Spring 2023

Jump cuts

Len Lye

Fraser Muggeridge

Saskia Marka

Roy Terhorst

Hiromu Oka

Droga5

Oliver Latta

Extraweg

Mitch Paone

Dirk Koy

Motion design is everywhere. The gleaming screens of our phones, TVs and poster sites demand more and more ways to make words and pictures dance in space and time. By John L. Walters

There is nothing new about moving type and image. The desire to make graphics move, to see type twist and change within three-dimensional space – or create that illusion – has been around for some time. The optical effects of signpainting, day-glo inks, shadows, embossing and debossing all allow the designer to play with the idea of kineticism, even when there is no actual movement. The need to animate graphics for film, TV, advertising and branding has provided the economic driver; the human desire for novelty, in tandem with all that technology permits, has provided the impetus.

Here in the third decade of the 21st century, motion design is everywhere. The tablets in our hands, like the enormous screens that fill entire billboard sites, are static objects on whose gleaming surfaces we perceive the fantasy of graphic outlines that swell, burst, swivel and change constantly in a 2D simulacrum of 3D space and time. What’s new is the ubiquity and diversity of means to make words and pictures dance; the multiplicity of ways to display the results; and the number of practitioners working in this field. Successive waves of creative activity have become a tsunami.

Motion design can be traced through shadow play, flip books, mechanical displays, optical tricks, kinetoscopes and the discovery of the way ‘persistence of vision’ creates the illusion of movement, which led to the permanent revolution of cinema. Within the history of early film, the work of pioneers and artists including Reiniger, Fischinger, Richter, Ray, Duchamp, Lye, McLaren and Bass have long been of especial interest to graphic designers. Saul Bass’s prolific work, which spanned four decades (from Carmen Jones to Casino), set a new standard. As Joel Karamath argued in Eye 39, Bass was a ‘collaborative auteur’. Innovative work by designers as different as Bernard Lodge (Dr Who), Pablo Ferro (Dr Strangelove) and Dan Perri (Star Wars) showed what could be done, and around the turn of the century the work of Kyle Cooper (see Eye 66) inspired a new, more digitally minded generation.

More recently, long-form TV provided titles designers such as Imaginary Forces (Mad Men) and Patrick Clair (True Detective) with an extended canvas for titles that told a story, set the scene and ‘branded’ a long-running show. The website Art of The Title documents this rich history with hundreds of sequences that go back to the dawn of sound (Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) via classics such as Stephen Frankfurt’s titles for To Kill A Mockingbird to the latest work by Saskia Marka, Prologue, Aaron Becker and Oliver Latta, aka Extraweg.

Is motion design a medium, or a discipline, or just another part of the designer’s expanding toolkit, to be used when needed? Is it a specialism, which needs a different kind of design education? Or a craft, which requires training in the arcane tools of analogue animation as much as the more recent tools of Processing and AfterEffects? Is it just another arrow in the designer’s quiver, when applications such as Zach Lieberman’s Weird Type and Kiel Mutschelknaus’s Space Type Generator (see Eye 100) puts coherent motion typography directly into the hands of everyone – from the neophyte to the hovering art director. As ever, the acceleration of technology has a plethora of consequences, many unintended. Happily, since graphic designers are obliged to keep up with the acceleration of software, they may also be the most appropriate people to push motion design forwards.

An essay to accompany an exhibition of work by pioneering graphic artist Len Lye (1901-80) speculated whether motion could be regarded as a medium. Over a long career, Lye – whose handful of 1930s shorts are now regarded as landmarks of motion design – moved between documentary film, animation, design, poetry and painting; between experimental filmmaking, in which he painstakingly painted or scratched directly on to celluloid, and ambitious kinetic sculptures that created movement within a static gallery. A Colour Box, a three-minute short that Lye made for the British Post Office (GPO) was a seminal work. Lye lived and made work in a world whose kineticism was entirely analogue – as it still is for most of us – despite claims made for the ‘metaverse’. Lye wrote: ‘Studying motion is not an intellectual game. There is not a moment in our waking life or dream life that’s empty of kinetic experience. It is present when our heart beats, when our eardrums resonate, our pulse runs, our breathing inhales and exhales.’

Below: A Colour Box (1935) by Len Lye. Top image: Snippet of Shape Study – Line by Dirk Koy.

Len Lye

‘Motion is not an intellectual game. There is not a moment in life that’s empty of kinetic experience.’

Non-narrative motion design

Mitch Paone, co-founder of DIA, has forthright views about motion design: ‘What’s been interesting in the last ten years, and the reason why our work has opened up some thinking about design, is that the approach of motion became linear – not just being a storyboard that played out over 30 seconds that tells a narrative. For us – because all these things (like Instagram screens) amplified what we could do with graphic design – it’s like: why can’t we just take advantage of the fact that it’s screen-based, that it doesn’t necessarily have to tell you a story?’

