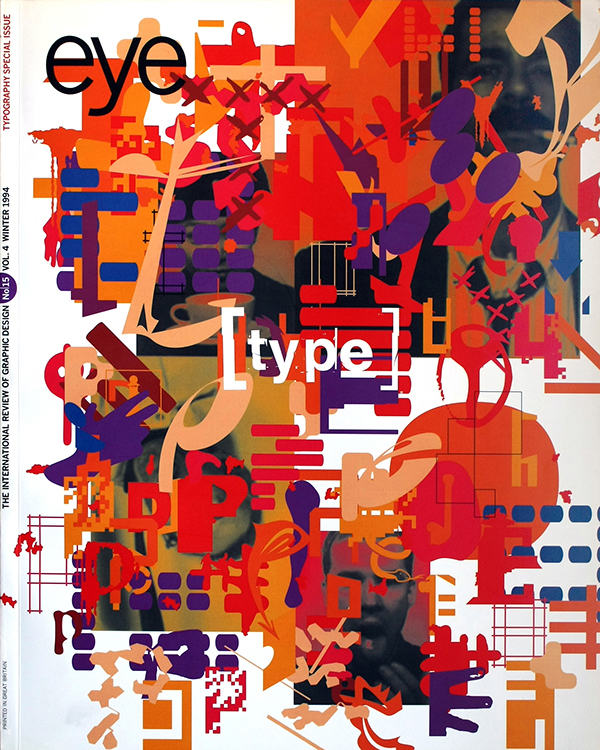

Winter 1994

The producer as author

For Toronto designer Bruce Mau, graphic design more than mere design. He sees his work as a way of exploring ethical, cultural and philisophical issues. Should we rethink our ideas of authorship?

Two years ago, a Toronto newspaper ran an article on one of Canada’s most iconoclastic designers entitled ‘Chairman Mau’. The subject of the piece was Bruce Mau, and the headline was meant to draw attention to his image as an outspoken critic of contemporary design practice. It must have hit its mark, because Mau took exception to the gag, feeling that it unfairly cast him as a disgruntled enfant terrible practising on the lunatic fringe of the profession.

Mau earned his media spurs as the designer of Zone, the acclaimed series of volumes on urbanism and philosophy edited by Sanford Kwinter, Jonathan Crary and others. He had spent the early 1980s working for such firms as Pentagram in London and Spencer Francey in Toronto, but was unhappy in the mainstream. By mid-decade, he has helped launch a new firm called Public Good, which specialised in work for public and no-profit-making organisations. When the opportunity to design the first issue of Zone presented itself, Mau was eager, but his partners were not. They split, Mau took Zone, and his career as a highbrow designer was on its way. The five volumes published since 1986 have opened doors for him all over North America and Europe, from the Getty Institute in Los Angeles to I.D. magazine in New York, and the National Architecture Institute in the Netherlands.

Now that Mau has established an international reputation in artistic, architectural and intellectual circles, he seems less sensitive about his image than he was two years ago. When we recently met to review his current work, he was wearing a souvenir lapel pin from the Republic of China, emblazoned with the smiling countenance of the real Chairman Mao. Whether this was a token of apostasy or a camp accessory is hard to say. But what did become clear as we talked was that Mau cannot discuss either his projects or his practice without ideological rigour. The work is not addressed as mere design; it is treated as a vehicle for the examination of ethical, philosophical or cultural issues of a kind usually associated with academic research.

One of these issues is the role of the designer in the formulation of content. According to Mau, ‘Content is no longer necessarily outside the realm of design practice. What I am trying to do is to roll Bruce Mau Design on to the field upon which content is developed.’ To illustrate how this paradigm of shared authorship might work, Mau states that in the normal course of project development, the ‘author’ is the one who enjoys the luxury of penetrating the depths of the subject, of pursuing ideas down any and all paths of speculation, no matter how long or labyrinthine. The designer’s involvement is expected to be brief and to occur within a very shallow range of exploration. After all, the important work has been done: the designer’s job is simply to provide a package. Mau wants to take ownership of the front end of this process, preferring the rigours of intellectual discourse to a relationship in which ‘the designer leads a kind of karaoke existence, always singing someone else’s song, and never saying what he thinks should be said.’

But there are difficulties awaiting those who try to take over this terrain. One is that the pricing structures and client expectations within mainstream design practice are based on the designer not being involved in the content. Unfettered speculation tends to upset budgets and schedules, and most client/authors would regard the designer’s intervention in the formulation of content as presumptuous.

Perhaps more importantly, there is the old problem of form versus content. Can the form given to a text by the designer be considered content, as primary and meaningful as the text itself? Even if one accepts design as a rhetorical practice, capable of enhancing or even reframing the text, does such power convey the mantle of authorship upon its executors?

