Monday, 8:00am

15 May 2023

Type for survival

How

type design is helping to save Indigenous Canadian languages from

extinction.

Will Novosedlik reports

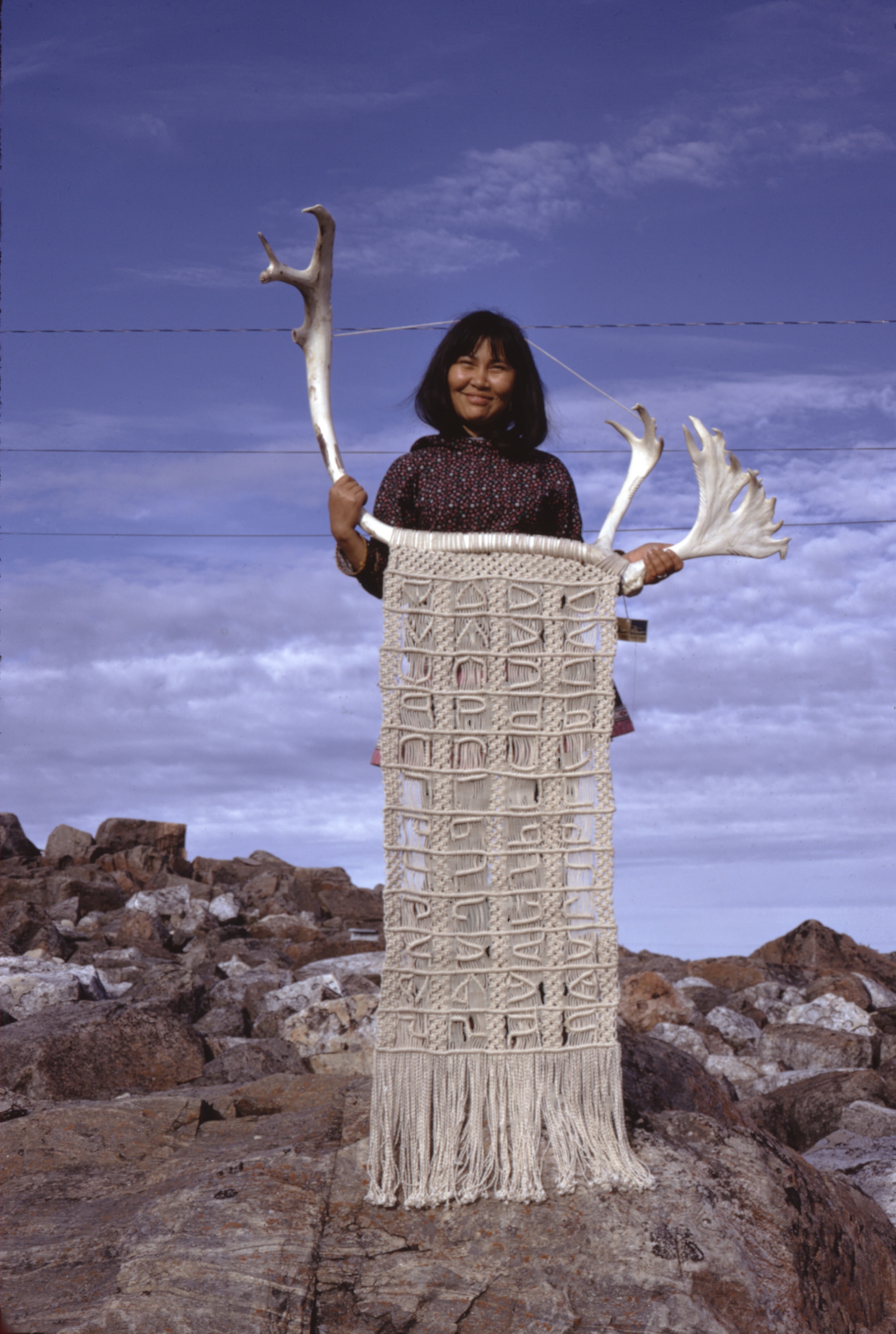

A traditional Syllabics macrame created by members of the Nattilik community in Western Nunavut. Photo by Judy McGrath, 1977.

