Wednesday, 8:00am

13 May 2015

Beyond selfish

Could Selfiecity’s systems of visual analysis one day become a force for the common good?

‘Selfies’ are a cultural phenomenon, and it seems you cannot move for people taking them, writes Noel Douglas.

Barack Obama, David Cameron and Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt posed for one at Nelson Mandela’s funeral. Astronaut Chris Hadfield smiled for the camera while floating in space. ‘Selfie’ was the Oxford English Dictionary’s ‘word of the year’ in 2013. And now there is Kim Kardashian West: Selfish (Rizzoli, $19.95), a book consisting solely of selfies.

But are selfies a blight, reinforcing the social media-driven narcissism of modern branded culture, or are we missing some of the subtleties and complexities of the way these images are used and consumed?

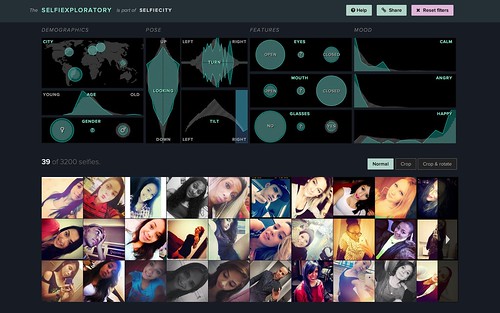

An analysis of the right head tilt based on the demographics, pose, features and mood of the selfies that were part of the study.

The website Selfiecity promises to enlighten us by analysing hundreds of thousands of Instagram selfies from five different cities – New York, Sao Paulo, Berlin, Bangkok and Moscow. The artist, designer and media theorist Lev Manovitch led the team, at City University in New York, that produced the site. The project has two halves: the actual analysis of selfies, and the development of tools to analyse such a large array of images. With a dataset so big and with so many variables, the makers could only hope to capture some of what these images might be telling us.

The biggest challenge, according to Moritz Stefaner, one of the designers, ‘was to find forms of summarisation that show the high-level patterns in the data – the big picture – but still respect the individuals, and don’t strip away all the interesting details. Turns out, you can’t just average images and expect interesting results.’ So how do we create tools that allow us to understand the huge networked image collections that are made possible by the net?

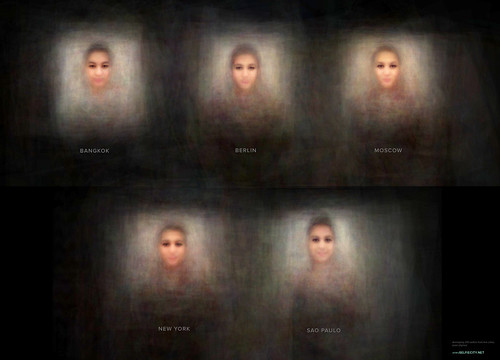

The picture shows 256 images from each city, eyes aligned, each drawn with 1/256 opacity. Stefaner says: ‘Note how the averaging algorithm introduces a Virgin Mary look – an aggregation artefact. Or, in other words – the sum of selfies does not look like a self.’

Selfiecity begins this work. There are three main areas of analysis on the site: ‘imageplots’, ‘selfiexploratory’ and findings. The imageplots assemble thousands of images to reveal interesting patterns among the data, as well as being fascinating to look at in themselves. The interactive selfiexploratory is a beautifully designed interface that allows users to search the dataset, using variables such as mood, head tilt, gender, age and city. Conclusions can be drawn from both. Some of them confirm the clichés – more women than men take selfies, and younger rather than older people, the dominant mood is upbeat. But some more unexpected findings have emerged: selfies account for only 4 per cent of images tagged on Instagram (cats are more popular); women tilt their heads at an angle 50 per cent greater than men; women in Sao Paulo tilt their heads an average of 17 degrees, compared with an average of 11.15 degrees across the other four cities.

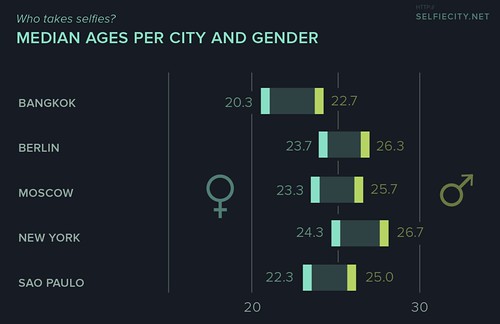

Chart mapping who takes selfies using the median ages per city for both genders – for women, 22.8 and for men, 25.3.

The website includes essays by critics – for example, the media theorist Elizabeth Losh, who expresses concern that the binary terms ‘female’ and ‘male’ are exclusionary. (These strict criteria are an issue with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk – an online marketplace for workers who will accept low rates of pay for completing simple ‘Human Intelligence Tasks’ – the means which made Selfiecity’s mass data-analysis possible.)

Still, tools for analysing this type and quantity of data are in their infancy, and Selfiecity at least suggests some lessons about one aspect of contemporary image culture.

Photomontage of more than 4500 selfies.

The other half of the equation is how and why we use networked images. To use John Berger’s phrase from Ways of Seeing, we have ‘moved toward Democracy then stopped’. Envy is a common emotion. Some have status and things; others don’t. Glamour becomes a substitute for change. ‘Having’ obliterates ‘being’. The status of being ‘seen’ becomes all.

But in theory the Selfie offers all of us – not just the rich and famous – a chance to be seen. Just suppose that the focus of social media were less on individual narcissism, self-promotion and envy, and more on the many invisible, elusive problems we face as a society? How might we give shape and form to those issues? The systems of visual analysis being developed for projects like Selfiecity could become part of the answer.

Selfiecity project team: Dr. Lev Manovich, Moritz Stefaner, Dr. Mehrdad Yazdani, Dr. Dominikus Baur, Jay Chow, Daniel Goddemeyer, Alise Tifentale and Nadav Hochman.

Noel Douglas, artist, designer, educator, University of Bedfordshire

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.