Monday, 12:00pm

10 March 2025

Digging out the roots

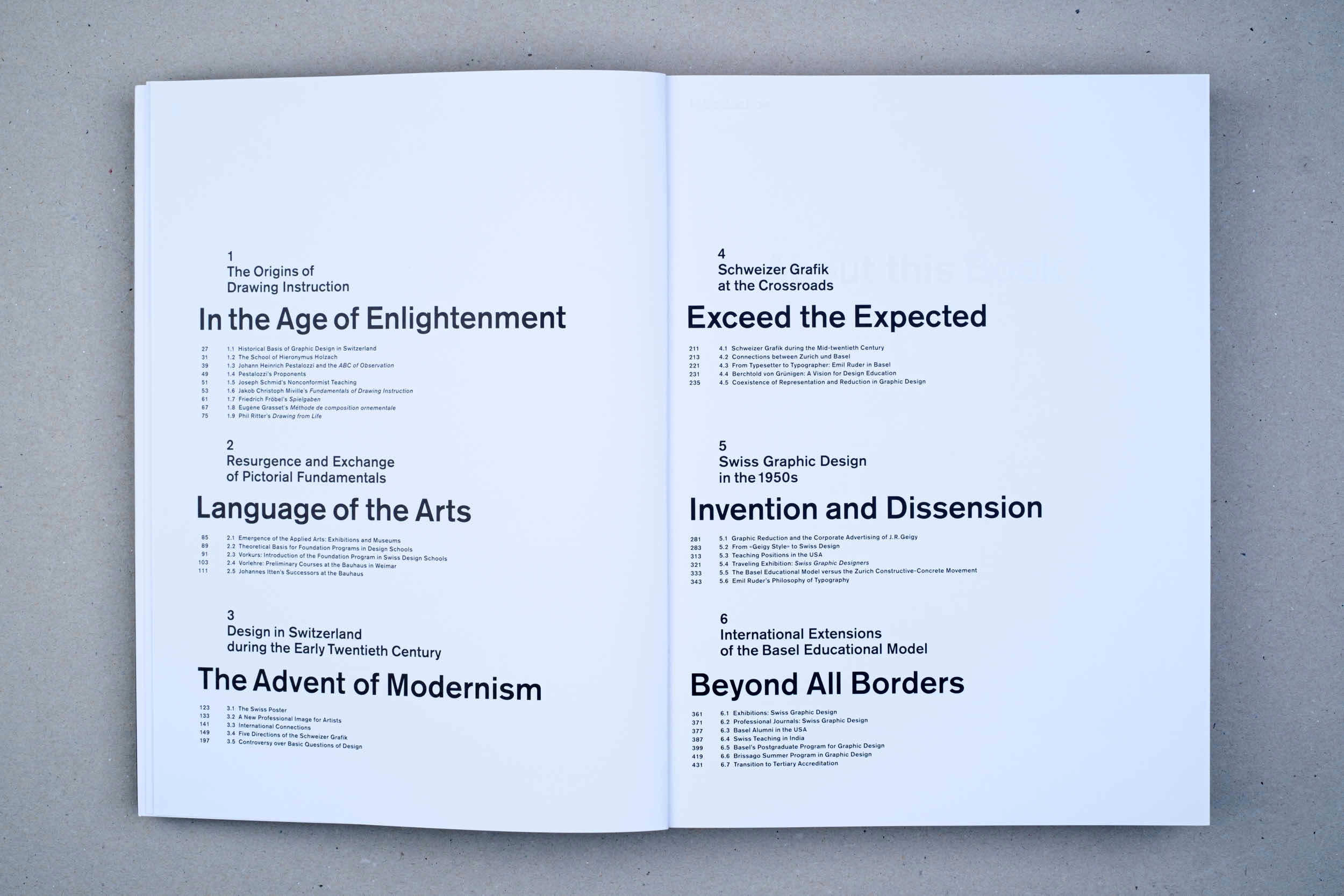

The Birth of a Style: The Influence of the Basel Educational Model on Swiss Graphic Design