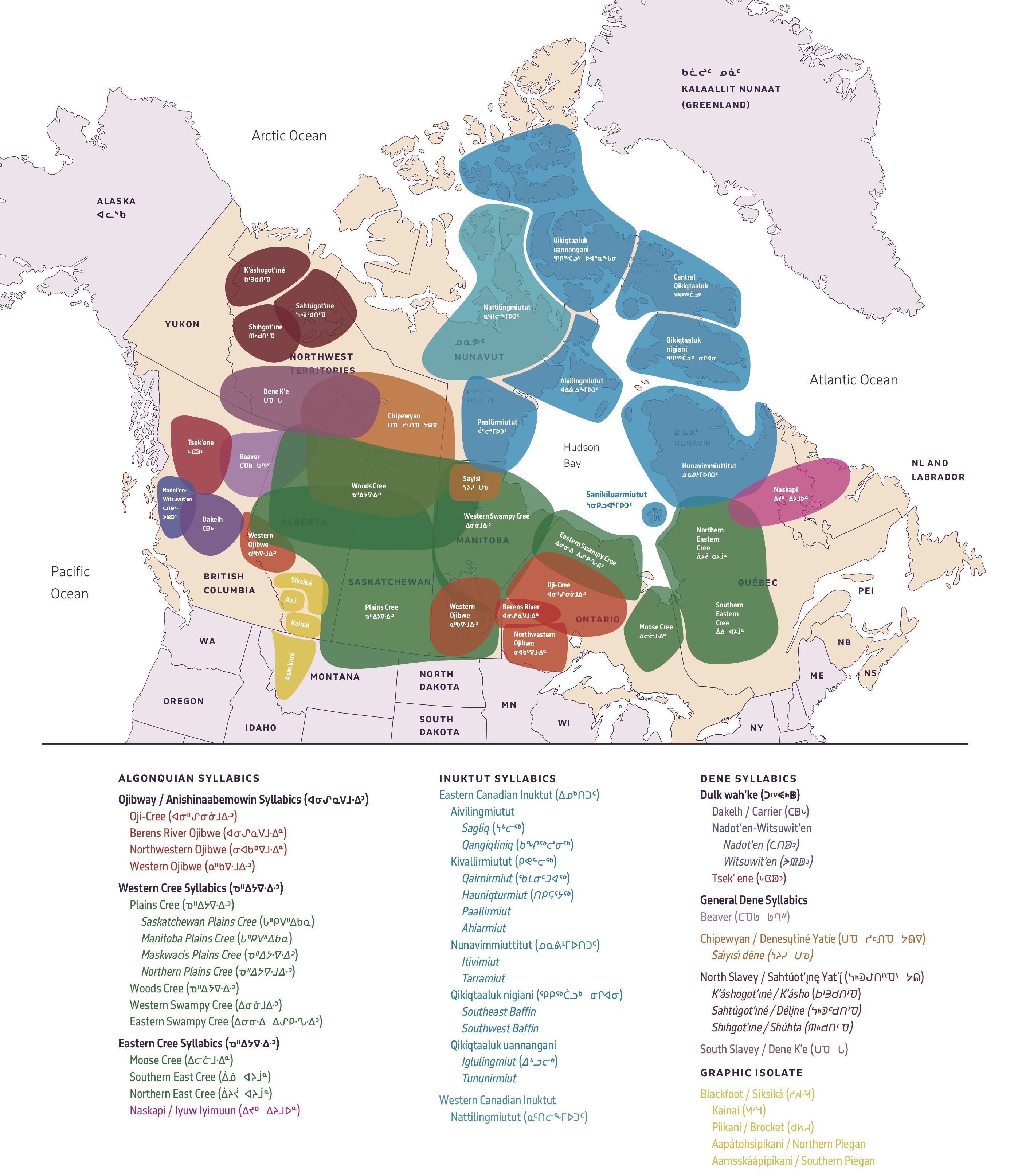

Map by Kevin King of the geographic distribution of the Indigenous languages that use the UCAS across North America, broken into dialects and regions. Some of these primary languages – such as Nêhiyawewin, Anishishinaabemowin, Siksiká and Inuktut – have linguistic communities outside Canada – in the United States, Siberia, and Greenland.

English-speaking designers take it for granted that no matter what typeface they want to use, it will be available in their language, and it will work on any device, writes Will Novosedlik. It is after all the world’s most spoken language, due to its legacy of conquest and its historical association with the thrust of global capitalism. As a result of its linguistic hegemony and its monopoly on commerce, types tend to be created for English first.

Peter Biľak, founder of Netherlands-based type foundry Typotheque (see Eye 75), learned this the hard way. Biľak was born in the former Czechoslovakia. As a student in Bratislava he took an interest in writing and publishing, but unlike most writers, not only did he want to write the book, he wanted to design it too – every part of it.

When it came to selecting a typeface, he hit a wall. The ones he was keen on were not designed for Czech or Slovak. Czech and Slovak make heavy use of diacritics, none of which are used in English. The few Soviet-era Czech and Slovak typefaces he did find were not that well designed. He started hacking American and Dutch types by trying to add diacritics to them, but found that their high x-heights made for a very awkward fit.

As Biľak explains, ‘It occurred to me that how language looks has to do with how language works, but most type designers do not think about what that means to a language like Slovak. It would never have occurred to them that it needs to be proportioned differently than English.’

Between 2005 and 2007 Bi’lak was involved in the research project Typographic Matchmaking initiated by the Khatt Foundation, which paired him with Lebanese designer Tarek Atrissi to design a typeface that worked in both Latin and Arabic. Progress was slow and the obstacles were many, but eventually they created Fedra Arabic, a typeface that became very popular across the Middle East. Biľak realised that he did not need to be a native speaker of all languages to design types for them.

Two years later he opened a type foundry in India – possibly the first one on the subcontinent to create fonts for Indic languages that work across platforms and different applications. Research revealed that somewhere between 400 and 700 languages are spoken there, depending on how you distinguish a language from a dialect. Most are local, and many of them lack proper typefaces. At the same time, the Indian government, in a nationalistic bid to create the illusion of a unified, homogeneous India, has been pushing hard to make Hindi the official national language, even though it is spoken by only 30 per cent of the population. This puts all those local languages at risk of extinction.

This is not just an Indian issue. According to Biľak, ‘In the world right now, there are about 7000 languages spoken. Half of them are purely oral. Half of them risk not being passed on to new generations and will likely disappear by the end of the century. Some say the figure is more like 90 per cent. It is not unlike the loss of biodiversity: it may have taken millennia to develop, but once it has gone, it’s gone for good. All the knowledge available only in those languages will be lost.’

Among those languages on the edge of extinction are the ancestral tongues spoken for more than 10,000 years by the Indigenous peoples of Canada. The arrival of European colonisers in the sixteenth century marked the beginning of 400 years of cultural genocide. A big part of that dark history is that generations of Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their families at a tender age to attend government and church-run schools, where their language and culture were beaten out of them. As has been recently discovered, thousands of them never came home, ending up instead in unmarked graves due to physical and mental abuse, poor hygiene and severe malnutrition. These schools were little more than concentration camps.

Between the 1870s and 1990s more than 150,000 Indigenous children across Canada attended what came to be called The Residential Schools as part of a government effort to ‘assimilate’ Indigenous people into settler culture, a process first outlined in a report commissioned by Governor General Sir Charles Bagot in 1842 The report recommended that ‘the children be sent to boarding schools away from the influence of their communities and culture, (and) that the Indians (sic) be encouraged to assume the European concept of free enterprise.’

Kent Monkman, The Scream, 2017. Acrylic on canvas, 84" × 126". Collection of the Denver Art Museum. Image courtesy of the artist.