These issues are brought into sharp focus by one of Mau’s most recent projects, a huge tome entitled S,M,L,XL, done in collaboration with architect Rem Koolhaas. What started out as a standard monograph on the work of Koolhaas’ studio OMA has evolved into what Mau calls ‘a kind of novel about architecture.’ More like a collection of short movies, it turns the history of Koolhaas’ practice into a cinematic soup, brimming over here with the explosive urgency of Buñuel’s Un Chien andalou, bubbling over there with the indignation of Marinetti’s Futurist manifestos.

At first sight, the degree of Mau’s editorial intervention seems to indicate that he has taken great liberties with the text. There are brilliantly designed passages: a lavishly long sequence of views of the Rotterdam Kunsthal II overlaid with a passage from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot; 22 pages of photographs of Koolhaas’ book Delirious New York with an excerpt from the text set large across the middle of the whole sequence. But a reading of the book, written by Koolhaas and two of his editors, reveals that the design is no more eccentric or adventurous than the text. Thus the designer has not so much advanced a point of view as emulated that of the author.

Given its size – some 1400 pages – it is safe to say that Mau has created nothing less than a monument to Koolhaas. When asked how the project could possibly have grown so large, Mau replies, ‘When you develop content in this way, you have to assume a kind of “surfing” posture, because the thing is constantly mutating. You are creating a very intense collaborative space with the author in which you are inventing thins that neither one of you is in control of. But that’s the beauty you are destroying the whole potential of the process.’

Within mainstream design practice, this process would have the potential of destroying a studio. Indeed, when I arrived at BMD to get a preview of the work, the entire staff was engaged in getting the project out of the door – and would continue to be so for a week longer. I was later informed that this was how most of the book was executed. Koolhaas would camp out at the studio, and for five or six days everyone would work a 12-to-16 hour day developing the ideas proposed by the chief collaborators. Mau’s defence of this managerial nightmare is that you get a depth that it is impossible to generate in any other way.

Whether he is talking about intellectual profundity or just the luxury of having an endless supply of fresh horses, it was the willingness to go to such extremes that kept Koolhaas happy throughout the process. But how do you keep the business profitable under such conditions? That job falls to Lee Jacobson, who joined the firm in a managerial capacity about a year ago. ‘This was not a financially feasible project. We treated it as R&D, and were willing to finance it through profits earned on other projects, because we believe it will have enormous value in promoting the company.’ This is BMD’s preferred approach to getting new work. Through Jacobson admits to doing some selling, Mau’s theory of business development is based on the idea that the work you do creates your future, and the more you can let that happen of its own accord, the better your future will be: ‘You have to let the engine run itself. The most difficult thing is to take your eye off the projects in order to sell- as soon as you do that, you can’t do the projects well. The projects are your best sales tool.’

Another of Mau’s sales tools is architect Frank Gehry. Gehry seems to have anointed Bruce as his design acolyte, bringing him along as a typographic standard-bearer on some of his most interesting projects. One such collaboration is the Walt Disney Concert Hall, soon to be home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic. For this assignment, in which Mau was charged with developing the building’s typographic signature as well as its directional signage, a font was designed with chaotic idiosyncrasies that are only visible close up; the further away you move, the more ‘regular’ (and legible) the font appears. The designer who created it – Greg Van Alstyne – describes it as a ‘mix of reason and insanity’. He explains, ‘At Bruce Mau Design there is a tendency to strip type down to its bare essentials. We started with News Gothic, but it seemed to lack personality. I argued that since the concert hall had such a strong sense of Zeitgeist, we might as well abandon some of the Modernist discipline and apply a more exuberant logic – almost like Hector Guimard did with his entrances to the Paris Métro.’

Whatever its expressive nature, the signage nevertheless had to comply with the rules enshrined in a recently passed law called the ‘Americans with Disabilities Act’ or ‘8oA’, Law 8oA governs all public signage and dictates such values as x-height to cap-height ratios, the ratio of stroke width to letter width, chromatic contrast between foreground and background, and when to use upper or lower case. Working within such strict parameters, Van Alstyne still managed to create a font full of subtle surprises, about which Mau says, ‘the more you look, the more you see’. Whether or not concert subscribers will have the patience to appreciate such a subtle rendering of typographic entropy remains to be seen.

Another introduction by Gehry led BMD to the door of EMR, a regional electrical power authority in Germany. While working on the directional signage for the organisation, BMD was asked to come up with suggestions for dealing with an oddly shaped room. The studio’s response was to develop an exhibition programme called ‘The Culture of Energy’, which positions the production and consumption of energy as a cultural rather than a technical problem. ‘In the course of our research,’ says Mau, ‘we realised that our orientation to energy and the way that we live as a result is primarily a cultural condition. The problem becomes aligning our culture with our energy requirements. For example, if your concept of urbanism is Los Angeles, and you export that concept around the world, you had better go into Iran and take over the oil fields, because you are going to need them to build cities that depend upon auto traffic.’ This line of thought led the Mau team to consider everything as an energy exchange, and to embrace all kinds of subjects as potential exhibition material. One display will be called ‘The Poetry of Weather’, complete with a ceiling-height tornado; another will focus on energy consumption in the home and will feature a house full of appliances mounted on the wall, perpendicular to the floor.