By Dorothea Hofmann. Book design: Matthias Hofmann, Lucerne. English edition, Triest Verlag, 2024, €50.40, CHF49, £57.50. Reviewed by Quentin Newark

The Swiss Style is the dominant style in modern graphic design. It is appealing to designers, especially young ones, in its spareness, its limited use of typefaces, its simple techniques like elementary geometric shapes and overlapping colours, its precision. It is so shorn-down, it has little to date it. If you are going to pick a basic approach, then you are safe with Swiss. It always looks cool, writes Quentin Newark.

Several books have tried to get to the bottom of what Swiss Style really is, how it began, who its greatest practitioners are – most notably Richard Hollis’s 2005 book Swiss Graphic Design, (see review in Eye 60) and now we have an English-language version of a book on Swiss Style’s origins that takes us all the way back to the eighteenth century.

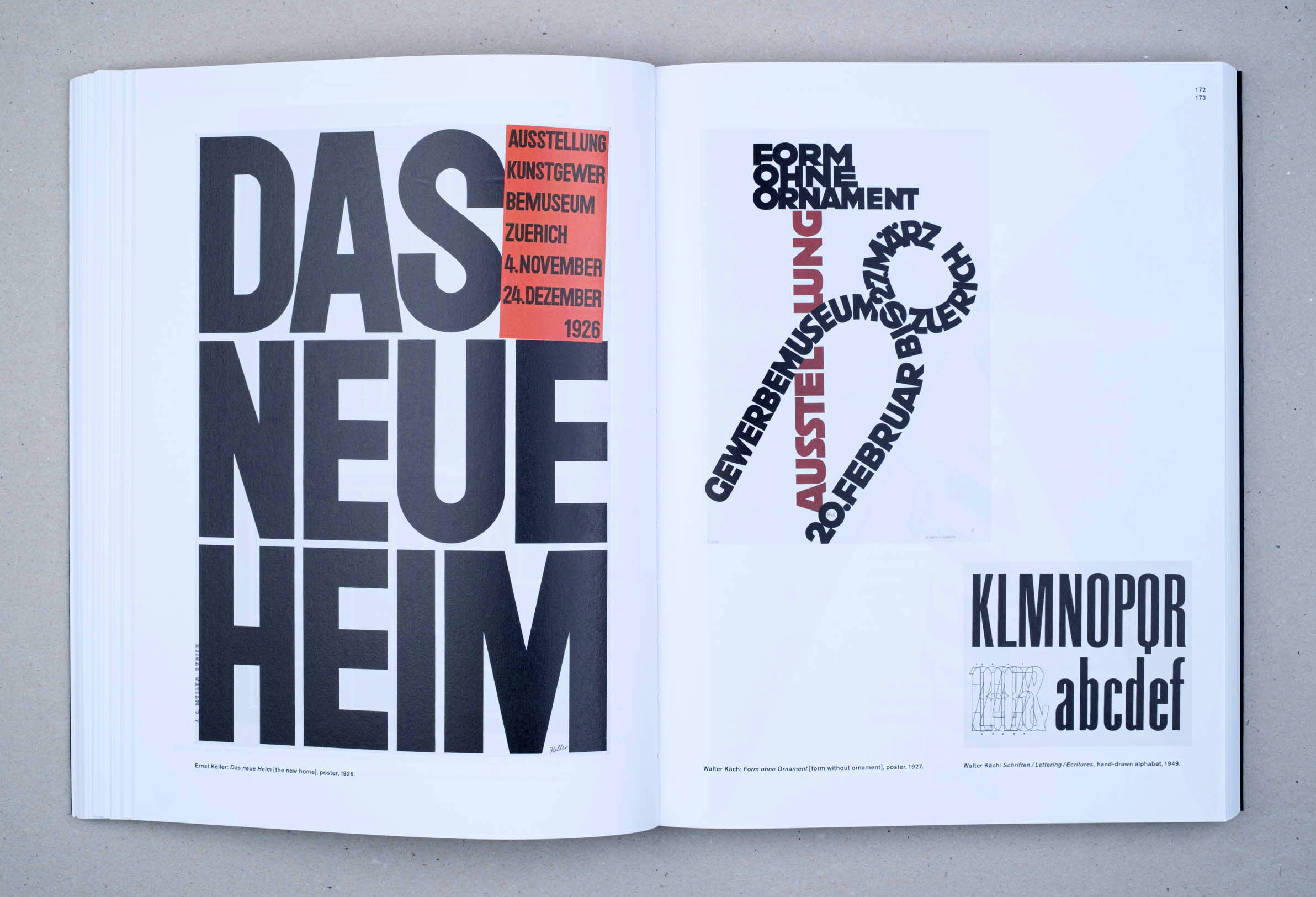

Right. Contents page. Top: Spread from The Birth of a Style featuring posters by Ernst Keller, 1926 and Walter Käch, 1927 and hand-drawn alphabet Schriften / Lettering / Ecritures by Walter Käch, 1949 (see article in Eye 92).

In brief, the author, Dorothea Hofmann wrote a letter to Philip B. Meggs explaining how he had misrepresented ‘Swiss Style’ in his History of Graphic Design, 1983. To substantiate her opinions, Hofmann began doing research that became so voluminous, it turned into this book, first published in German in 2017 (reviewed by Rose Epple in Eye 95).

Much of the book concerns itself with a dialogue between the Zurich and the Basel Schools. This of great interest to an insider, but many outside Switzerland, less alert to its geography and cultural nuances, might be hard pushed to identify the differences.

The book’s great revelation is how far back into Swiss culture Hofmann goes. She tiptoes around the fifteenth century, and the hyper-realistic paintings of Konrad Witz and touches on the construction drawings of Hans Holbein and Albrecht Dürer (who both lived in Basel). But she definitively starts her book in 1762, with the founding of a drawing school by Hieronymus Holzach. She argues, convincingly, that it was meticulous drawing, hours studying how the physical world works, and the systematic teaching method built upon it, that underpins the later Schweitzer Grafik.