[1] Joseph, Bob, 21 Things You May Not Know About The Indian Act, 2018.

[2] Statistics Canada, The Aboriginal Languages of First Nations people, Metis and Inuit, 2016.

On arrival children were forbidden to speak their own language and were severely punished if they did. They were made to feel inferior and ashamed of who they were. Consequently, when they were allowed to return home for visits they often felt ashamed and afraid to speak their own language, even with their families. And when they grew up, they taught their own children English and avoided transmitting their Native language so that their kids would not suffer the same punishment when they were taken away to the Residential Schools. As a result the use of Indigenous languages declined, just as the Bagot report had hoped it would. In 1996, UNESCO declared that Canada’s Aboriginal languages were among the most endangered in the world [1]. By 2016, only one in six Canadian Indigenous people was able to speak an Indigenous language [2].

‘Survival of a language is survival of a way of being in the world and with each other – it is irreplaceable.’ These are the words of Janet Tamalik, PhD, an interpreter and keeper of Inuit languages.

Tamalik is of European origin, but spent part of her early life with her family in Nunavut, where she became fluent in Nattilingmiutut, a local dialect of the Inuktut language. While in high school, her fluency got her a job as an interpreter for Inuit members of the legislative assembly. Over time she was very concerned to see how few of the next generation were learning Nattilingmiutut so she dedicated her life to curriculum development, advocacy and revitalisation.

[3] The term ‘syllabary’ refers to the fact that the characters represent sounds made by the combination of a consonant and a vowel, whereas in Latin alphabets each character represents the sound made by a single vowel or consonant.

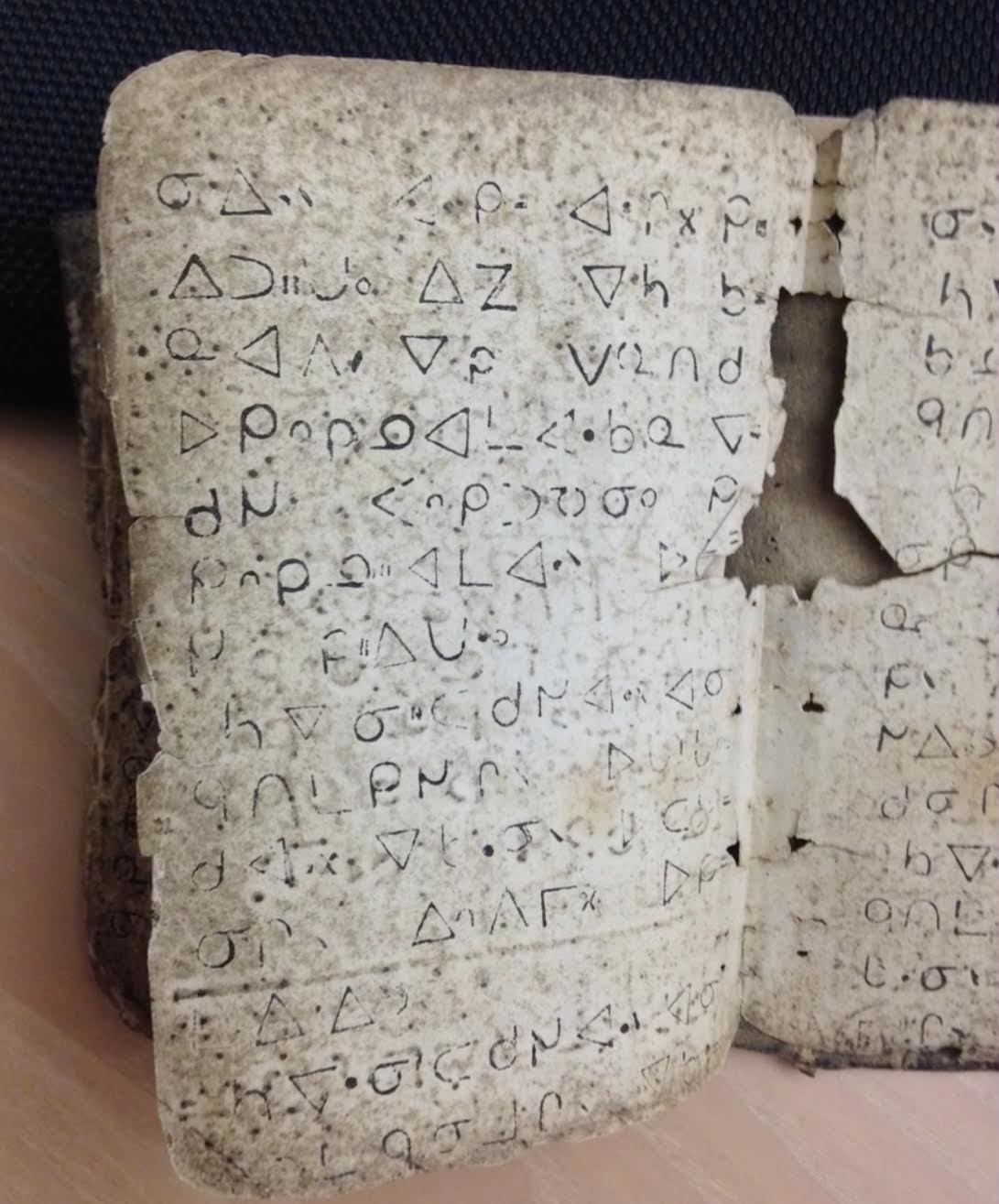

For many thousands of years, Inuktut existed only in oral form. In the mid-nineteenth century an Inuktut syllabary was adapted from a Cree syllabary that was developed around 1840 [3]. In 1976, The Inuit Cultural Institute (ICI) standardised the syllabary, but somehow missed a total of nineteen sounds unique to the Nattilingmiutut dialect. According to Tamalik, Nattilik language keepers created new symbols for these missing sounds and a custom font and keyboard were developed. But the symbols did not work across operating systems or on any device that did not have the fonts and custom keyboard installed. As a result, they could not be reliably used in email or other digital text that was to be shared.