When asked how difficult it was to make the shift from printed page to exhibition design, Mau points out that most of his staff are trained as architects, not graphic designers, so the transitions was easy. He prefers graduate architects because of the intellectual rigour of their training, something that is sorely lacking in most graphic design curricula. But what about architects’ approach to the printed page? ‘They tend to think of the movement through space as a series of events,’ explains Mau, ‘so applying that to the sequencing of book design seems a natural extension of their discipline.’ The result in the books designed at BMD is more cinematic than architectural. Mau counts film-makers among his principal influences, particularly Sergei Eisenstein and Chris Marker. His juxtapositions of contrasting colour and imagery reveal and understating of the montage effects pioneered by Eisenstein, who claimed that the collision of two independent, even opposing shots produces a unique synthesis in the mind of the viewer. Mau has used this device time and again, most recently in the introductory sequences of Zone 6.

His willingness to dwell on one visual subject to the point of hyperbole reflects his interest in Marker, who once opened a documentary film on Akira Kurosawa with a full-frame close-up of the director’s face that lasted for several minutes without a change in camera angle. In the S,M,L,XL book, there is one sequence of shots of a house outside Paris that lasts for 50 pages; in an I.D. magazine article on Frank Gehry’s ‘Hockey’ series of bentwood chairs for Knoll, Mau persuaded the editors to publish views of 115 prototypes, a sequence that went on for seven pages. As I.D. editor Chee Pearlman puts it, ‘Bruce is not one to be burdened by what he considers to be petty constraints.’

In a corporate identity project for the NAI (Netherlands Architecture Institute), the notion of visual excess is taken to a kinetic extreme to demonstrate that an organisation with a commitment to diversity need not be constrained by a monolithic mark. In opposition to the classic Modernist approach to corporate design of one company, one logo, BMD proposed a concept expressed by the slogan, ‘100 logos and 1000 colours.’ The letters NAI are projected at several angles on to, into or through different surfaces. Different projections are then reproduced on different pieces of stationary in different colours. Since the projected image is what is printed on the final document, and the origin of the projection is never reproduced per se, the identity is, in effect, never seen this replacement of the monolithic with the morphogenetic seems to sum up the cultural agenda at BMD. At a time when multinationals are feverishly building brand equity by imposing a single trademark on a diversity of products, Mau is testing the potential of brand fragmentation by giving a single client several different trademarks.

One may rightly argue that such speculation is only possible in the rarefied terrain of BMD’s market: arts organisations, rogue architectural practices, academic institutes and esoteric publishers. Certainly Mau’s brief tenure as creative director at I.D. magazine suggests that he found it difficult to work within the conventions of commercial publishing. It is not something he likes to discuss, but when pressed, he is honest about why the relationship failed to work out: ‘I guess in the end the problem was that I wasn’t the editor.’

As editor Chee Pearlman tells it, ‘At the time Bruce was hired, the new owners were looking to create a design magazine that broke the rules. Of the seven people we interview, Bruce was definitely the most opinionated and iconoclastic.’ Pearlman goes on to explain that since Mau had never designed a magazine before, he was totally unencumbered by the conventions of magazine publishing. Readers will recall the cool minimalism he brought to the layout, giving it an almost bookish quality. ‘He gave us a distinct personality, and broke us away from everyone in the design pack. But the daily logistics of making a magazine became too much of a constraint. In the end, he resigned, but I think we all realised that it was too difficult to produce a magazine under those conditions.’

It would appear that Mau need the luxury of projects like S,M,L,XL to hit his stride as a designer and to satisfy his desire for authorship. But can the designer be construed as an author? ‘No way,’ asserts Nigel Smith, Mau’s longtime associate and now a competitor. ‘S,M,L,XL started when Bruce was a child- there’s 25 years of Koolhaas’ architecture in there. It’s not about Mau, it’s about Koolhaas. The author is the person who creates the text. You can’t claim authorship because you made the page pink.’ Jennifer Sigler, one of Koolhaas’ editors and project co-ordinator of S,M,L,XL, disagrees. She believes that the cinematic structure of the book is all Mau and that that makes him an author, thus implying that design is a powerful form of rhetorical intervention. It is a reiteration of the classic debate on the relationship between rhetoric distorts the truth, while Aristotle took the position that through and the form in which it is expressed are indivisible.

At the end of the day, one must remember the sequence of events. In most cases, the content is created first and the form comes second, as a response to that content. One could paradoxically argue that close collaboration with the author in the generation of form makes the designer even less of an original creative voice. In the case of S,M,L,XL Koolhaas not only made the architecture and wrote the text, but heavily intervened in the design as well. Will the real chairman please stand up?

Will Novosedlik, graphic designer, Toronto

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4, 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.