A different strand of non-narrative work was presented at the second DEMO festival on 6 October 2022 across more than 5000 OOH (out of home) screens throughout the Netherlands. DEMO was co-founded by Liza Enebeis (see Eye 100), creative director of Studio Dumbar. Thonik’s Roy Terhorst, a contributor to the first DEMO, said to Eye in 2020: ‘At Thonik we always start with a particular concept, and then the form will be born from that. On the other hand I have a strong urge to play with shapes in motion to discover new worlds. It’s a great and fun way to teach yourself new ways of design and keep up with new possibilities to stay relevant. This research and underlying philosophy are later often used in Thonik projects [for clients] such as VPRO, Holland Festival and Fondation Cartier. In most of our current projects we animate our graphics, or even better, the printed poster is simply the still form of an animation.’

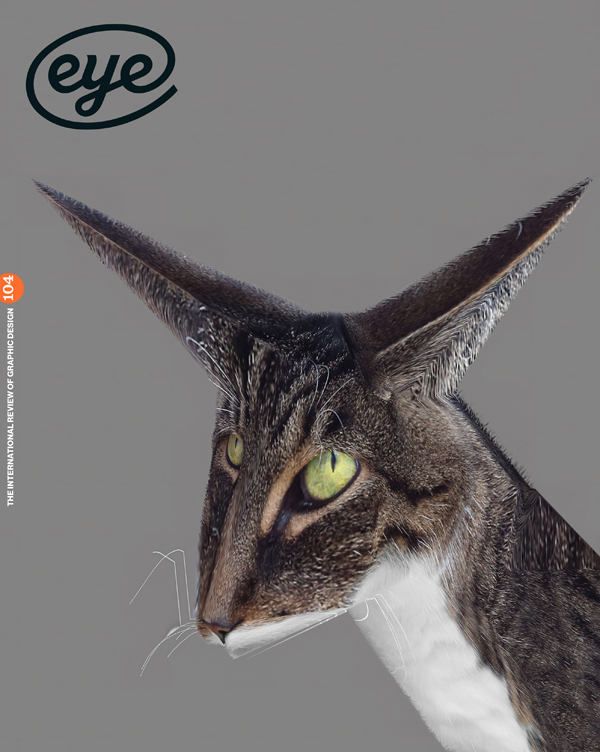

Another DEMO favourite is Dirk Koy, who manipulates real-life footage to create mind-bending images. ‘Koy is always surprising,’ says Enebeis, ‘taking the expected and changing it to the unexpected … bringing motion to something very static.’ In conversation about his practice, Koy explains that he roams the city, filming everyday situations, and heads back to his studio to sift through the material, ‘and see whether something emerges’.

Shape Study 6 by Dirk Koy.

Dirk Koy

‘It was a kind of experiment between control and coincidence, which is still an important part [of] the process in my work today.’

‘I do this on a weekly basis to discover new things for myself,’ says Koy. ‘These are experiments at the interface of the real and digital worlds.’ In his ‘Fixed’ series, Koy manipulates the point of origin of a scene in such a way that the laws of physics appear to change before our eyes. In his ‘Shape Study’ series, he digitally manipulates photos and videos of objects and living beings, to explore ‘how we perceive ordinary places and objects and how they can be represented’. Koy regards the series as a critique of the ‘seemingly endless supply of goods in infinite variation that are available online’. There is a degree of exquisite strangeness in Koy’s work that is hard to imagine in any other medium. ‘I am looking for the painterly component in digital animation,’ says Koy.

A feature of DEMO is that it takes motion design clips way beyond the small scale of a portrait-oriented smartphone, to enormous displays in the physical environment. Untethered from context and sound, these animated posters deliver pure graphics that dance and transform with the abstract abandonment of Lye’s earliest film Tusalava (whose 2022 Tate Modern screening underlined Lye’s contemporary relevance). In interviews, Lye explained that ‘there are three kinds of film technique,’ with a clarity that applies to digital cinema as much as the era of celluloid.

‘One is live action – any kind of object that moves in front of a camera. The second is cartoon, which we all know as “Mickey Mouse”. The third is direct film, which allows you to paint or inscribe or stencil designs directly on the film. I synchronise the action of those visual images with music. Music is abstract sound and my imagery is usually abstract – one enhances the other.’

The present day world of CGI and motion design has many parallels with what Lye called ‘direct film’ or ‘direct animation’, sequences synthesised – effectively ‘inscribed’ – within the digital domain.

Blood on a napkin

Matt Willey is familiar to Eye readers for a wide range of editorial design projects, including Port and INQUE, and he has been a Pentagram partner since 2020. His earliest venture into motion design, the titles for Killing Eve (2018-22), attracted worldwide acclaim. Willey explains that he is only doing title sequences because television producer Sally Woodward Gentle, of Sid Gentle Films, contacted him on the recommendation of designer Ben Stott. While attending the 2018 AGI Congress in Paris, Willey received a phone call out of the blue. ‘She emailed me the Killing Eve script and I sat in a cafe drinking endless espressos. First thing I drew – after reading the scripts – was a pointy “V” and a blood drip on a napkin.’

Killing Eve, season 3 (2022) by Matt Willey.