The reason for this was that up until 2020, twelve of the Nattilik Syllabics were not included in the Unicode Standard – the universal digital text encoding standard which assigns a unique number to every character in any language, allowing it to be recognised and rendered accurately across platforms, devices and applications. Despite several attempts over the years to get them included, Tamalik and her community got nowhere.

Macrame sculpture of Nattilik syllabics, created by Arnaoyok Alookee. Photo by Judy McGrath.

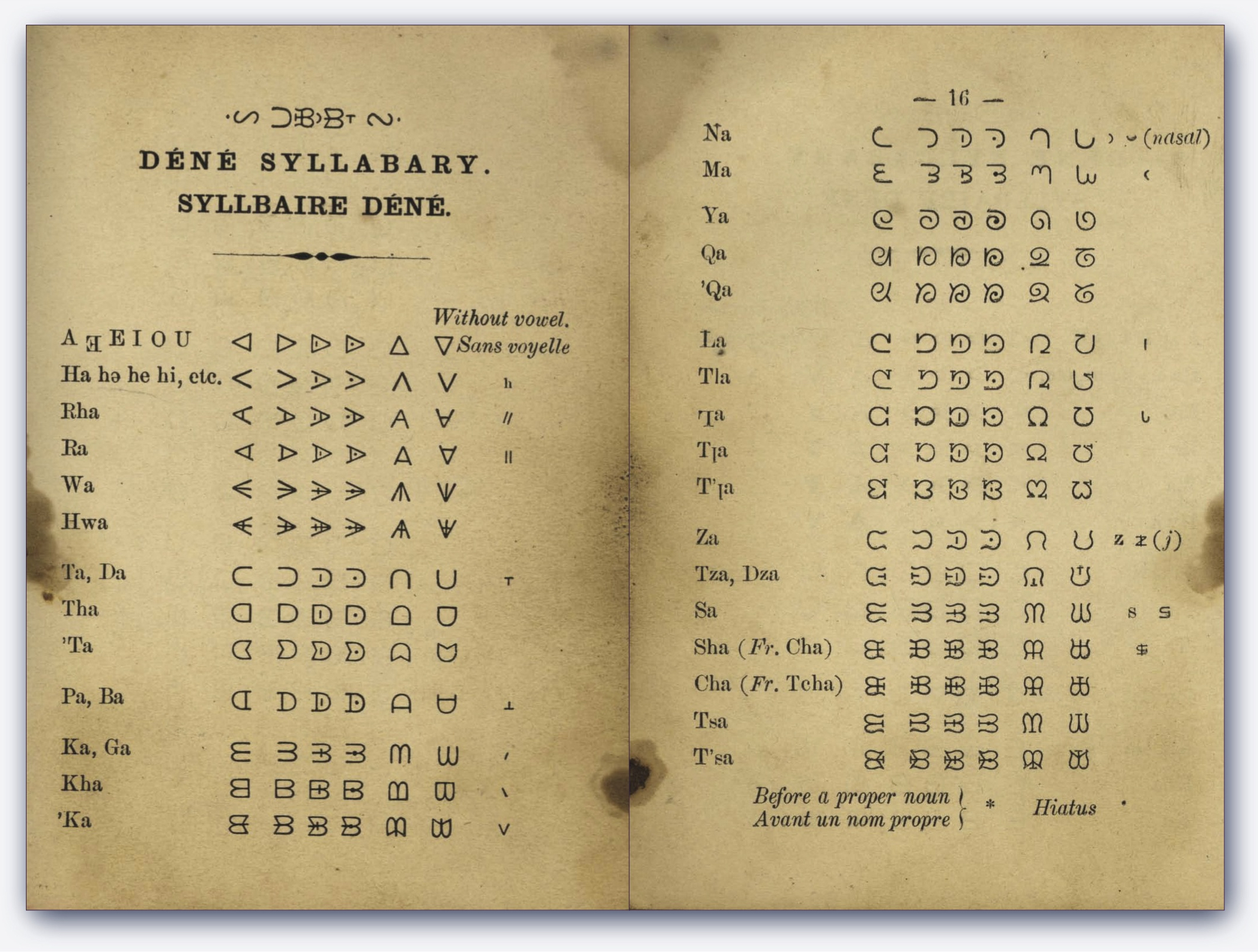

The Dakelh (Carrier) Syllabics, from Adrien-Gabriel Morice’s Carrier prayer book, 1901. The first printed syllabics appeared in 1841 for the Cree First Nations and were adapted for use by many other Indigenous communities, including Inuktut, Anishinaabemowin, and Dene language communities.

Then

in 2020, Tamalik received an email from Kevin King. The Toronto-based

type designer had partnered with Peter Biľak as Typotheque’s

representative in Canada, with the express purpose of designing

typefaces for Indigenous language preservation and revitalisation.

While in search of Indigenous communities who might be interested, he

contacted Tamalik. As Tamalik tells it on her website, ‘Kevin said

he was interested in supporting Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics users

to have more graphically beautiful fonts for their productions. He

had noted in his research that there were some symbols that were not

in the Unicode Standard. Before creating any new fonts, he had

proactively petitioned the Unicode Consortium for the inclusion of

various missing symbols, including

Nattilik

ones! I asked him how on earth he knew about the missing

characters. The community’s push for inclusion never found any

traction over the decade of trying to get assistance. He said it was

from an article he had read in the Nunatsiaq News. I began linking

him with all the others in the Nattilik area who wanted their symbols

included into the Unicode Standard. We all worked out the finer

details together, writing supporting letters and providing examples,

updating each other, conveying questions and answers across time

zones and spaces.’