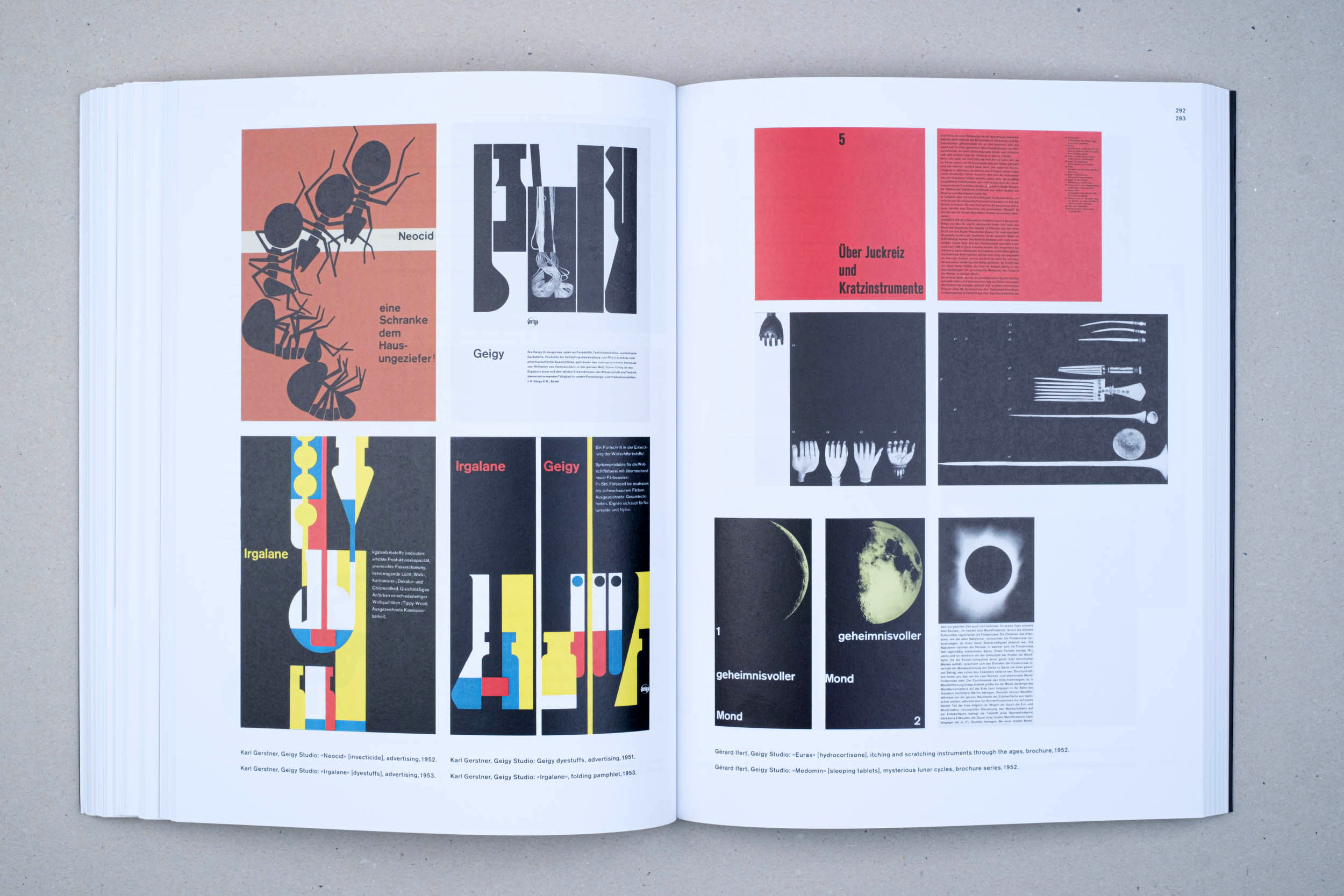

Spread from The Birth of a Style showing advertising work by Karl Gerstner and Gérard Ifert.

Hofmann shows that it was this organised, methodical pedagogy that informed the Bauhaus Vorlehre (Foundation) and all Bauhaus teaching, primarily through the Swiss artist and teacher Johannes Itten, who created the Vorlehre. If this is so, as it would seem to be, then the Swiss approach has shaped all modern design – architecture, furniture, theatre, graphics – far more deeply than was previously understood.

To condense Hofmann’s argument: the discipline of drawing necessitated a study of how things are constructed, in order to depict them accurately. It creates an awareness that surface appearance is created by what underlies it. That approach eventually bears fruit in a graphic design that is inherently industrial, based on how things should be properly constructed, rooted in precision, in minimal means. Hofmann writes: ‘Romanticism and idealisation of nature are superseded by objectivity and pragmatism.’

Should it be rooted in the outer world – the mechanical world, mathematics, the rational – what Hofmann calls ‘plasticity’? Or should graphic design be about the inner world: feelings, whims, dreams and the irrational, self-as-subject?

The book shows us an answer. As Swiss Style graphic design changed, it grew bigger, with ever more people practising it, with new technologies becoming available and more approaches permissible. At the peak of its spare, classical era Josef Müller-Brockmann said: ‘The new typography is the first to try and develop the outward appearance from the function of the text.’ By contrast, Wolfgang Weingart in its later era said, ‘I have tried to put my imagination on paper, perfectly aware that it all may be an illusion.‘ The inner self is a subject worthy of Swiss scrutiny.

Cover.