Matt Willey

‘Light gets turned into graphic dots – I thought this might be a nice way of capturing that feeling without being too literal or cheesy.’

Saskia Marka’s award-winning titles include Babylon Berlin, Deutschland 83, 86 and 89 and The Queen’s Gambit, in which her grainy abstracted square patterns and neat, label-like typography avoided chess clichés with ease. The blue-black monochrome animation synchronises airily with Carlos Rafael Rivera’s symphonic score. Many of her titles are for period dramas, yet the work has a timeless feel, with a distinctive texture that seems highly personal to Marka, and always meshes well with the soundtrack.

Deutschland 86 (2018) by Saskia Marka.

Saskia Marka

‘It looks now like it was always the concept, but it was created from a necessity.’

Oliver Latta’s disturbingly visceral approach to motion graphics, evidenced in his title design for Apple TV show Severance, has brought him wide acclaim. He regards his videos as ‘social observation, playing with everyday situations’. Like Marka, Latta lives and works in Berlin; like Koy, he balances commercial assignments with fine art projects – his pink, endlessly looping NFT Step Into the New Matter was recently on sale at Sotheby’s in Paris as part of a collection of digital works entitled ‘Natively Digital: Oddly Satisfying’.

Hiromu Oka’s animated titles for Hodo Station (a Japanese news programme on TV Asahi) made use of Riso’s personal card printer Print Gocco, bringing warmth, texture and a sense of space to the project, a highly original addition to the canon of urgent television news titles.

Hodo Station (2021) by Hiromu Oka.

Hiromu Oka

‘By using Risograph to actually print on paper and then digitally scan it, I was able to create an authentic warmth.’

In the collaboration between agency Droga5, Fraser Muggeridge studio and director Kim Gehrig for The New York Times’ subscription campaign commercial ‘The Truth is Essential: Life Needs Truth’ (2020), the typeset words were taken directly from the paper’s journalistic content. Muggeridge explains that his response to the brief was to find and use the typography of the original text settings (both in the printed paper and online). The dynamic editing and music add a jittery immediacy to the news extracts, skipping between stories, quotes and headlines.

'The Truth is Essential' (2020) by Fraser Muggeridge studio / Droga5.

Fraser Muggeridge studio / Droga5

It’s not a poster

An American now based in France, DIA’s Mitch Paone frequently collaborates with international type foundries – notably Klim, Optimo and Monkey Type. His campaign for Optimo’s release of Antique Legacy (which stretched to enormous posters as well as epic video clips) has an exuberant monumentality, while his work for Kris Sowersby’s Klim foundry is more intimate and obsessive. Paone says that Sowersby encouraged him to try several new methods – with no deadline. In the end, DIA’s animations for Klim’s Söhne typeface made use of analogue methods, using chemicals, evoking the 1930s ‘direct film’ experiments of Lye and Fischinger.

Paone, who worked with Kyle Cooper and others in titles design before setting up DIA with managing partner Meg Donohoe, has a cinematic way of thinking, and finds himself ‘butting heads’ with the concept of a motion design ‘poster’.

‘I have a terminological problem with the idea of using posters in this context. You’re in motion, you should behave like a video camera. You’re in a world that’s limitless and not confined by borders. The poster designer looks at the format, fits the things and it’s very tight.’

For Paone, an animated poster is a window ‘with the work bouncing around in a frame’. He thinks more like a filmmaker: ‘If you just move the camera, you don’t even have to animate anything. All of a sudden you have a whole other dimension that can be applied. It’s not a poster – you’re in a 360-degree universe you can play with. You’ve got to get out of the frame!’

Roblox 'Brand anthem' (2022) by Mitch Paone.

Mitch Paone

The case for motion design to be regarded as cinema has interesting precedents. Director and CalArts film teacher Alexander Mackendrick (The Ladykillers, Sweet Smell of Success) argued that the camera plays the role of the ‘Invisible Imaginary Ubiquitous Winged Witness’, whose function is to show the audience what needs to be seen. In the set of notes published posthumously as On Film-Making (2004), Mackendrick states that the camera is an active participant in the events to be portrayed, the ‘embodiment of the audience’s curiosity’.

Some of his descriptions of the camera as a ‘winged witness’ anticipate the power of computer-generated imagery by decades: ‘It has magical faculties, living in an entirely fictitious and imaginary world, oblivious to real space and time … it can fly in close enough to study the facial expressions of a character who is sitting alone. Or it might fly out to allow the audience an appreciation of the geography of a crowded room.’

And motion design – like graphic design itself – deserves real life spaces in which we can give it our close attention. ‘There is a big difference when you can see a work as a projection or on display in museums or in public spaces,’ says Dirk Koy. ‘The viewer can engage with a work more intensively without distractions.’ As Lye said, life is full of kinetic experience. Motion design is embedded in everyday life.

Severence (2022) by Oliver Latta aka Extraweg.

Oliver Latta aka Extraweg

‘I want to pull the viewers out of their comfort zone and, what is most important, I want to make them feel or think something.’

Experimental Type (2020) by Roy Terhorst.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.