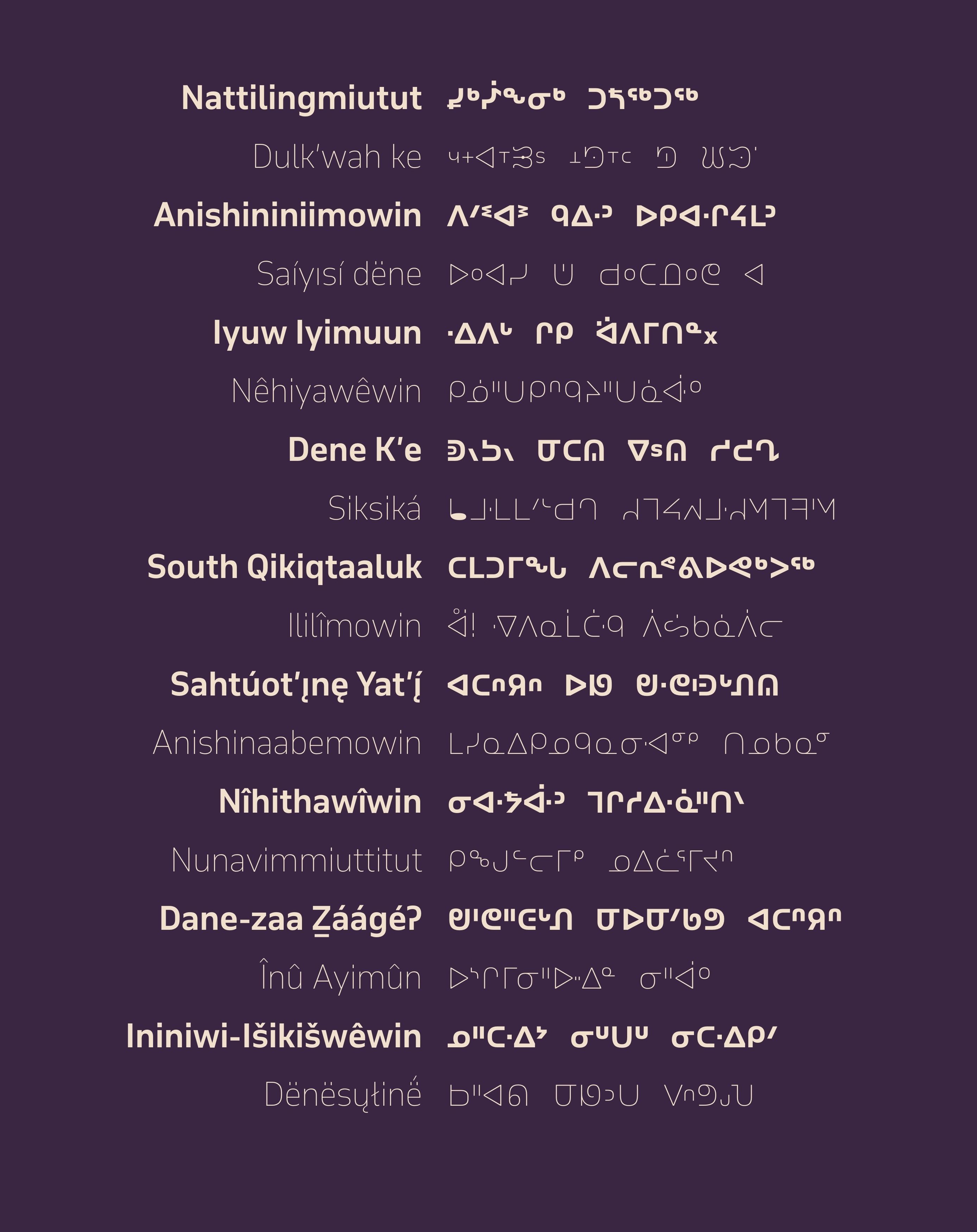

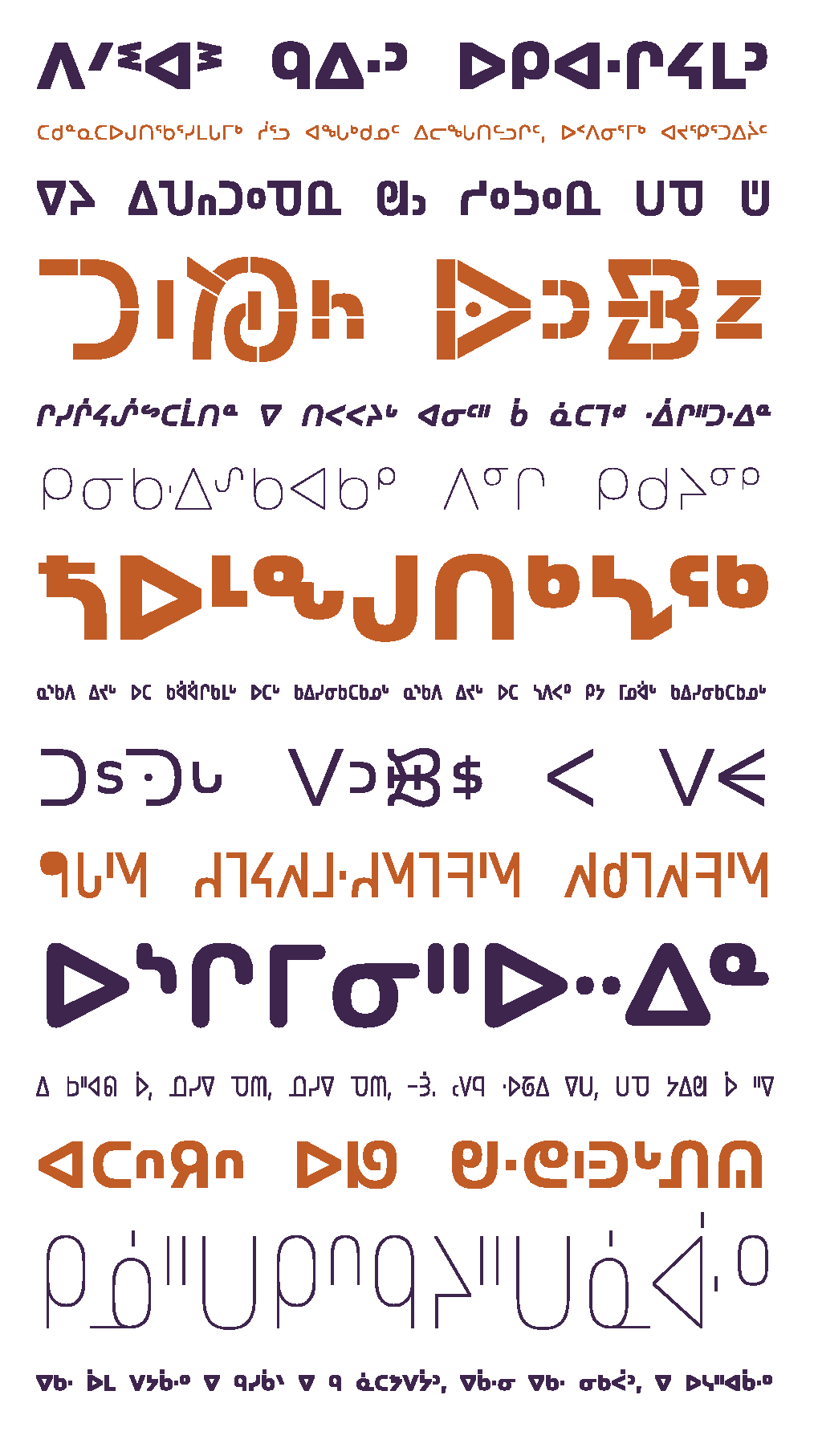

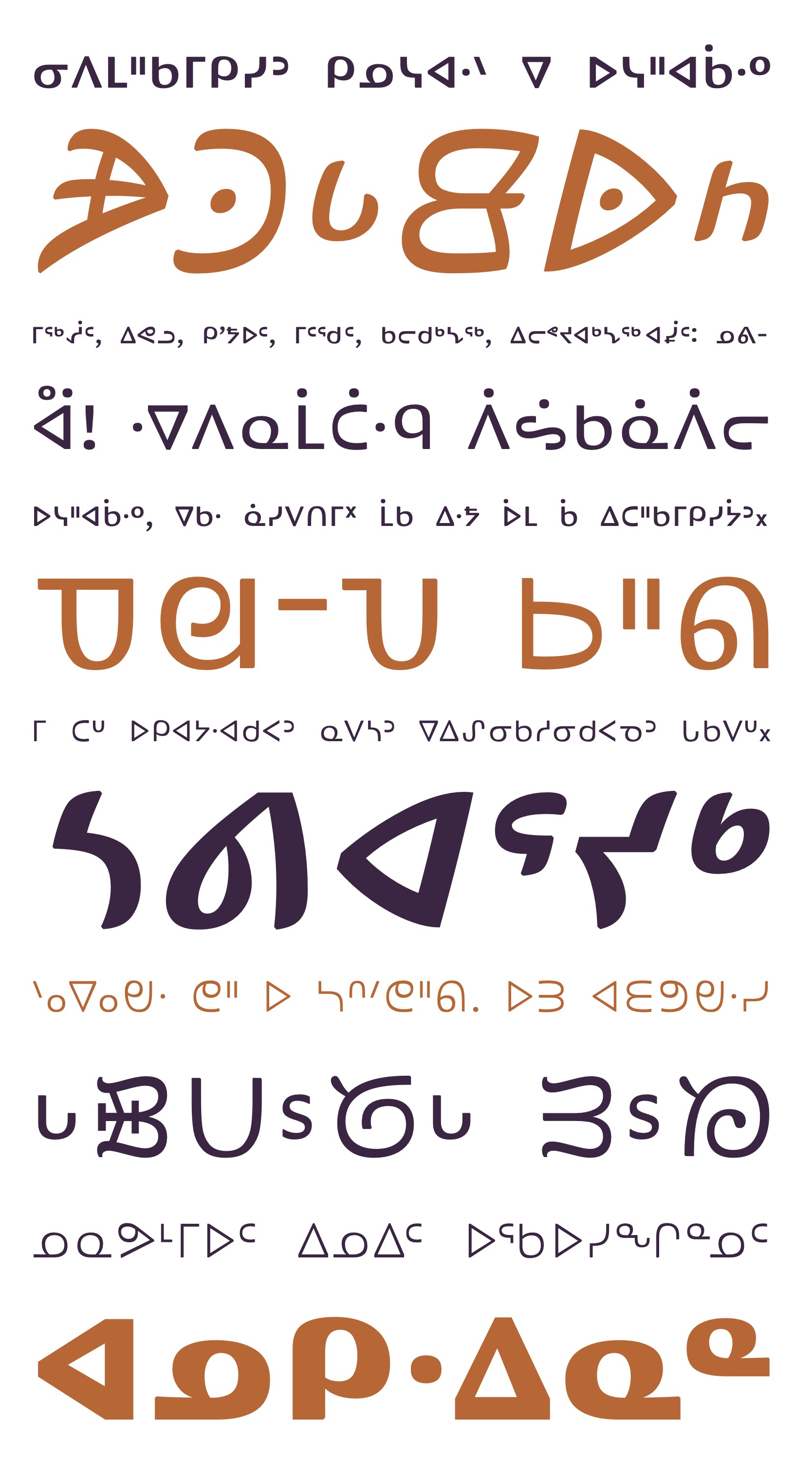

Sample settings of Typotheque’s November syllabics showing

similarities and differences across eighteen of Canada’s Indigenous

language communities.

Tamalik continues: ‘The Nattilik missing symbols were officially approved by the Unicode Consortium for inclusion into the Unicode Standard system in early October 2020.’ Tamalik goes on to say that Kevin is working with her and her fellow language keepers to ensure that there are also pre-installed keyboards in major operating systems such as Apple, Google and Microsoft.

Opening frame of a video about the project made by Typotheque. It sets the context for this project and affords us a glimpse into life in the Arctic and the challenges of language preservation.

