Thursday, 1:51pm

7 April 2011

Get real. Go!

Steven McCarthy wonders why US graphic designers don’t get out much

Where are the Americans? Why do international design conferences have such a low turn-out from United States scholars and educators?

Our presence is enormous in other global realms – 50 percent of the world’s defence budget, US corporations larger than many national economies, ubiquitous Hollywood culture, and so on, writes Steven McCarthy.

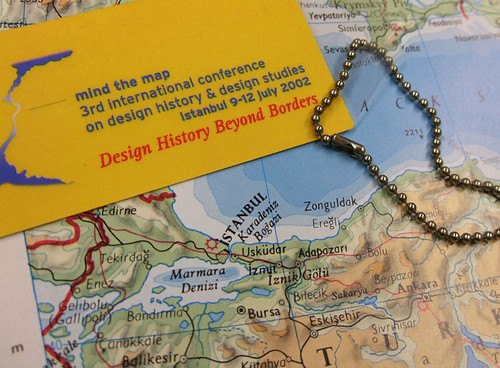

Images: conference name badges and maps from McCarthy’s travels.

According to Professor Sharon Poggenpohl, editor of the journal Visible Language, ‘Organisers of the 2007 conference of the International Association of Societies of Design Research reported that only ten per cent of the paper submissions came from Americans, demonstrating that the US is behind other countries in the generation of new knowledge. 1

This passage was published under the heading ‘Design Research: Building a Culture from Scratch’ on the website of New Contexts / New Practices, an AIGA design educators conference held at North Carolina State University in 2010. Do they mean an ‘American’ culture from scratch, as more mature design research cultures exist elsewhere, and of which many US educators are semi-aware?

I believe that there are two main reasons for this inward-looking approach.

One, the US definition of design research, and its tangible products, often differs from that of other countries’ design scholars, and not in a way that favours many of the US field’s most persistent voices. Still, we have a vibrant and influential design culture, one that deserves a more theorised discourse – beyond the profession’s trade associations, magazines and blogs.

Two, we’ve come to think that the ‘use of both synchronous and asynchronous forms of visual conferencing is central to the experience of global design education. 2 This is a bit like freeze-dried astronaut food – it’s better than nothing, but falls far short of the transformative experience that an actual international exchange can provide. ‘Central to the experience of global design education’ is getting out of one’s pyjamas, logging out of Skype and Google, and crossing the border.

Imagine if our academic institutions defined a learning abroad experience for students as one in which they solely surfed the internet for design sites ending in de, jp, fr, uk, etc.? When the virtual is preferred to the real for the sake of efficiency and ease, immersion is compromised. Haptic and heuristic learning become abstractions, not accomplishments.

Physically being there is required. Besides enriching both the presenter and the audience (generally one’s peers in design education and practice, but also students), attending international conferences and symposia causes Americans to be in the minority. I refer to a national minority of course, but sometimes one of ideology, which provides a healthy dose of global reality. One’s Weltanschauung [worldview] inevitably shifts.

While virtual reality has its place (advantages of cost, convenience, geographic transcendence), it’s no substitute for the sights, smells and tastes, and the challenges, surprises and dislocations, that await us when we literally step out of our comfort zones. This forces us to re-examine our closely held convictions, which is exactly what research does.

Almost all international design conferences are conducted, in whole or in part, in English. If the lectures I’ve given in Belgium, Poland, Portugal and Turkey weren’t in my native tongue, the lingua franca of higher education, I would have been in big trouble! If this doesn’t make it welcoming for North Americans, what else would?

Yes, international travel is expensive, and takes time. If scholars from New Zealand, China, Denmark, South Africa and Brazil show up (with their own limited budgets), why not more Americans? Unlike appearing at a national conference, with fewer time zones to traverse, overseas travel is demanding. I usually arrive a couple days before my presentation to get over jet-lag, and to allow time for exploring. A nice benefit upon returning is the stuff I’ve collected to share with my students: photographs of vernacular signage, printed graphic design samples, a box of uniquely packaged candy, and stories from the frontlines.

Some of these stories have become short essays about my travel experiences that have been published as conference reviews, on Speak Up, on the Eye blog and on the University of Minnesota’s Design Institute’s Knowledge Circuit website. As I hope that my presentations have an impact on the audience, I am transformed by each new venue. Ultimately, scholarship is about sharing.

I would like to return to my assertion about an American definition of design research, which I believe is fraught with internal conflict. I’ve performed over twenty external reviews for faculty tenure and promotion, mostly of American graphic design professors, but a couple of foreign ones too. The recurring entry that persists on many American curricula vita is the notion that having one’s designs published in a commercial magazine’s or professional organisation’s annual competition is comparable to research. (All American designers are ‘award-winning’!) A second is that journalistic writing, while often meritorious in its own right, equals research. Although the result of a highly selective jury on one hand, or the prestige of a notable editor’s invitation on the other, both are flawed definitions. And both get met with quizzically arched eye-brows on the international design research stage.

As most British, Dutch and Australian design educators – in particular – know, one must use a research methodology to do research. Then, one’s findings, or observations, or outcomes (and this certainly includes praxis), must be disseminated through a process of peer review, like (but not exactly like), that used by the sciences and humanities. An expansive definition of design research includes qualitative, quantitative, ethnographic methods, etc. as well as design authorship, ‘critical design,’ speculative and curatorial projects.

Although many non-American design researchers have doctoral degrees, I don’t believe that the PhD is a prerequisite to doing research. I have an MFA, as do many other capable scholars. Furthermore, a growing number of foreign doctorates are in ‘design practice,’ which bridges thinking and making – design as both noun and verb. American design education can only improve by synthesising the propositions of others, and we should reciprocate with our own successes.

International design conferences are a terrific opportunity for sharing, learning and growing as a discipline. They can also be polemical, and perhaps they should be. I often start my presentations with a couple images of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, where I’m from, to provide a geographic connection (one favourite is an ice-covered building, and the shocking news of how cold our winters are). But another reason is to serve as a kind of American design education ambassador, with the hopes that as I attend conferences stretching from Sydney to Belfast, global representation will populate our own national events, which fortunately, are held in English.

American design research culture will only be built from scratch once it acknowledges its international itch.

Footnotes

1. New Contexts / New Practices website.

2. Moldenhauer, J. (May 2010) Virtual Conferencing in Global Design Education: Dreams and Realities abstract. Global Interaction in Design, Visible Language 44.2. Guest editor: Audrey Grace Bennett.

Steven McCarthy is Professor of graphic design at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities campus. McCarthy has presented, published and exhibited in over a dozen countries.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues (including single copies of the latest issue). For a visual sample, see Eye before you buy on Issuu. Eye 79 is out any moment.