Quentin Newark, designer, writer, co-founder of Atelier Works, London

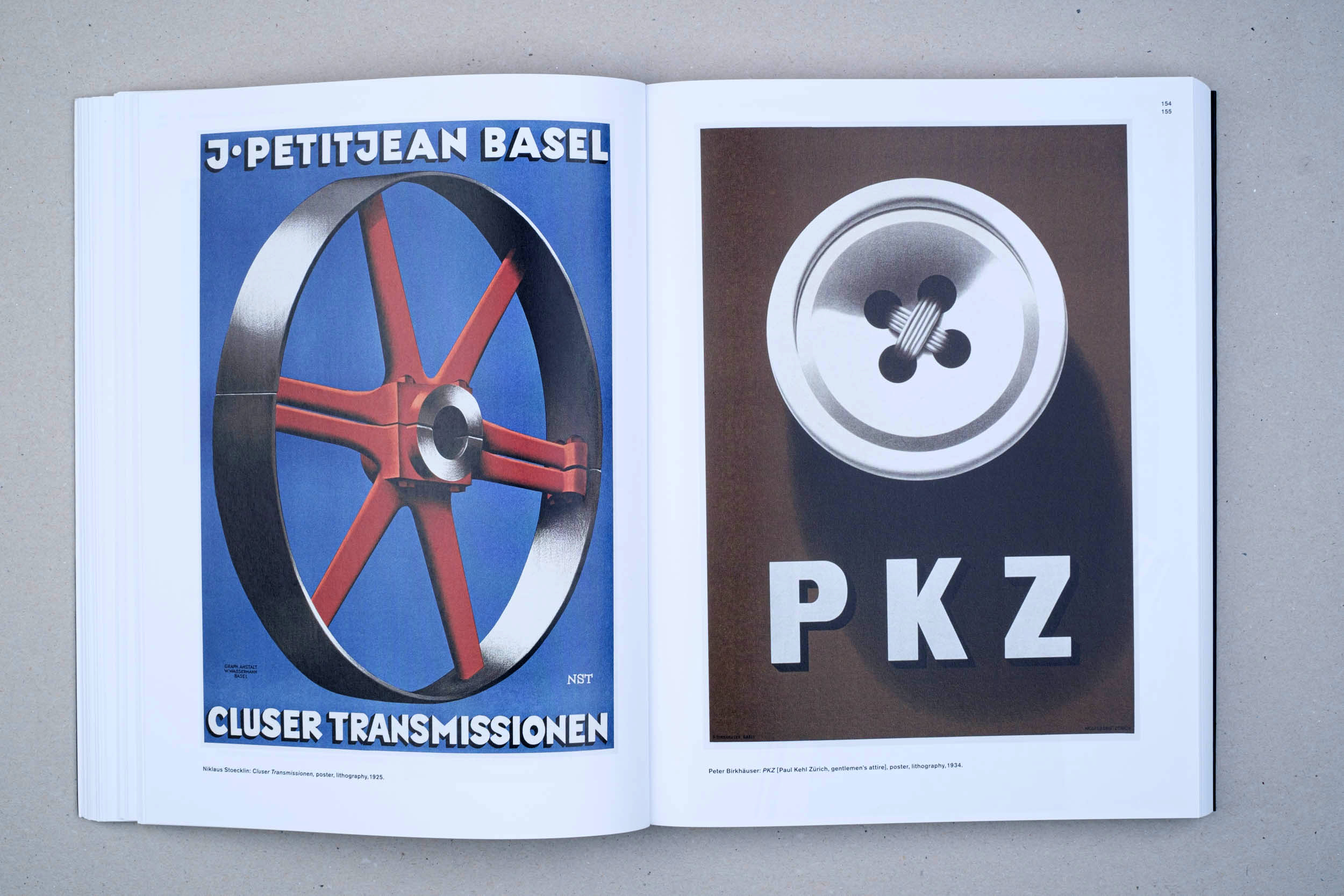

Spreads from The Birth of a Style showing posters by Niklaus Stoecklin, Peter Birkhäuser and Hermann Eidenbenz.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.