This co-creative way of working, wherein the designer takes on more of a facilitative, collaborative role – rather than assuming the posture of the ‘creative hero’ – is typical of Typotheque’s approach. While Tamalik gives most of the credit to the elders and teachers she worked with for their persistence and hard work in achieving this initiative, she also highlights the fact that having Typotheque’s help meant being heard, valued, and understood. Rather than impose a solution, King took pains to listen to the language keepers’ needs. This is exactly the opposite of how settlers have historically treated Indigenous communities.

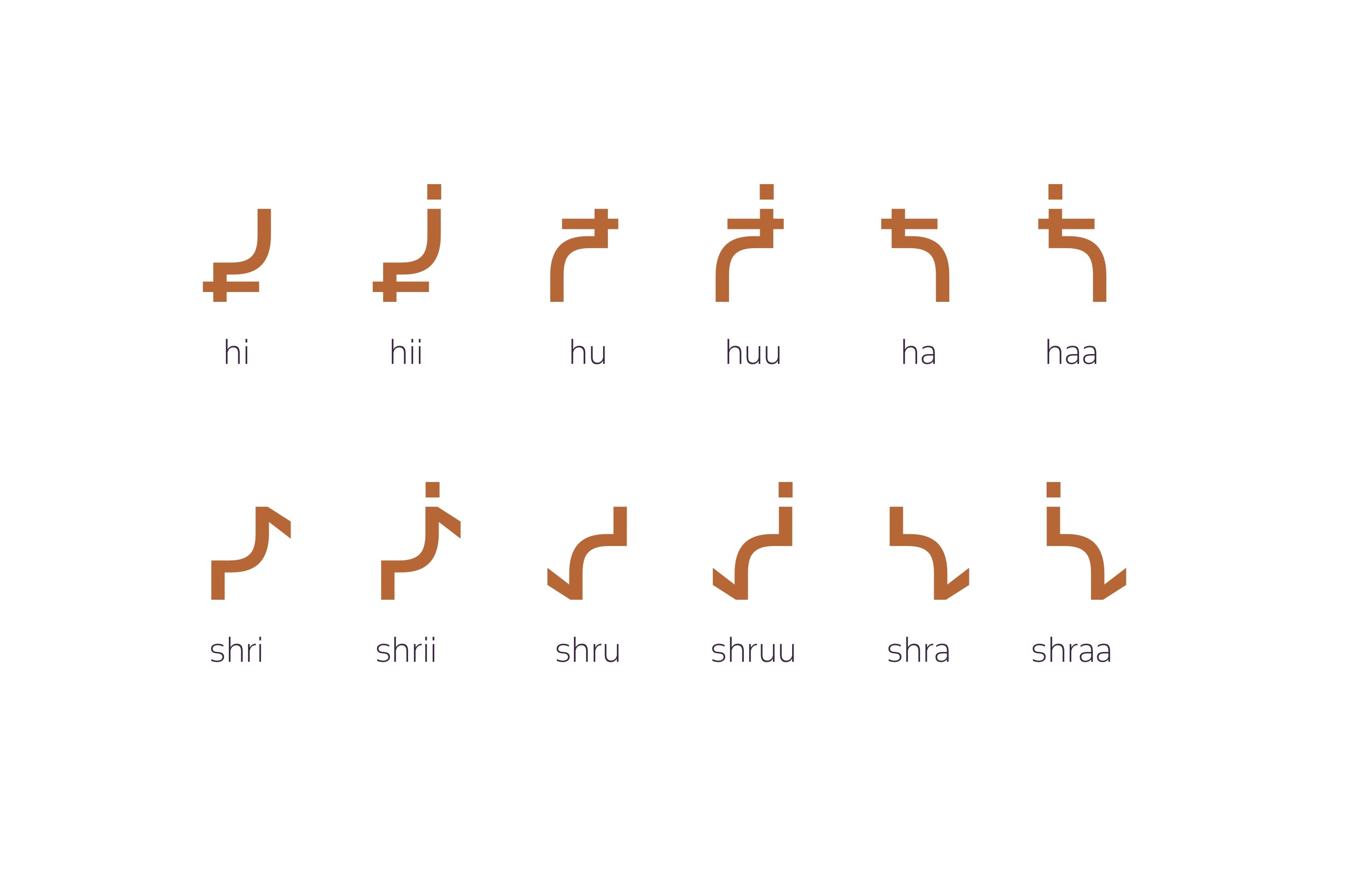

The twelve missing characters that Nattilik language keepers identified for encoding were required for

rendering unique sounds in the Nattilik language (Nattilingmiutut) in Western Nunavut, a member of the

Western Canadian Inuktut language family.

