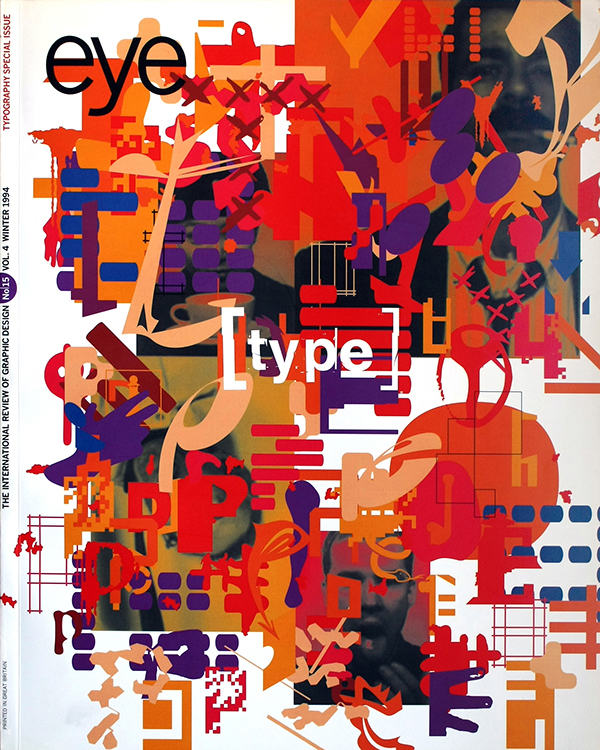

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.