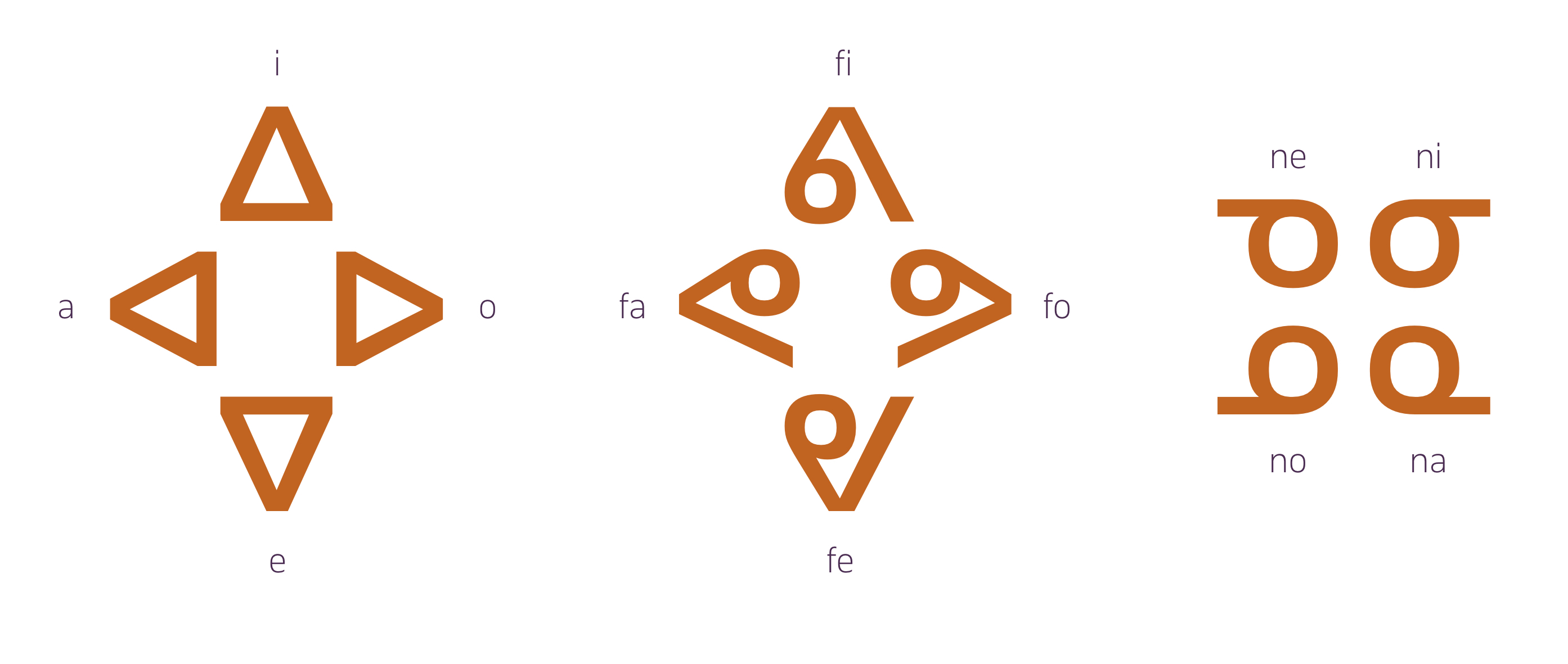

One of the key characteristics of the syllabics system is that by rotating the same character through 90 degrees a different vowel sound is represented for each syllable.

Left. the four vowel sounds used in UCAS.

Middle and right. Two

of the syllabic series showing how the rotation pattern is repeated for each syllabic character.

November Syllabics across various different Canadian Indigenous languages. This is a low-contrast typeface family containing extensive weight and width members. Informed by community research and user testing, November expands the typographic palette of the Syllabics while offering comprehensive coverage of the local typographic preferences for all Indigenous communities in North America that use the script.

Lava Syllabics. A contrast Syllabics typeface family with a secondary style for adding layers of expression. In addition to providing localised Syllabics community support resulting from the comprehensive research findings in the Typotheque North American project, Lava Syllabics expands the typographic palette to offer additional devices for expression and organisation in typographic layouts.

This more empathetic posture is a reflection of Typotheque’s way of doing business. Much of its work is self-initiated, community-focused and concerned with social impact. That is not to say it is not commercially viable. But it does mean that the business model is different and the financial return is slower. Over time, the model has proven itself to be self-sustaining. Says Biľak, ‘The cycles may be long, but the revenue streams of projects that we initiated ten or fifteen years ago pay for projects that are being initiated now.’

When asked to reflect on the forces that continue to challenge the preservation and revitalisation of her language for future generations, Tamalik puts English at the top of the list. ‘English is clearly the language of commerce, education and entertainment. That has a lot of power in a child’s mind. However Inuktut is the language of the heart, the land and the people. And if children have enough role models and experiences in Inuktut, they can grow up perfectly bilingual, and pass that on to their children.’

[4] The Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics for Cree, Inuktut and Ojibwe, The Atlas of Endangered Alphabets.

According to a website called Atlas of Endangered Alphabets, a study by Statistics Canada found that Aboriginal children who speak an Aboriginal language are more likely to look forward to going to school, and once at school they show stronger verbal skills (in expression, mutual understanding, storytelling and overcoming speech and language difficulties) and are also more likely to display what is called prosocial behaviour (that is, kindness, politeness, willingness to help with or empathise with others) and less likely to suffer from hyperactivity and inattention [4].

Tamalik reminds us that without a precise phonetic system that is compatible across platforms, her language would simply not survive. ‘The work supported by Typotheque is a huge step … I think we will look back in a decade and see how much was made possible by these first steps.’

Her hopes are echoed by Francois Prince, a language keeper from the Carrier Nation in British Columbia with whom Kevin King has been working on a similar project. ‘The language is about connection. It is connected to everything: your body, the land, the community. People feel ashamed to not know their language. The syllabics will heal our people and heal our wounds.’

Syllabics typewriter. A Remington typewriter outfitted for preparing texts in both Cree and Dene Syllabics, manufactured in the 1940s. Syllabics typewriters replaced lead type printing methods in the early twentieth century, and increased accessibility to more Indigenous communities towards preparing more formal texts for reproduction. Photo courtesy of Sam Waller Museum, 2021.

Swampy Cree Hymn book, printed by James Evans at Norway House, Manitoba, 1841. This is the earliest known printing of the Syllabics for any language, representing a typographic manifestation of the writing system. This document served as a model for the adaptation and development of Syllabics orthographies for other Indigenous communities across northern North America. Image courtesy of the James Evans Fonds, University of Victoria library, University of Toronto, 2018.

Will Novosedlik, graphic designer, Toronto

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.

Links

Kent Monkman website

Kevin King: ‘Syllabics typographic guidelines and local typographic preferences’

Kevin King: ‘On developing a secondary style for the Canadian Syllabics’

Kevin King’s site

Unicode: ‘Working with Local Communities to Revitalize and Preserve Indigenous Languages in Canada’

More articles by Will Novosedlik on the Eye site

The Syllabics Project – video made by Typotheque